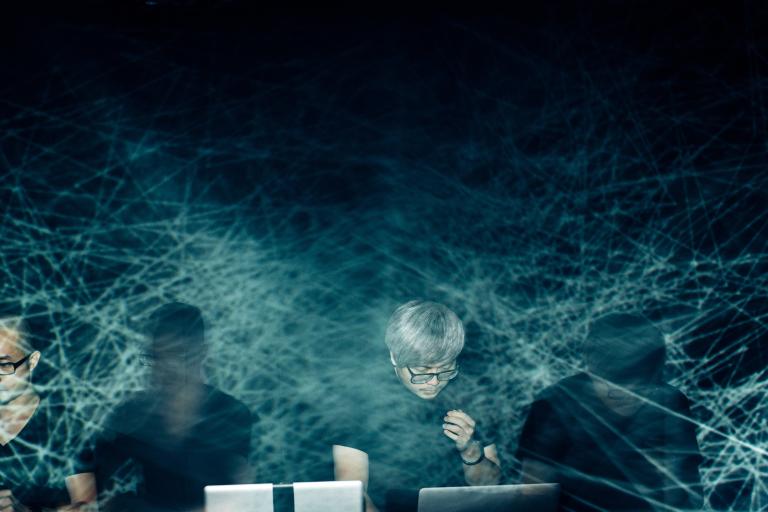

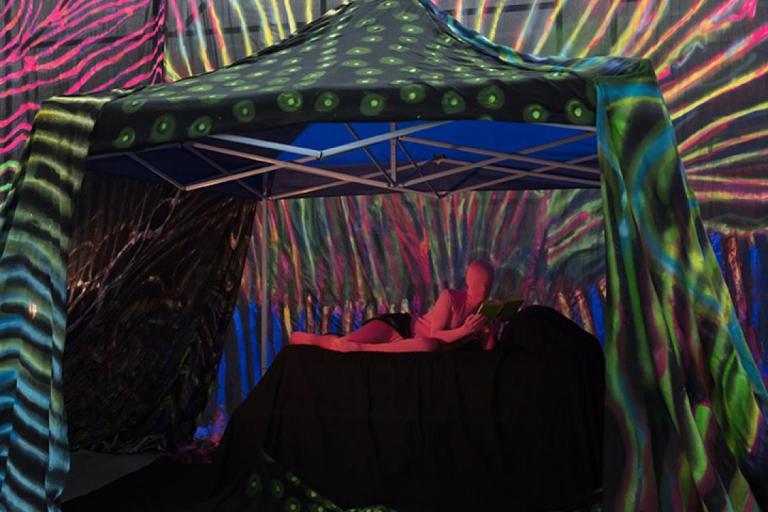

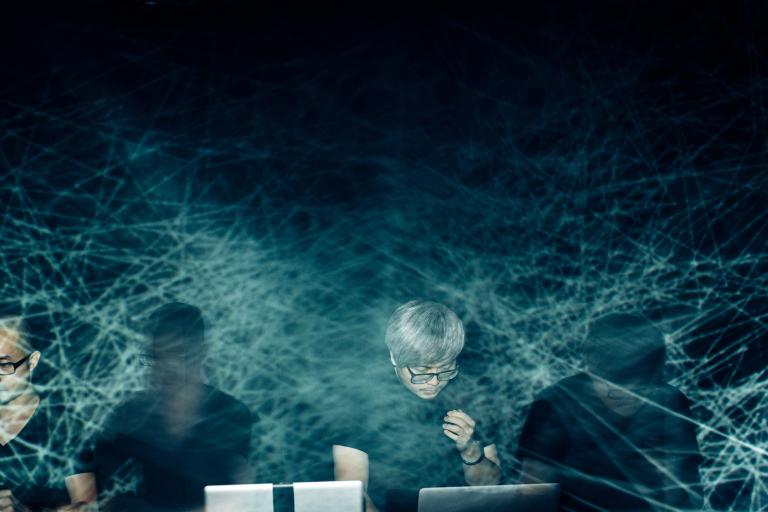

While Kari Altmann’s work is usually filed under ‘post-internet’, she prefers terms like ‘hypergenre’, ‘post algorithmic’, ‘ambiguationist’, ‘cloud-based’, ‘swarm-based’, ‘file-based’, or ‘nutribal’. ‘Post-internet’ is the somehow increasingly used but still largely unsatisfying place-holder-y term for art that engages either formally or conceptually with digital communications culture (known, often, simply as ‘culture’). Following on the heels of ‘net art’—90s work based almost exclusively on the web—the emergence of ‘post-internet art’ ostensibly signaled the end of a period during which the internet existed as a discrete phenomenon distinct from broader human consciousness. Altmann’s practice does exemplify this genre shift in that, although online work is a large part of what she does, the mediums she employs extend well beyond pixels. She uses algorithms, objects, brands, holograms, words, sounds, and so—extensively—on. Her projects tend to be aggregations of the above that exist simultaneously in multiple spaces, both virtual and IRL, without defined boundaries. Frequent tropes include mud bathing, eyeballs, lizards, clear gels, mobile phones, technical athletic footwear, and shapes that generally blur distinctions between life form and machine.

Press has also tended to offer the artist up as something of a digital mystic, attributing prophetic qualities to her various content clusters. Hyperbolic as this is, in internet time, to be fair, Altmann is pretty ancient. Her career has spawned and spanned numerous digitally-based microcultures. Two prominent, ongoing examples are R-U-In?S and Garden Club. At the heart of these projects, collectively sourced Tumblr accounts gather things (primarily images, but also texts, tracks, and documentation of related installations and events) and make them available for reblogging. This, in turn, seeds new affiliated microblogs and projects that feed back into their progenitors. The header text for garden-club.info, at time of writing, reads: “WHAT MAKES YOU VIRAL? (CLIMATE CHANGE, GO GREEN, ECOPIA, RAPIDSHARE)” In a text on her artist website titled “Soft Brand Abstracts: World Exposé”, Altmann explains that R-U-In?s operated from 2007-9 as a “communal exchange between a clique of content recyclers in conceptual proximity”.

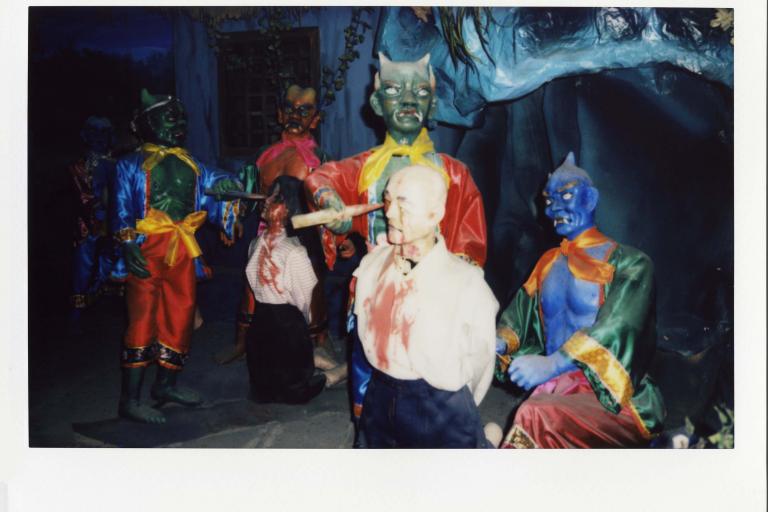

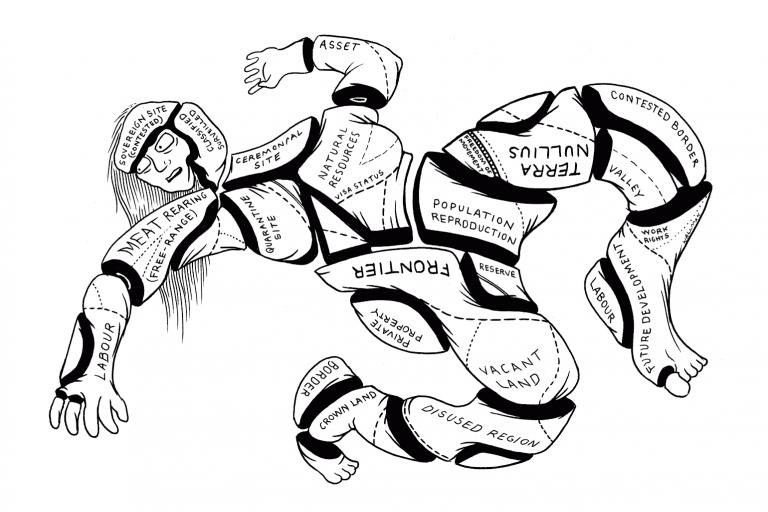

In this same “Soft Brands” text, she discusses ‘Big Product’ and ‘Culture Product’. Loosely speaking, each product form continuously co-opts the other: one attempts to extract capital from what may once have been cultural entities, the other attempts to cultivate pods of culture with, and within, a capitalized infrastructure. In this flux, the micro impacts the macro as much as the reverse, though in a more nuanced way. Utilizing small adjustments is, in fact, a core mechanism of Altmann’s practice. If, as journalists have pointed out, her work reads simultaneously as ancient-ritualistic and futuristic-cybernetic, this is likely because it is at once intimately familiar and viscerally strange. She frequently takes well-known entities—chairs, shoes, animals, words—and augments them just enough to push them out into an uncanny realm. Or, she aggregates found and submitted examples of this. In doing so, she gives us a plastic model of ourselves via the networks around us, with outlines that are continuously morphing, emerging, and collapsing. Disconcertingly, perhaps, her work points out that these odd versions are not actually all that distant: her sources are primarily contemporary, and her interventions are fairly minimal. Her art is not an oracle; it’s a slightly warped mirror. (Or, at least, an open-source mirror app for your knock-off smartphone.)

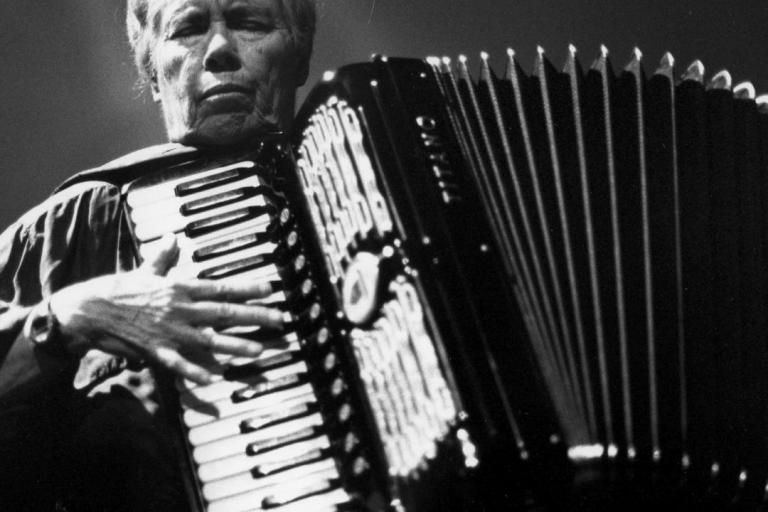

Altmann’s work has long had a home within institutions dedicated to new media and online art, such as New Museum’s Rhizome. In October 2014, she launched her latest piece, Flexia II, on extinct.ly, the online component of Serpentine Gallery’s Extinction Marathon. This was a notable step into more traditional institutional territory—part of the inevitable breakdown of such medium-based art world boundaries. For almost a decade now, the Serpentine has been hosting an annual ‘Marathon’ day or weekend of talks and projects; in 2014, they chose ‘Extinction’ as their theme. The event was curated in collaboration with Gustav Metzger. Now in his 80s, Metzger is best known as the creator of auto-destructive art and for a life dedicated to political activism. In recent years, he has focused on global extinction. Situating Altmann’s work in close proximity to Metzger’s revealed important and maybe unexpected aspects of both. Extinction Marathonpresented Metzger’s first digital work: a live broadcast of the artist’s ongoing piece Mass Media: Yesterday and Today. First shown at the Serpentine in 2009, during the 2014 Marathon, it was installed in Canterbury’s Herbert Road Gallery as Facing Extinction. Though the project is continuously evolving, the core of Mass Media is thousands of stacked newspapers. The public—or, in the case of Facing Extinction, a Canterbury student body—is invited to cut clippings out of the papers and paste past them on surrounding walls.

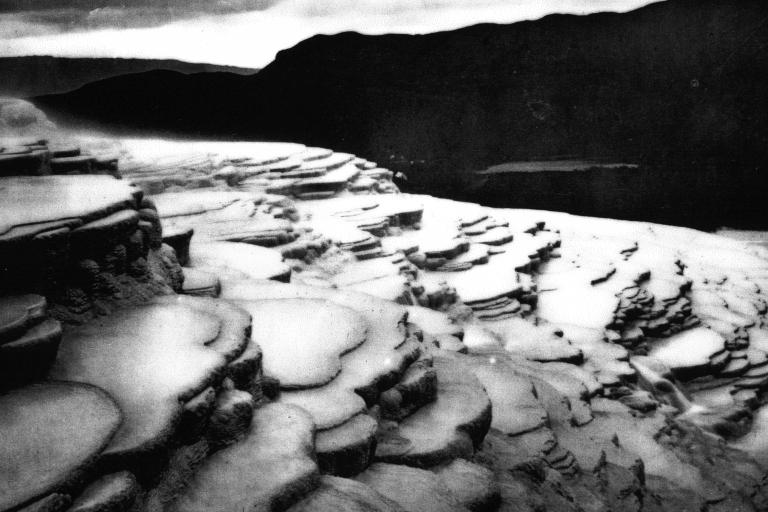

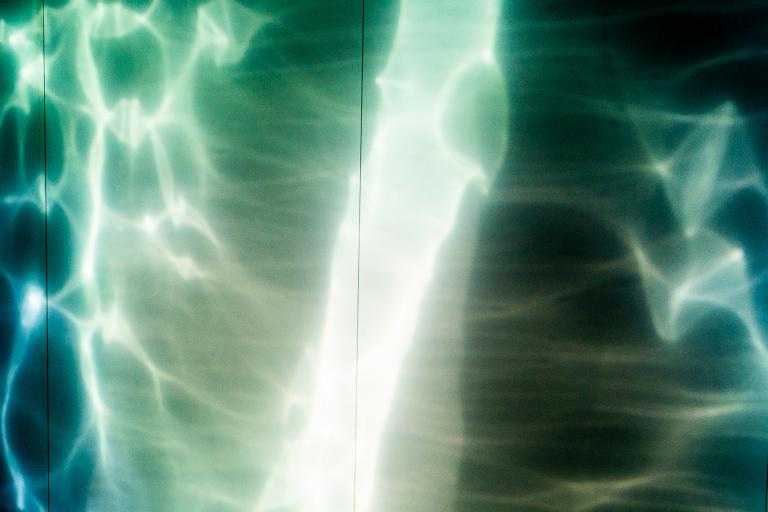

As for Altmann’s Marathon project, when Flexia II went live, Serpentine tweeted: “Watch @_flexia_ by @karialtmann, which brings together disparate sets of content with survival tactics and language.” The ‘survival tactics’, in particular, may not necessarily be widely accessible. The two-minute forty-second video is a morphing conflation of product and landscape. The sweeping arc of a high-performance running shoe transitions with transparent layers from evoking forested mountain ranges to icebergs. The soundtrack features cinematic, African-sounding drums and vocals of an expansive, inspirational sort. From time to time, the ping of a notification interjects, mildly simulating a real-time experience: the pop-ups offer a new upload from a social media contact, a promo code for a product sample. This is all overlaid with a series of words that congeal momentarily out of a colorless CGI liquid and then splash out of existence. To an English speaker, at least, most of these words have no particular immediate reference but bring to mind biotechnology, Latin, and far-flung regional dialects. Popping the words into Google reveals sources that range from Nike products to hair products. “Xperia” is a Sony mobile phone; ‘stimulastine’, a wrinkle cream. @_flexia_ , the associated Twitter account, tweets similar words and phrases, including those featured in the video. This use of language, typical of Altmann’s practice, is another reason she can come across as future-y. As a general dissatisfaction with the term ‘post-internet’ implies, even culture seems to be changing faster than our official lexicon can match. Despite the Oxford Dictionary Online’s specialized focus on current usage and its admission of around 1000 new words per year, it is still too cumbersome to deal with the explosive intersection of human language, digital algorithms, and the global marketplace.

Flexia II, specifically, could read as a product launch, a film trailer, that emotionally charged ending sequence of a Pixar movie that implies the adventure is just beginning. It references brands, like Nike, that trade on heroic associations of personal achievement aided by science that has been influenced by nature, gesturing towards the mutant, the hybrid, the human who literally sprints as fast as a cheetah, as if we were, obtusely, trying to return to wild by way of technology. In terms of such image crafting, an audience will generally understand that it is being manipulated. Knowing someone wants something doesn’t necessarily negate immediate emotional responses, but there can be a detachment from those emotions. One may feel spontaneously uplifted by the traditional African music Altmann has selected, but considering the brutal economic exploitation of the African continent, referencing its cultural forms while simultaneously referencing commercial brands might also induce nausea. In learning to analyze reactions to nearly everything continuously critically, feelings can be exchanged for feels. Altmann’s work can expose gaps between emotional flatness and connectivity that seem to be opening around us continuously. The degree to which she bridges these gaps is neither a given nor a constant, but she offers scope for using these spaces imaginatively and fruitfully—a strategy which may ultimately have a great deal of bearing on our continued existence, cultural or otherwise.