Claire Fontaine has just turned ten. Fulvia Carnevale and James Thornhill founded her in Paris in 2004: a ready-made artist with a name lifted from a pervasive French stationery brand. The duo has since acted as Claire Fontaine’s "artist assistants" as she has grappled with subjectivity under late capitalism. Heavily influenced by radical European politics of the late 60s and 70s, one of her central concepts over the years has been the ‘Human Strike’. Her most recent show at gallery T293 in Rome — built around the writings of 70s Italian feminist Carla Lonzi — is titled Pretend to be dead. The tactic of playing dead isn’t really so different from a strike insofar as it, temporarily at least, refuses/defuses one’s own use-value for those who would consume and profit from it. It’s not so different from Claire Fontaine herself, who in merely pretending to be alive simultaneously points to a particular kind of contemporary deadness.

Kyra Kordoski: You’ve been quoted as saying that Claire Fontaine emerged at least in part out of feelings of political impotence. This seems to be reflected pointedly in Stalemate, the chessboard frozen in a draw. Still, there is a duality, a sense of internal contest, or outright contradiction in many of the works in Pretend to be dead — the cheerfully painted defensive rotary spikes, the drain-pipe that alludes to a nursery rhyme while concealing a knife behind a trap door. Nothing falls on one political/ethical side or another, and there is a sense of being locked into a struggle that can’t be resolved throughout.

Claire Fontaine: Pretend to be dead takes place after many events and a pause of several months in exhibition-making for Claire Fontaine. The show certainly is a reflection on the ambivalences and the dead ends of adulthood (also conceived as a certain stage of one’s working process as an artist, a certain persistence of one’s presence within the art landscape). The feeling of political impotence is as much personal as immediately collective because it is precisely the poignant awareness of the lack of connection with others that could make life significant and powerful, it isn’t an individual problem, or it is individual because it is collective and vice versa.

The title of the show, Pretend to be dead, unconsciously refers to Musil’s Posthumous Papers of a Living Author; in the preface, he literally talks about ready-made poets and mentions the inevitable vulgarity of any estate, which is a memento mori for every artist.

KK: The paintings, in particular, set up an explicit tension between intimidation and supplication. On the one hand, there are the Fresh Monochromes with their anti-climb, never-drying paint, a product developed as a mechanism for controlling space—one ostensibly meant to deter theft. On the other hand, the Begging Paintings hold coins bound by magnetized canvases which (literally) exert fields of attraction, here aimed specifically at financial resources. It seems a metaphor for a dominant kind of art practice: artworks are puffed up as something almost ominously sacred (don’t dare touch the art) and presented at the same time as being in almost desperate need, demanding people’s money and attention. In an everyday sense, too, we constantly negotiate powerful messaging that tells us what we are restricted from and what we should be giving ourselves to.

CF: The analysis that you make here is very accurate; painting, in particular, is subjected to this tension: being something very reliant on its monetary value (that comes from elsewhere, and it’s not controllable by the artist) and at the same time bearing the highest ambition to be art in the most traditional sense of the term, detached from terrestrial worries, aspiring to the eternity and the sublime. There is in this exhibition also a temptation of falling into painting as a self-referential practice, something that escapes the labyrinthine layers of interpretation that conceptual art generates. Still, it is conjured by gestures that produce a distance from the merely retinal paint on canvas, the magnets, the paint that will never dry, and other things. Everybody is very lonely in front of these problems. Everybody finds individual solutions and remains silent on them; maybe this deafening silence will characterize our time in contemporary art in the future.

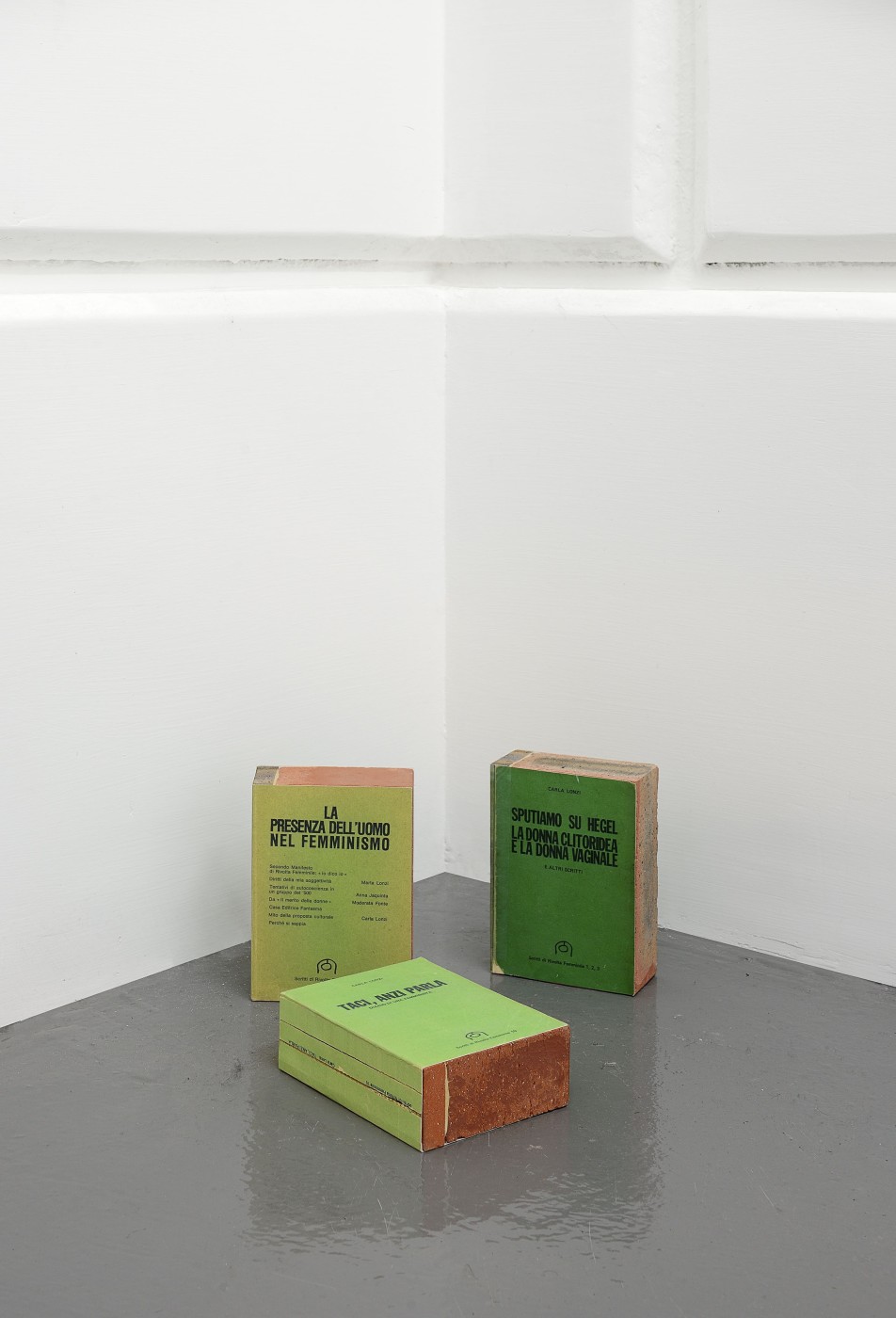

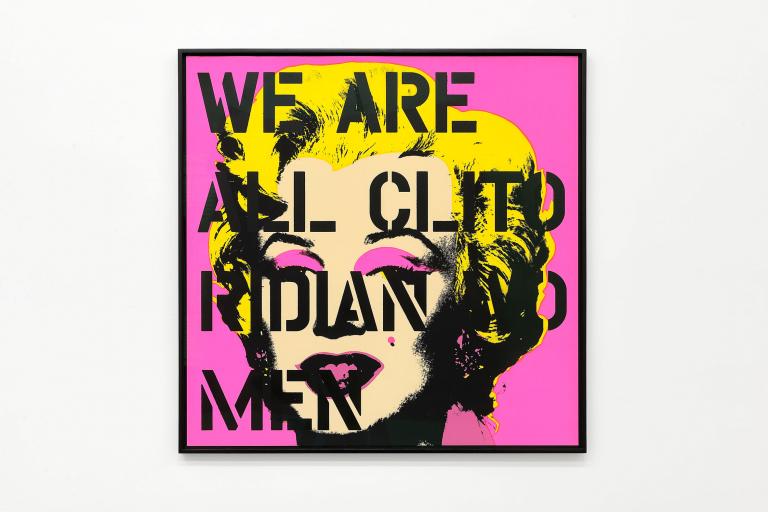

KK: The references to Carla Lonzi — the Marilyn Warhol bearing the slogan, “We are all clitoridian women”, the Brickbats wrapped in modified dust jackets of her books — are also references to a specific moment in the history of feminism, once that has since been contested on many fronts. In your e-flux essay on Carla Lonzi, you state:

…we must know that we ourselves are the result of a shameful but inevitable negotiation with patriarchy, with the Law, and with other forces that structure our lives. There is no longer any “good side of the barricade” because, in this perspective, there are no barricades. Our subjectivities themselves are the battlefield. Hence, the importance of embracing the double bind into which Lonzi’s work throws us.

Given that Lonzi’s writings are a starting point here, does this particular conception of doubly bound subjectivity in fact apply most appropriately to white women who are trying to negotiate intense personal relationships with figures of white heteropatriarchy (as lovers, husbands, fathers, brothers, etc.) to the exclusion of other experiences, or does it become an effective model for understanding the contested subjectivity of any consciousness, and if so, how?

CF: Lonzi’s complex legacy is a constant source of inspiration for us. The way she had of posing problems, clearing the field from parasitical worries, and looking for solutions that don’t exist yet and must be created from scratch is a model for thinking radically in general definitely. Although it has to be said that her reflection remains very specific to feminist problems, it cannot mechanically be transposed on other questions. We can also argue that feminism itself is a metaphor for a particular way to conceive conflicts and contradictions that don’t aspire to solve everything through dialectical schemes or the destruction of the enemy. This is the brilliance, for example, of Lonzi’s deconstruction of the Hegelian method in Let’s spit on Hegel: she can show how much the triadic way of thinking and the dialectics of the master and the slave are pure products of patriarchy, how conflicts have to be thought in a way that doesn’t annihilate the adversary and creates more space for everyone, more possibilities.