“I’m back and I’m going to speak my truth,” Yao Jui-Chung told me emphatically as he gave me a whirlwind tour of his sprawling retrospective, Republic of Cynic (2020 May 1–July 5) at Taipei’s C-LAB.

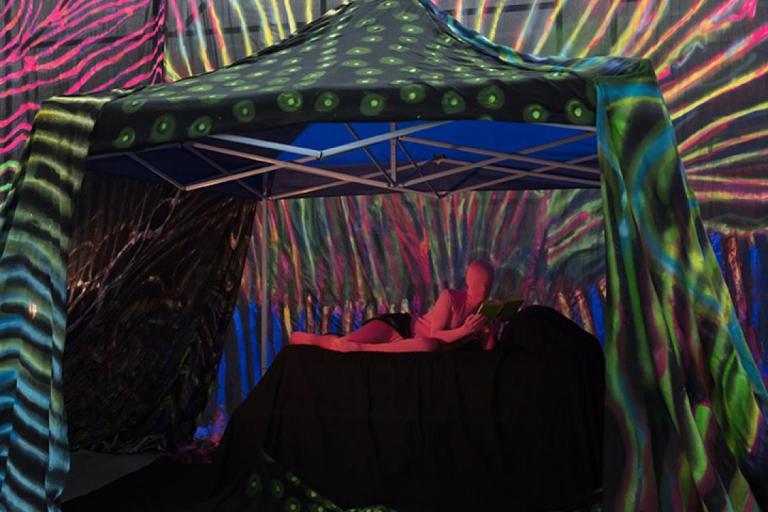

This was not the typical retrospective you might expect from one of Taiwan’s most famous and celebrated artists. The exhibition was not housed in the plush confines and hushed hues of the Taipei Fine Arts Museum, with its invincible aura of institutional and establishment clout. Rather, the presentation took place at C-LAB, in the US Aid Building and Chung-Cheng Hall of the former Air Force Command Headquarters.

Yao first visited the Headquarters as a young man when performing his compulsory military service. It would be difficult to think of a more appropriate setting for a meditation on nationalism, national identity, and the thorny issue of Taiwan’s geopolitical position.

Eschewing the tedium of a conventional retrospective, the exhibition had more the atmosphere of a live event. Exhibition-goers were presented with a passport from the artist’s fictional nation-state, which had to be stamped before entry. Such an act was made all the more poignant by the surrounding context: a global pandemic that precluded international travel.

Unable to cross physical borders, audiences could instead take a tour of Yao’s parasitic state within a state. Rather than functioning merely as an act of containment, the military structures enlivened the work, dissolving its boundaries. It was not clear where the artwork began or ended. Indeed, the boundaries between Yao’s life and art are just as fluid.

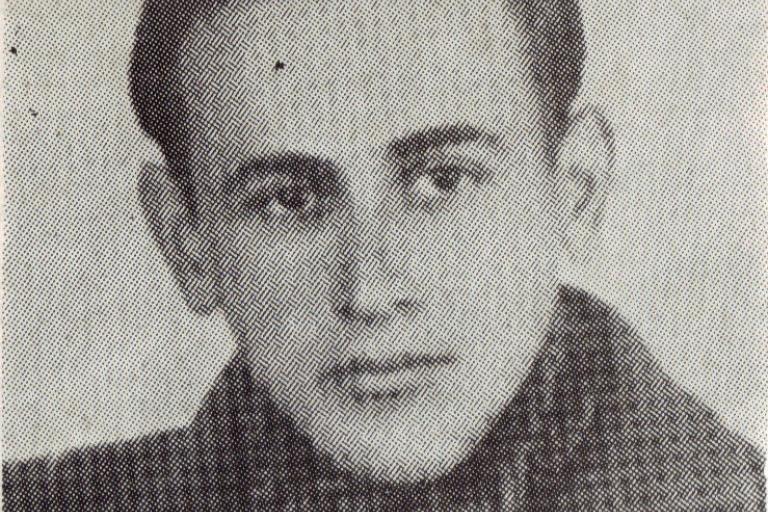

Yao came of age as an artist in Taiwan during a period of great turmoil and change on the island. He was eighteen in 1987 when the country ended 38 years of martial law and began transitioning into a democracy. It was at that time modern history’s longest period of military rule; a record since surpassed by Syria (1963–2011).

Taiwan is now arguably the most open and progressive country in Asia — the first in the region, in 2019, to legalize same-sex marriage. And it can be easy to forget that only a few decades ago it had been illegal to dance in Taiwan and that one could be jailed for thinking subversive thoughts. Yao was of the bridge generation that rode the wild waves of tumult and experienced freedoms unknown to the previous generation.

The title of Yao’s retrospective, Republic of Cynic, plays on Taiwan’s official name, the Republic of China (ROC). And the artist has reason to express cynicism, though the issues provoked through his constellation of poignant humour cannot be easily reduced. Yao is a master of the serious joke.

Taiwan’s convoluted history is ripe with parodic material. After losing China’s Civil War in 1949, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek and the nationalist Kuomintang (KMT) retreated to the island of Taiwan where they established their headquarters.

There, the Chiang regime ruled with an iron fist while trumpeting the dogma that the KMT would soon retake Mainland China from the “bandit” Communists. But as the years rolled on, the vastly diminished regime’s stance became increasingly absurd. Yao was of the last generation to be taught this policy in school.

For years, due to Cold War politics, Washington’s support helped preserve Chiang’s fiction. But in 1971, United Nations Resolution 2758 (XXVI) shifted recognition to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) as the only legitimate government of China, sending the ROC into the political wilderness.

Today, the ROC retains embassies in only a handful of peripheral countries, largely owing to Taipei’s “dollar diplomacy”. And most Taiwanese don’t identify with the country’s official name. There is a movement to change the name on Taiwanese passports from the “Republic of China” to “Taiwan”.

Yao’s father was among the Chinese Nationalists who, in 1949, retreated to Taiwan. Before fleeing the mainland, he had fought against the Japanese in the Second Sino–Japanese War, and started families with two previous wives. In Taiwan, he would start a law firm, become a city councilor in Taipei, and marry Yao’s mother, whose family has been in Taiwan for generations.

“Until he died, we didn’t know we were number three,” Yao told me when I probed into his life during an interview at his studio. “He was very old. I didn’t know much about him.”

Yao’s father died in New York, in 1989, while visiting a son from one of his earlier marriages. It was only after his death, through talking to older family members and reading news reports, that Yao began to piece together many of the details of his life.

His father was an ink painter of some renown. “He wanted to be a famous painter, but I think most Taiwanese have forgotten about him,” Yao says. “He had a lot of exhibitions of his paintings of flowers. My friends have collected some of his paintings and sold them to me. He had only left us with one painting… When I’d watch my father paint, I’d think, ‘So old fashioned!’” Yao says he believes his father would have approved of his success as an artist, though not his politics.

After martial law was lifted, an explosion of creative energy followed, as artists began experimenting with avant-garde forms and exploring previously taboo subjects. The subsequent years proved a golden period for the arts in Taiwan.

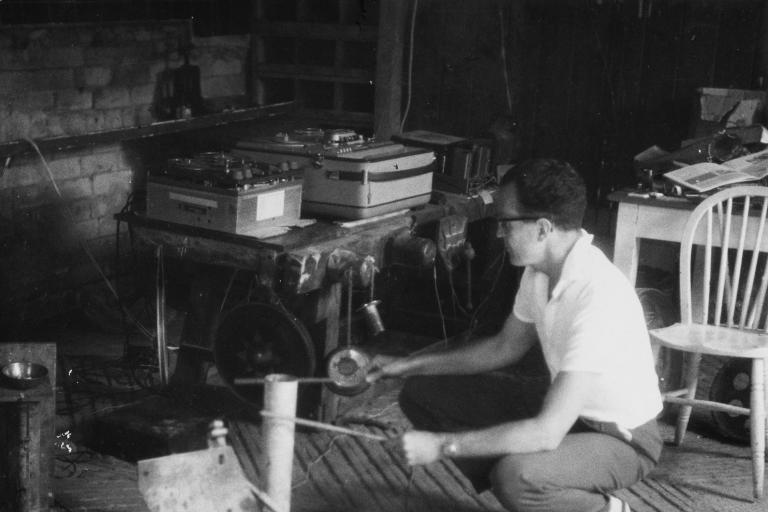

Yao attended the National Institute of Arts from 1990 to 1994. There, he produced expressionist paintings that his teachers thought too aggressive and avant-garde. In 1992, he co-founded the Ta-Da-Na Experimental Group and became involved in theatre and performance art.

It would be a jarring transition from art school to military service after graduation. Young men drew lots to determine their assignments, and Yao’s landed him in the Air Force.

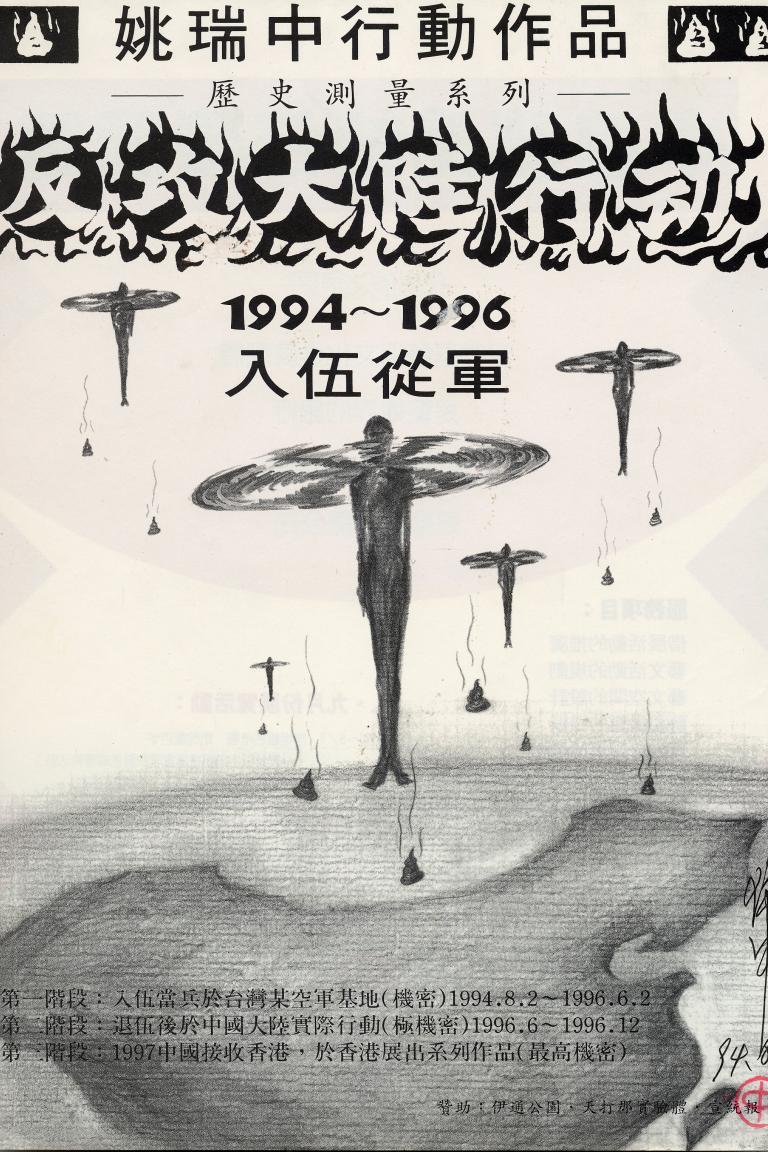

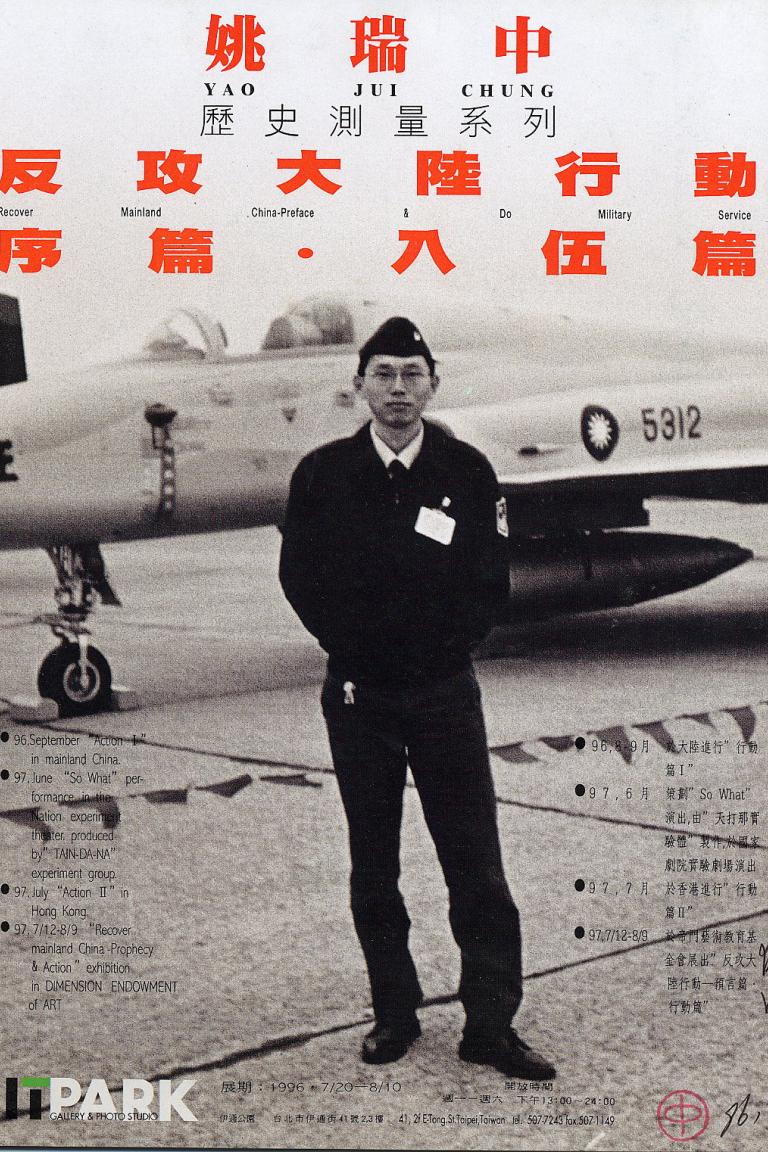

Upon entering the military, Yao purchased an ad in Hsiung Shih Art Monthly announcing that he was going to retake the mainland. This absurd statement, mimicking the long-running KMT policy, sat awkwardly in the climate of the time.

“People would think I was a lunatic,” he says. “Because at that moment, nobody wanted to talk about recovering Mainland China... So the people who wanted to unite with China would be angry. And the people who wanted independence would also be angry. I wanted to raise a sensitive political issue.”

After his father’s death and the lifting of martial law, Yao began to question his own identity and origins, and those of Taiwan. “I was looking for who I am,” he says. “I found that the ROC was a ghost, just as my father was a ghost. So I was trying to tell ghost stories.”

Yao had become completely disillusioned with the ROC and the notion of the nation-state. But ironically, upon entering the Air Force, he was placed in the Propaganda Department. “I was against any form of brainwashing,” he says, “even if I was part of the brainwashing machine — I was an operator.”

One of the requirements of soldiers was to learn by heart Sun Yat-Sen’s Three Principles of the People, the ideological basis of the KMT’s nationalistic political program. Soldiers would write essays based on the text, and Yao would determine whether one’s essay was ideologically sufficient for him to be granted leave. Yao was also responsible for inspecting soldiers’ incoming and outgoing mail for any leaks, subversive thoughts, or signs of strife among the rank and file.

“Some soldiers, if they had problems with their girlfriends, they would commit suicide,” Yao says. “So we had to check their letters. If his girlfriend would say, ‘Bye-bye, see you in the next life,’ we would tell him to come in and talk to the second lieutenant. And he would say, ‘Don’t be sad. Come to work. If you’re good, you can go to karaoke.’”

At night, Yao was in charge of running the karaoke room. He would put on records requested by soldiers and cook barbecue, dumpling soup, and chicken legs. “Because the soldiers needed to relax, I collected all different kinds of comics, and I would play art movies — but most of them, they didn’t understand. I played some very terrible films, such as 120 Days of Sodom.”

Yao’s second year in the Air Force coincided with the beginning of the Third Taiwan Strait Crisis (1995–1996), when China fired missiles into the Taiwan Strait and simulated an amphibian invasion. The PRC was angered by the statements and policies of Lee Tung-Hui, the first native Taiwanese leader of the ROC, who they viewed as a separatist determined to split the “motherland”.

Lee had been sworn in as president in 1988 upon the death of Chiang Kai-Shek’s son, Chiang Ching-Kuo. He accelerated the process of democratization that had begun under the previous president. Lee encouraged the building of a Taiwanese identity, and enraged China by insisting on state-to-state diplomatic relations.

In 1996, Lee won a second term in Taiwan’s first-ever direct presidential election. Shortly before the election, China again sent missiles into the Strait intended to intimidate Taiwanese into not voting for Lee, but its threats only made him more popular. He won easily. In 2001, Lee would be expelled from the KMT, of which he had been Chairman, and go on to explicitly call for Taiwanese independence.

“He was the biggest spy in Taiwan's history,” Yao says. “He fought with the old men in the KMT… In 1996, China sent three missiles across the strait. I was in the army, so every night we were sleeping with guns and gas masks, for a whole month without leave. We would hide in the jungle. For one week, we perched on top of an aircraft hangar waiting to shoot parachutists out of the sky.”

Within weeks of completing his military service, in June 1996, Yao held a solo exhibition, Recover Mainland China — Preface & Do Military Service, at IT Park, a private gallery in Taipei. The exhibition featured military documents Yao had secretly collected during his service.

“I invited my boss from the army. He was the highest leader in the Propaganda Department. I showed all the papers he had signed. I could tell he felt very uncomfortable. We didn’t have any contact after that.” Years earlier, Yao would have likely been jailed for such actions, but the social and political climate under Lee Tung-Hui had radically shifted.

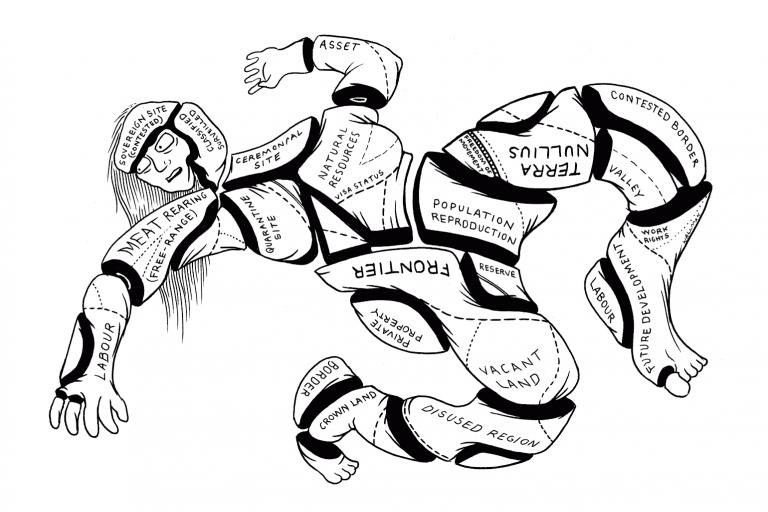

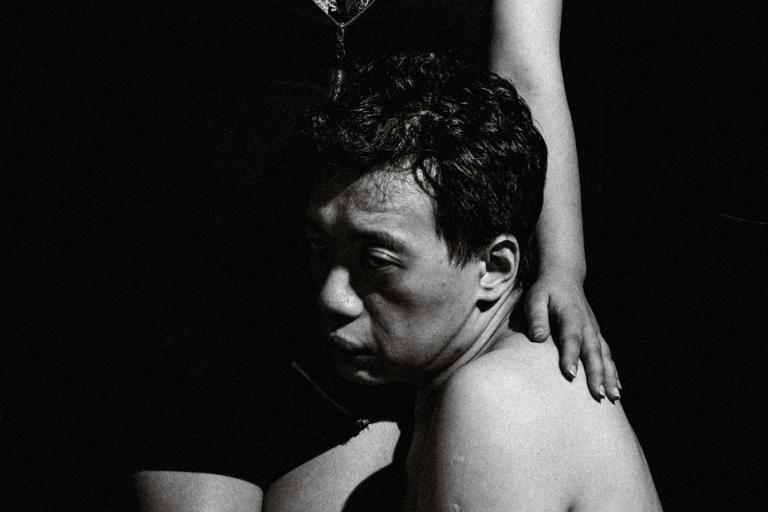

In 1997, Yao represented Taiwan at the 47th Venice Biennale in the exhibition Taiwan Taiwan: Facing Faces. He exhibited his photographic installation Territory Takeover (1994), which he created shortly before his military service.

In producing this work, the artist traveled to six historic locations, each a landing spot of Taiwan’s successive colonial incursions — from the Dutch and Spanish to the Japanese and various waves of Chinese. At each location, Yao stripped naked and photographed himself urinating like a dog reclaiming its territory. The photographs are sepia-toned and produce a faux historical effect, each image presented within a gaudy golden Western frame and exhibited alongside a gold-painted toilet.

The 1990s marked a period of “Taiwanization”. Before then, schools only taught Chinese history up to the 1949 takeover by Mao Zedong and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The government did not allow Taiwanese history in the school curriculum. Now, decades of pent-up energy had been released, and the desire to break from the ROC and the ghosts of the past was palpable.

But while Yao actively called for the building of a new Taiwanese identity and challenged artists of his generation to develop new aesthetics, the essentializing nature of much of the new Taiwanization discourse didn’t sit well with him. “They were talking about who was a ‘real’ Taiwanese person. I wanted to use this work to say that there is no real Taiwanese person.”

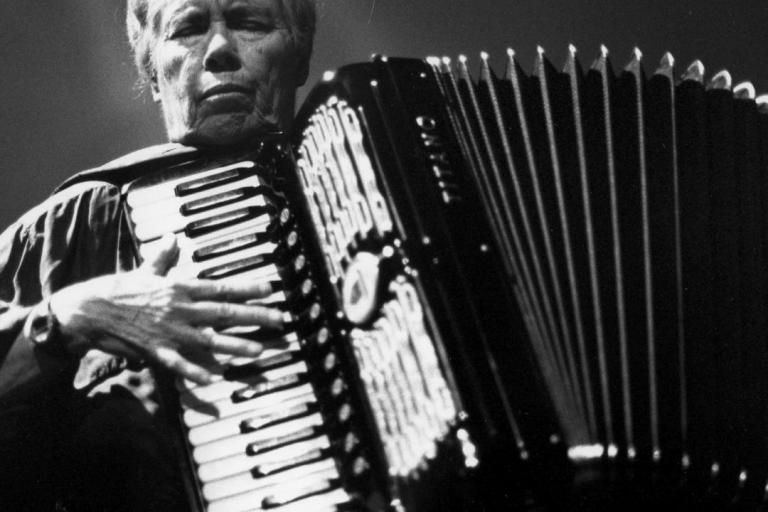

The older generation of Taiwanese artists, who had grown up with a clear enemy in a more straightforward oppositional environment, tended to be more solemn in their pronouncements. Some didn’t appreciate Yao’s antics.

“They didn’t think Taiwanese history should become a joke,” Yao says. “But for me, why not? They just copied their art from Western styles. It was old-fashioned Impressionism. And it was third-hand, because the Japanese copied it from Europe, and we copied it from the Japanese.”

In 1996, Yao made his first-ever trip to China, where he felt little connection to the birthplace of his father and could detect barely a trace of the ancient culture lauded in his high school textbooks.

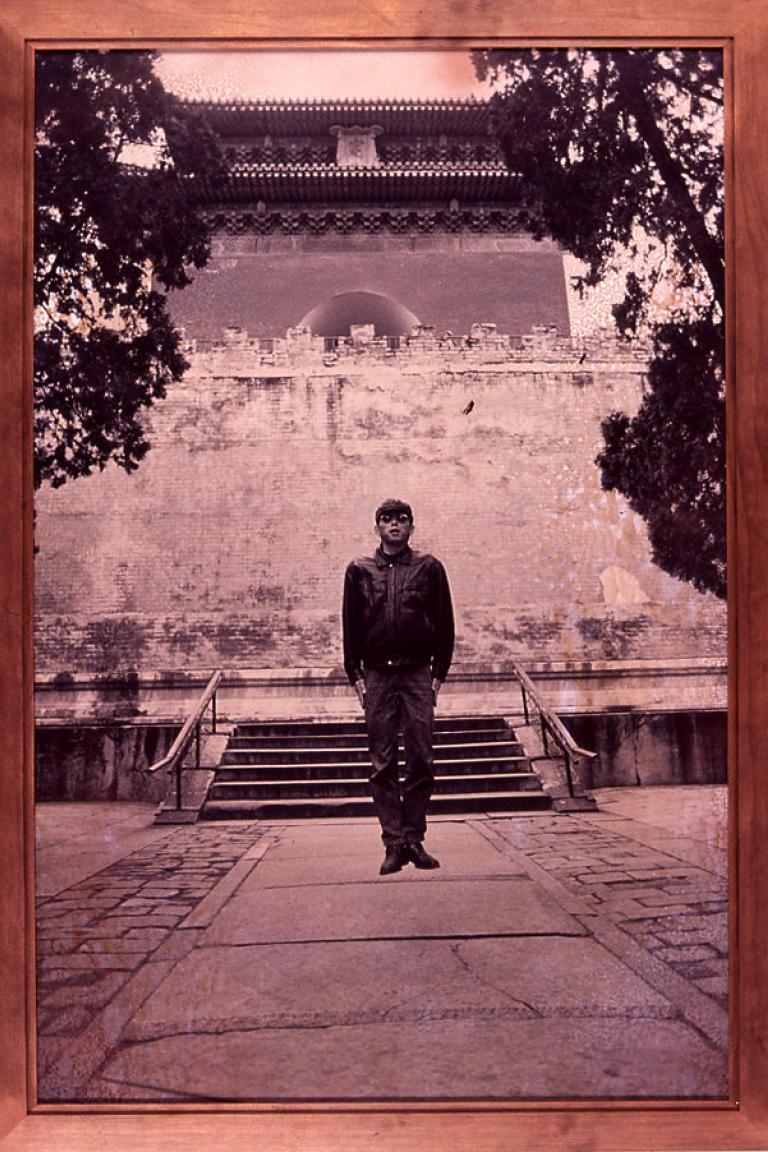

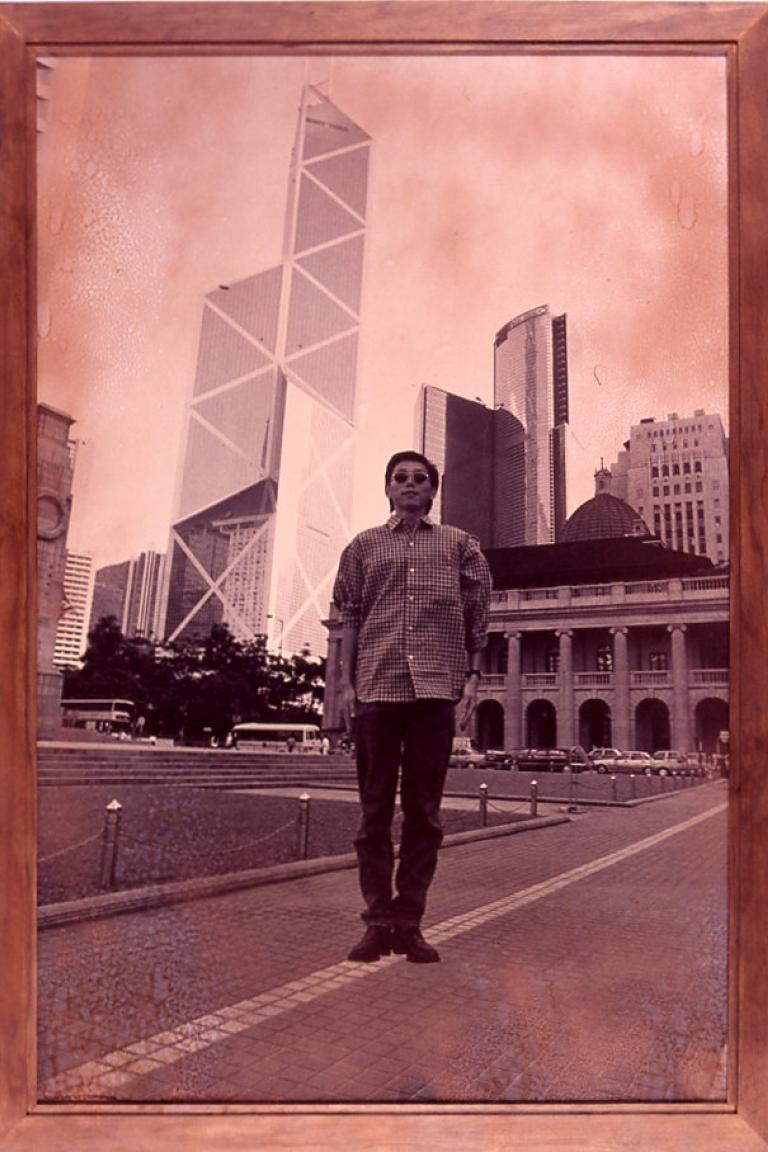

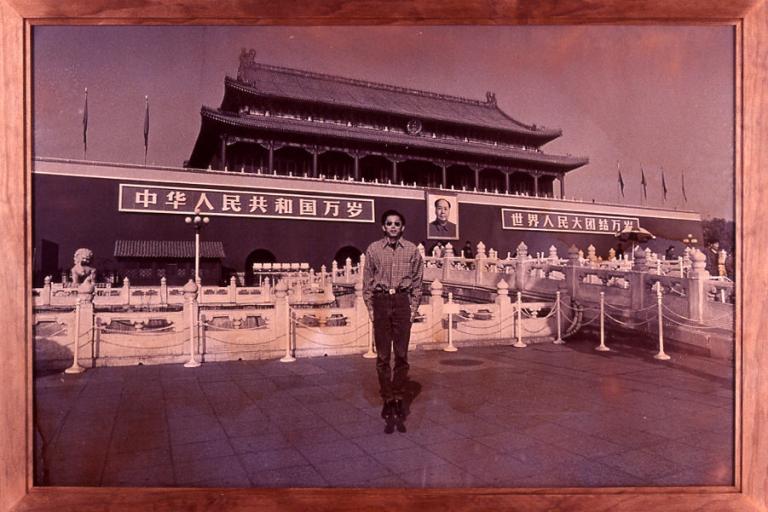

During this visit, he created the photographic work Recover Mainland China — Action. Yao had himself photographed in front of famous Chinese landmarks, including Tiananmen Square, the Great Wall of China, and the National Museum of China, the latter of which displayed a giant clock counting down the minutes until the handover of Hong Kong.

Here we see the artist as a one-man army ready to carry out the ROC policy of recapturing the mainland. The artist appears to levitate off the ground. “I’m pretending to be a tourist,” Yao says. “But actually, I’m a spy. I’m in China, but my feet never touch the ground.” Art critic JJ Shih described Yao as appearing “phantom-like or rigid… a fanatical follower of the slogan”.

The floating effect is convincing. In 2001, the Taipei Times erroneously reported that the artist had superimposed his image against the landmarks. “It was very difficult to take these photos,” Yao says. “I jumped: One, two, three! Then I escaped running away.

"My sister took the photos. When I was at the karaoke in the Air Force, I would practice every night. We had a large mirror, so I was always jumping and learning.” Each time he was chased by security but got away; tales of his daring escapes now appear as a quaint reminder of a less menacing time.

“At the time, when I did Recover Mainland China – Action, China was very open,” Yao says. “They welcomed everything from the world, all different corners… They were very curious about Taiwan.

“But they didn’t understand Taiwan at all. They thought Taiwanese people were very poor and that they ate tree roots and banana skins. Because when they were children, their government said, ‘We need to save the Taiwanese people because they are very pitiful.’”

In 2005, Yao was invited to give a talk about Taiwanese performance art at the China Academy of Art in Hangzhou. At the airport, customs officials searched his luggage and discovered one of his Recover Mainland China works. They pulled him into a small room and demanded an explanation.

Surrounded by six officials, Yao explained that this was “art” and that he was there on invitation to give a talk. But when he attempted to call the academy to provide clarification, no one answered. The officials began playing the artist’s DVDs, becoming more concerned and perplexed. Yao ended up giving them a two-hour lecture on performance art until they finally let him go. At the Academy, Yao spoke to 600 students.

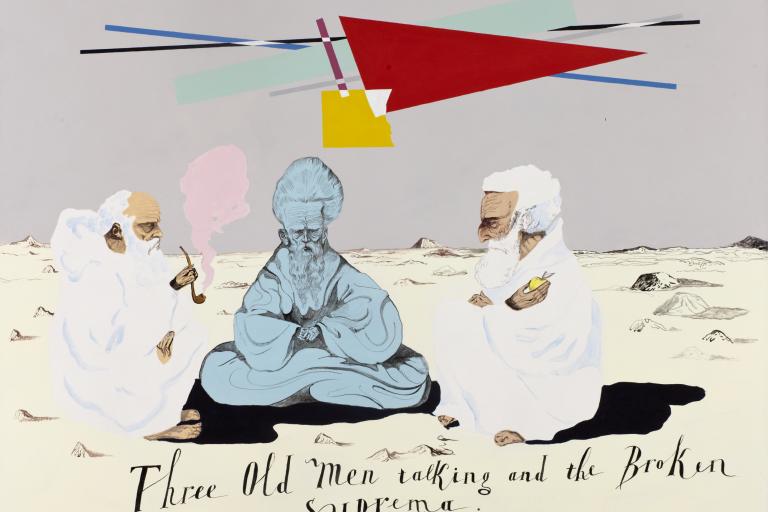

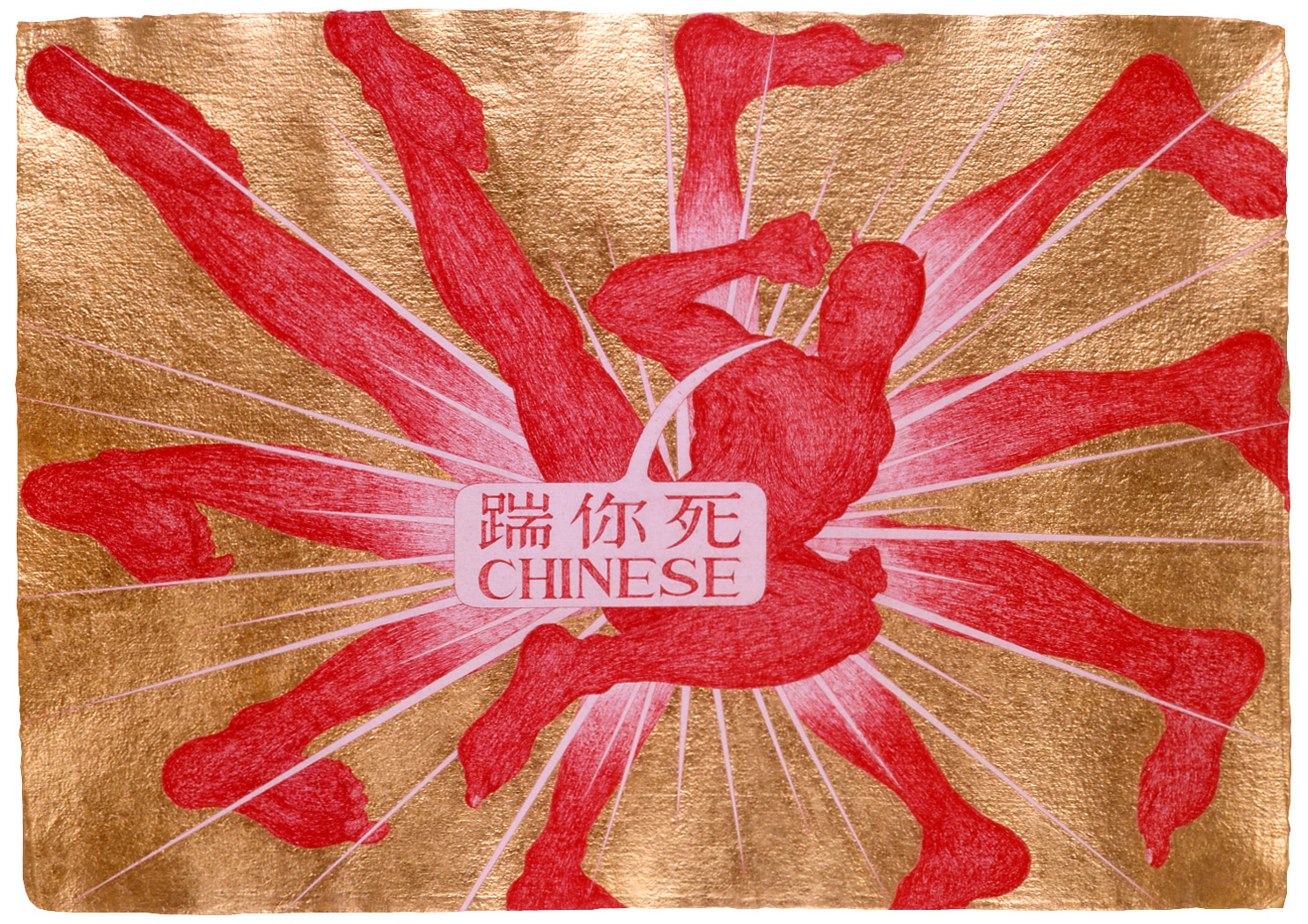

In 2007, Yao was invited to exhibit at the Shanghai Art Fair. He exhibited a piece from his Cynic Republic series (2003-2006), a painting of a horned red demon character kicking in all directions, with the word “Chinese” in English and a Chinese transliteration meaning “kick you to death” (踹你死 (chuài nĭ sǐ). The painting was removed without explanation on the first day of the fair. Yao no longer exhibits in China.

He also experienced trouble in Taiwan in 2011 when another painting from this series was exhibited outside Taipei’s Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA). In this painting, the demon character is seen copulating with a green, dog-headed female character. Here, the English word “Taiwan” is transliterated into Chinese characters meaning “he plays, you die” (他玩你死 tā wán nǐ sǐ).

The painting appears to reference the constant threats issued by China and the futility of cross-strait dialogue. But Yao has also referred to it more broadly as representing authority in relation to a silent, passive public.

When the painting was exhibited outside MOCA, it created an outcry. Taipei City Councilor Wang Shih-Chien alleged that the painting insinuated Taiwanese people were being raped, and while he supports artistic freedom, it was unacceptable for artists to display derogatory or self-defamatory work.

The controversy was resolved when the painting was moved inside the museum’s plaza and later to a discreet location within the building. Speaking to the Taipei Times, Yao said, “I thought this was something that only happened in authoritarian countries.”

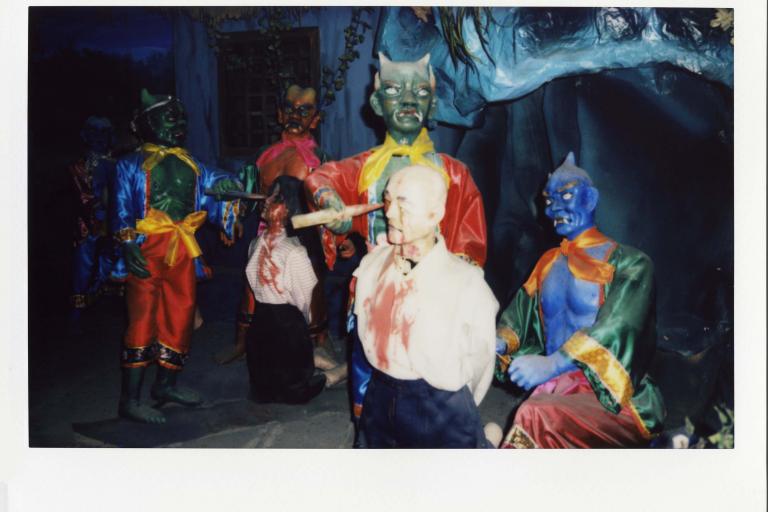

One of the highlights of Yao’s Republic Of Cynic retrospective is the screening of his short film Long Live (2011-2012). The film is presented in the auditorium of Chung-Cheng Hall, notably built to memorialize Chiang Kai-Shek after his passing in 1975. Yao shot the film on the centenary of the Xinhai Revolution and the founding of the Republic of China.

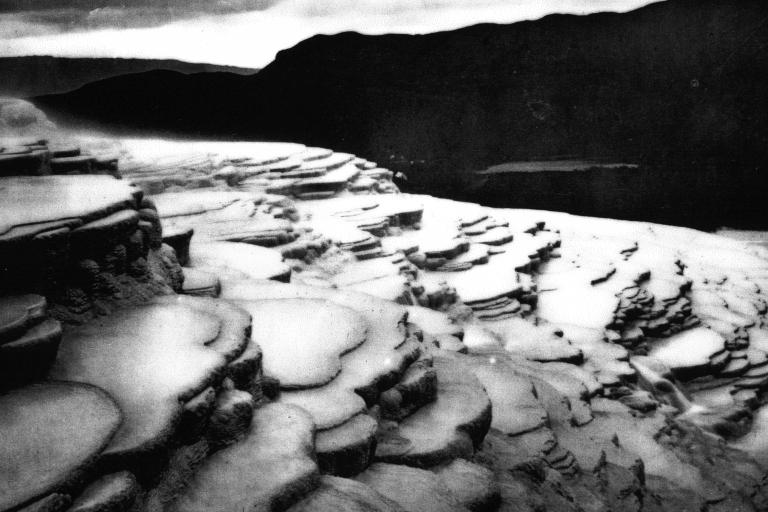

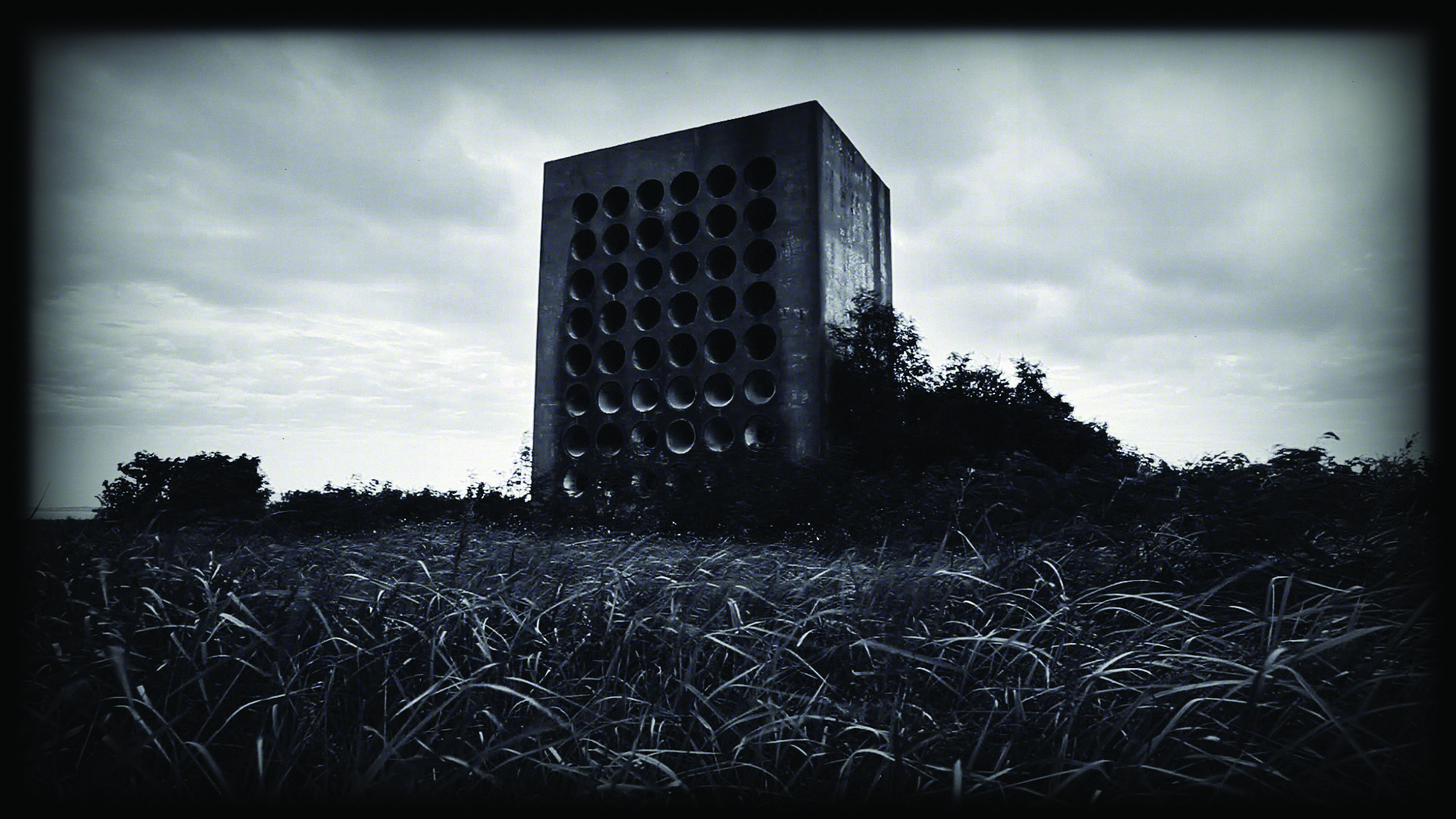

The film begins on the gloomy desolate shores of Kinmen Island, a frontier of the Cold War located just six kilometers off the coast of China. There, Chiang’s Nationalists repelled an attack from Mao’s Communists shortly after retreating to Taiwan.

Kinmen became a stronghold for the ROC and withstood repeated bombings by the CCP from the late 1950s through to the late 1970s. On the northwestern tip of the island stands a 30-foot tall concrete speaker, the Beishan Broadcasting Wall, which would blare ROC propaganda into the mainland with messages such as, “Our steamed buns are bigger than your pillows!”

In an eerie dream-like state, Yao’s camera caresses the shore of the heavily militarized island, allowing our eyes to scan the bomb shelters and tanks dotted along the coast, facing outward towards the enemy. The facilities are ravaged by decay and have gradually been conquered by enveloping foliage, as nature reasserts its dominance over the eternal empire.

Suddenly, a piercing air siren starts up and our eyes wander down the narrow halls of an underground bunker. Then, out through the giant speaker blasts a lone repeated phrase: “Wan Sui!” (“long live”, literally “ten thousand years”).

The voice projected by the speaker belongs to the Generalissimo, played by Yao, who is standing on stage in the derelict Jieh-Shou Hall on Yangmingshan Mountain. Behind him is a faded and partially concealed ROC flag, but the grand hall is a tattered ruin.

Debris hangs from the ceiling like vines. Fragments peeled off from the walls are strewn about the floor. The hall is empty but for the Generalissimo, who, locked into his rhythm, right fist pumped into the air, repeats his shrill call for the long life of the regime, which has been reduced to an empty shell.

The camera pulls back, and we realize we are witnessing the scene on a screen in an empty movie theatre. Light streams in through two open doors revealing a blizzard of dust. We contemplate momentarily the stillness of the space frozen in time and the emptiness of the illusion stripped bare as the curtain is pulled back. Then the doors are shut. The lights go out. The show is over.

Yao created four newly commissioned video works for the retrospective. Each deals with a historical moment that impacted Taiwanese perceptions and the island’s relation to the world. These events include the moon landing of 1969, the September 11 attacks in 2001, and the massive 1979 protests in Taipei against the US after Washington severed formal relations with the island.

But the boldest work is undoubtedly “Tank Man” (2020), a recreation of the iconic moment of resistance from the bloody Tiananmen Square massacre of 1989. To produce this work, Yao ordered inflatable plastic tanks from a factory in China, upon which he emblazoned the Republic of Cynic emblem. These tanks are usually sold to African dictators who use them to trick satellite surveillance into overestimating the size of their military force.

“China is the biggest factory in the world,” Yao says, “ so they’ll produce anything. We found there’s a company that produces this weapon. So we asked them to produce four tanks. They didn’t know about Tiananmen Square. They didn’t know about the Tank Man. We told them we’re from the military and that we were organizing a big celebration.”

The sagging tanks sat outside the exhibition like partially deflated Oldenburgs. In the video, Yao’s Tank Man stares them down, armed with two plastic grocery bags. Like the original Tank Man, he tries to wave the tanks away, then climbs on top of the turret of one and attempts to negotiate with the driver.

But in Yao’s recreation of the story, instead of being dragged away by the authorities, the Tank Man utilizes superhuman strength to push the lead tank back and out of the frame.

“After this work, I’ll never go back to China,” Yao says. “I won’t go to Hong Kong either. I don’t care, because I’m very old. It doesn’t matter.”

It has been common in contemporary art of the current era of neoliberal globalization to view history and instances of the authoritarian past with a level of detached irony. But now this order is itself coming under strain. The ghosts of the past swirl above us and the concerns of Yao Jui-Chung’s body of work suddenly feel more urgent.

As I wandered through the former Air Force buildings fixated upon Yao’s excavation of propaganda organs of the past, I wondered how the future would contemplate our era. Will the ghosts of authoritarianism have the last laugh? I was left with a feeling of transitoriness and reminded of another of Yao’s favourite phrases: “Everything will fall into ruin.”