The following is an extended excerpt from a new 30-page article about the Art Ensemble of Chicago by Kurt Gottschalk. The full feature runs in the new print issue of Taiwan arts magazine White Fungus. The feature is the result of several decades of research by the author and includes interviews with members of the group and rare photographs. You can purchase the new issue of White Fungus here.

But revolutionaries aren’t often revolutionary for long. They tend to claim some piece of turf and then protect it. What’s revolutionary about the Art Ensemble of Chicago is that, for more than fifty years, with members lost and as styles changed, they have continued to seek new ground. And in its 50th year, the band tripled in size and put out a record that challenged its own tradition. A revolutionary who’s unwilling to change won’t likely be revolutionary for long.

ANCIENT

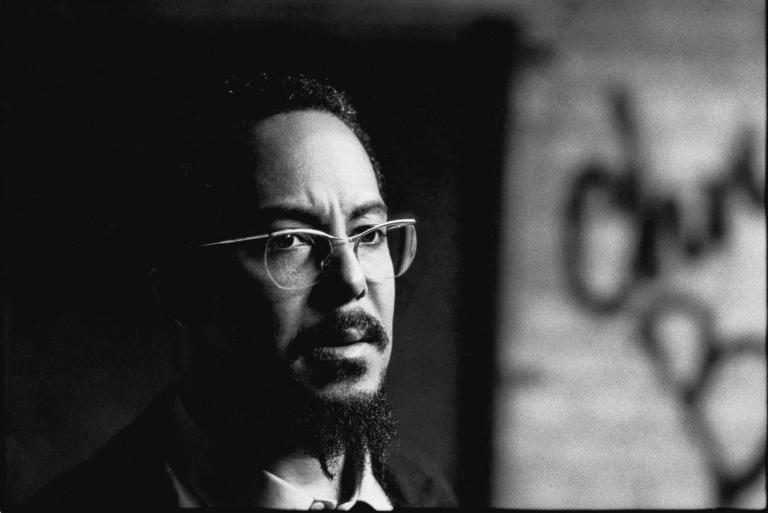

I met Lester Bowie only once. It was at an afterparty following the final night of the 1992 Chicago Jazz Festival, where Bowie’s Brass Fantasy had headlined. It’s an unremarkable story and an unforgettable moment — at least for me. For the exemplary showman, masterful trumpeter, and focal point of legendary jazz innovators the Art Ensemble of Chicago, it was a momentary intrusion he’d likely forgotten as soon as it was over.

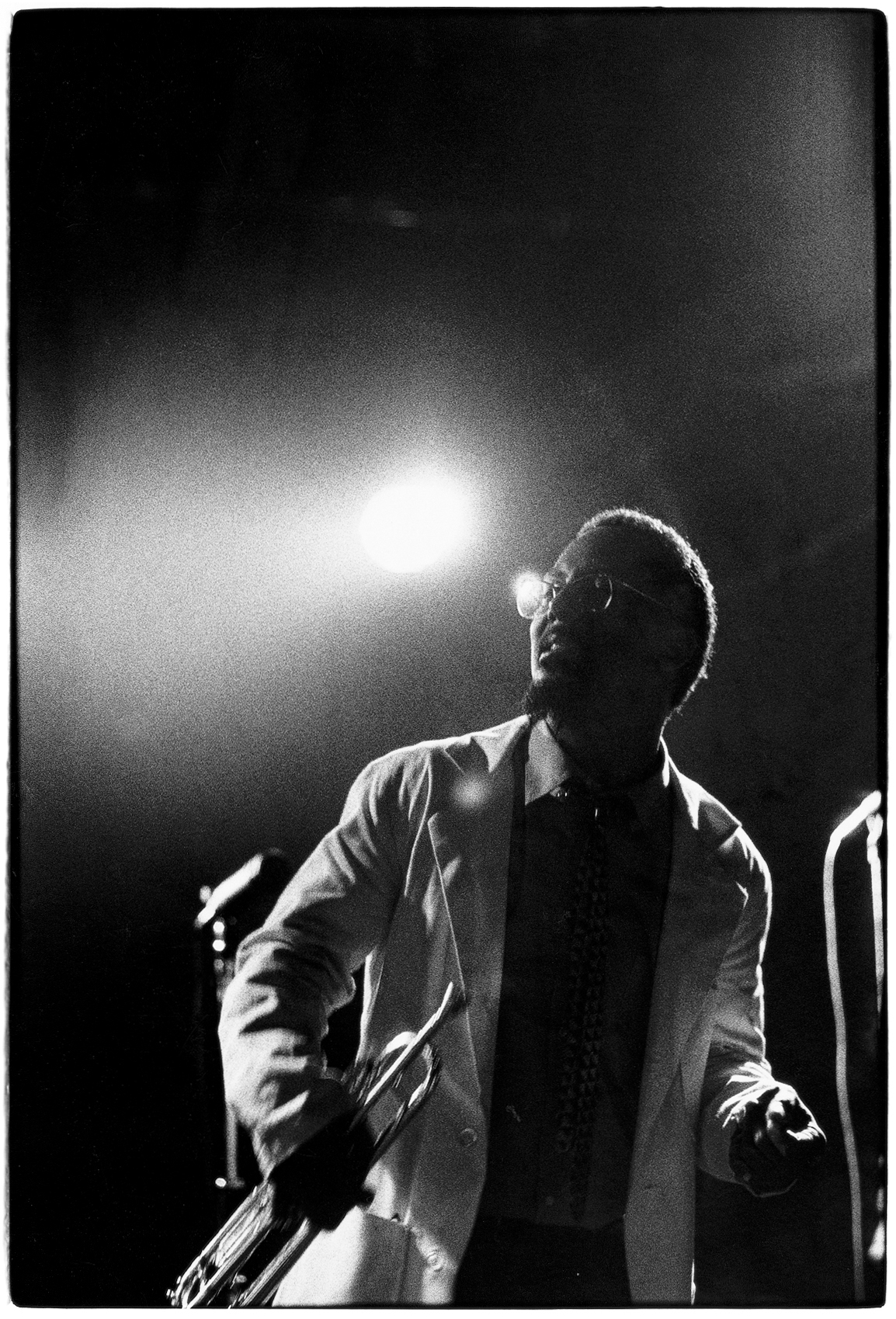

Bowie was an absolute entertainer who brought to the Art Ensemble not only remarkable acumen as a musician but the notion of putting on a show, a sensibility that had largely been disposed of by the serious high-mindedness of such musicians as Miles Davis and John Coltrane. Bowie’s Brass Fantasy was essentially a side project, but it was his forum — a reverie of glitz, glamour, and style, seducing audiences with jazz takes on popular hits (something else that fell out of favour with the avant-garde cognoscenti of the 1960s) while escorting them into unfamiliar sonic realms. Bowie put out eight records with the Brass Fantasy between 1985 and 1998, easily the best two of which are live recordings. The band, and Bowie, loved the stage.

At Chicago’s Petrillo Music Shell that summer night, the breeze off Lake Michigan cooling the sticky air alongside Lake Shore Drive, the Brass Fantasy concluded a remarkable triple-header with Jaki Byard (known to me at the time for his tenure in Charles Mingus’s band) playing a solo set of simultaneous piano and saxophone, and Randy Weston performing music from his album The Spirits of Our Ancestors. (Like Bowie, Byard and Weston no longer walk among us; this story will be possessed with passing spirits.) The Brass Fantasy in all its glory — four trumpets, two trombones, French horn, tuba, and a pair of drummers (including Art Ensemble ‘sun percussionist’ Famoudou Don Moye), no reeds, no keys, no bass viol — played interpretations of songs made famous by Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Michael Jackson, and the Platters, along with some of Bowie’s tunes. At midpoint, during their take on Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit,” Bowie leaned back on his heels, reached inside his jacket, pulled out a gun, and fired a blank into the air. It wasn’t just a show-stopper. It was a breath-stopper. My young mind was duly impressed.

Costuming was a key part of the presentation for both the Art Ensemble and the Brass Fantasy, and Bowie’s simple costume was the same for each: a lab coat over his street clothes. It marked him as an experimenter with the precision of a surgeon and the abandon of a mad scientist. For the Jazz Festival set, the rest of the Brass Fantasy walked out wearing matching blue lamé lab coats, followed after a fashionable moment by the leader in silver lamé, and they launched into “Night Time Is the Right Time.” As a set opener, the song packed no small punch. We were all there, that night, at the right place. It’s a warmly familiar song, a feel-good party tune. But it also speaks to a deep philosophy that runs through all of Bowie’s work. The genre isn’t jazz or blues or R’n’B or soul. It is, as Bowie termed it, “Great Black Music.”

“Night Time Is the Right Time” was recorded by Big Bill Broonzy and Roosevelt Sykes in the 1930s, Ray Charles in the 1950s, Aretha Franklin in the 1960s, Tina Turner in the 1970s, and James Brown in the 1980s. In 1985, Bill Cosby and his TV family lip-synched to the song in an episode TV Guide later named in its “Greatest Episodes of All Time” list; six seasons later, Bowie provided the recording of The Cosby Show opening theme. (Brass Fantasy’s own version of “Night Time” appears on the album The Fire This Time, recorded at a concert in Switzerland four months before the Chicago Jazz Festival appearance and the best commercial document of the mighty band at work.) For the encore, the musicians appeared outfitted in silver lamé, Bowie now in gold, and played an upbeat march with a fast-paced group chant that included the repeated refrain, “Brass Fantasy number one / Pump up the rhythm.” You don’t represent the lineage of Great Black Music with undue modesty.

“Great Black Music” is capitalized. It’s what Bowie played and the statement he made, from the early 1960s recordings with his wife, the R’n’B singer Fontella Bass, until his death in 1999. Bowie coined a motto for the Art Ensemble, one which would also be adopted by Chicago’s Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), the organization out of which the Art Ensemble was born: “Great Black Music, Ancient to the Future.” It wasn’t about musical style. It was about race and history. It was a movement.

That night back in 1992, at the Southend Musicworks afterhours jam, which followed every night of the Jazz Festival, I spotted Bowie across the crowded room wearing seersucker with a straw hat and smoking a cigar. Forcing my way through the crowd and through my shyness, I went over to him and told him how much that gunshot had stunned me, hoping to demonstrate that I wasn’t an altogether unaware white boy. He grinned broadly and said, “Oh, you liked that, did you?” I said something in response, I would guess, and soon his attention directed itself elsewhere, with me left thinking that he knew more about what I didn’t know about the world than did I.

The party was packed, and Bowie was one of the guests of honour, but he was, or at least seemed (if only momentarily), approachable. And if this story has a point, this long story I’m asking you to embark on with me, it’s just that. Lester Bowie, and with him the Art Ensemble of Chicago, made experimental jazz approachable and, at the same time, gave jazz snobs permission to like Michael Jackson. He leveled the playing field, and he smiled while doing it.

I was a recent convert to jazz at the time, having moved to Chicago with a small collection of records by Coltrane and Mingus, David Murray and Henry Threadgill — and by virtue of the AACM had discovered jazz as a live medium. In no small part due to Bowie’s charisma, the Art Ensemble was an early favourite of mine, and has been ever since. The Art Ensemble was initially organized in 1966 as a small group with fluid membership under the name the Roscoe Mitchell Art Ensemble. The quartet of two saxophonists, Mitchell and Joseph Jarman, bassist Malachi Favors Maghoustut, and Bowie relocated to Paris where, in 1969, they met up with American drummer Don Moye, who grounded the group and made them a band. His solid foundation and African drums solidified both the sound and image of the group. It doesn’t diminish their musical brilliance to note their marketing nous. They were intriguing and immediately identifiable — a posse of mystic warriors, self-styled “urban bushmen” with a street-savvy smooth, and a mad scientist among their ranks.

They were, in their prime, in their first prime (their primary prime), a band so tight they didn’t need to be tight. In the midst of an extended, open-form improvisation, any one of them could play a phrase, and they all knew where they were on the map. They would shift on a dime, or not shift. Two, three, four of them would answer the call to delve into chant, or Dixie, or hard bop, or an art song so odd it’s equally uncategorizable and unforgettable, a truly remarkable feat. (Hear Mitchell’s early song “A Jackson In Your House,” written during the band’s French sojourn about the cat he’d left behind in Chicago, as evidence of the uncategorizable unforgettable.)

By the time I got to Chicago, the Art Ensemble had long since gone global. Bowie and saxophonist Joseph Jarman had relocated to New York; Mitchell had moved to Madison, Wisconsin. Moye was still in Chicago, but he didn’t play there; years later, he told me no one in town paid him enough to perform. The only member I got to see play regularly was the shamanistic bassist Malachi Favors Maghoustut. As a fanboy for whom the descriptor ‘aspiring journalist’ would have been grandiose, Favors was as unapproachable as Bowie was inviting. He seemed ancient, wise, sphinx-like even, and a little bit scary.

I moved to New York City in 1993 and, on Thanksgiving night in 1994, I saw the Art Ensemble for the first time, in a rare appearance at the Knitting Factory in lower Manhattan. Before they took the stage, whispers moved through the room that Jarman wasn’t there, that he wouldn’t be playing that night. I later learned that he’d left the band, marking the first lineup change in some twenty-five years. In those pre-internet days, I made the Jarman mystery my mission. I wanted to know why he had left the greatest band in the world. Asking around, I eventually learned he operated a dojo in Brooklyn (just a couple miles from my apartment, in fact) where he taught aikido and occasionally performed. I dropped by one Saturday, and there he was. His focus was on martial arts now, he told me, and when he made music, he did so with people in his dojo. We visited for a while. I found I didn’t have so many questions for him after all.

Nine years after that, I visited the Jikishinkan Aikido Dojo again, this time with the mettle of a journalist writing for All About Jazz–New York. He had rejoined the band; although by that point, Bowie was no longer alive. “In January, I started again,” Jarman said, speaking in a plain, calm, articulated voice. “It was a great decision, because I loved the Art Ensemble and missed it. We had always been in communication. Even Lester, he was always saying, ‘Come on back.’ His transition was really the core. They were just a trio, and it was nice to be a quartet again.”

To read the rest of the article you can purchase a copy of White Fungus issue 17 here.