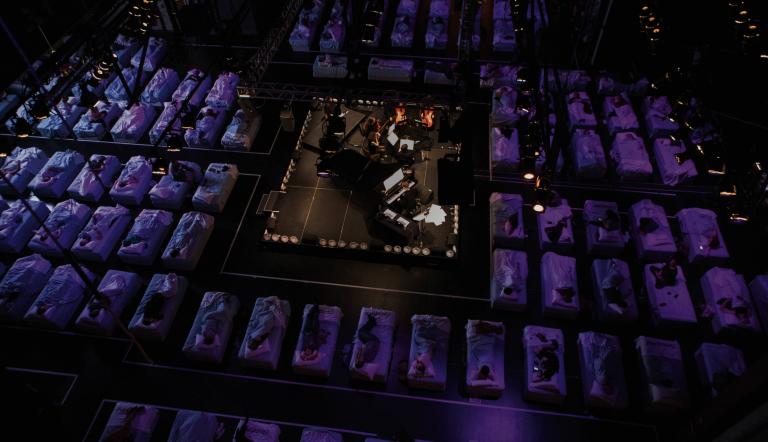

The occasion on this May 4th is a performance of Max Richter’s eight-hour composition Sleep, by Richter and the American Contemporary Music Ensemble (ACME). The piece has been performed only a handful of times since its 2015 premiere in London. It is, I tell myself, a big deal, an important opportunity for the cultural observer, and one that, I guess, by being there, I’m supposed to miss.

Two relevant factors define my partaking in this experience. The first is that I like Richter. Or rather, I liked the record he released before the eight-CD Sleep set. His 2012 album Recomposed by Max Richter: Vivaldi – The Four Seasons was an imaginative and entertaining reworking of perhaps the best-known set of violin concerti in the world, and one for which I’ve never particularly cared.

I bought a copy of the Sleep box (a condensed, one-disc cat-nap version was also released), but I’ve never quite been able to determine whether I like it or not. It’s a curious project. Like his Four Seasons, it’s a clever gimmick, but Richter has the chops to pull off the Vivaldi gimmick. With Sleep, it would seem, chops get in the way. If the music gets too interesting, the project will likely be a failure.

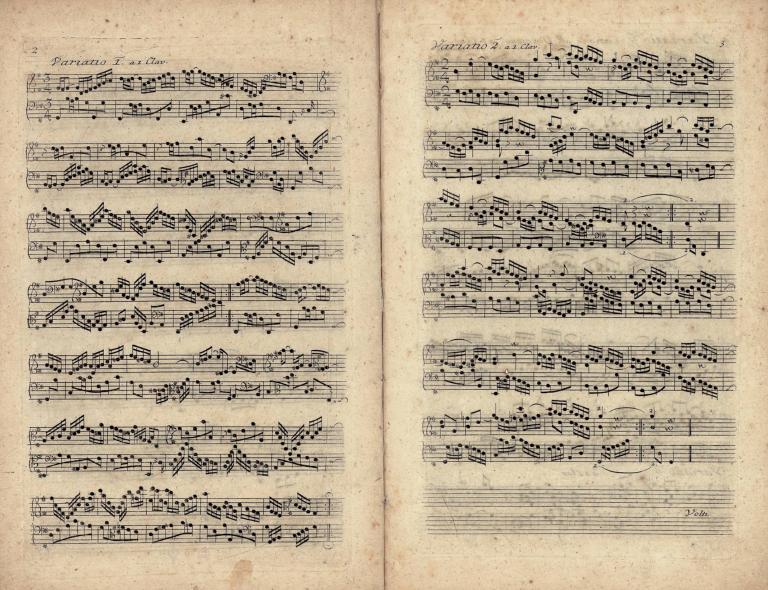

Consider as a parallel a more famous composition supposedly meant for sleeping: Bach’s “Goldberg Variations”. Let’s imagine for a moment that this set of keyboard pieces were actually meant to cure insomnia, as history tells us but historians doubt. If Bach actually composed it at the behest of a sleep-deprived Russian count, then it is the biggest flop in his career. How anyone could snooze through the elegant precision and logical progression of the music is, at least to me, a mystery.

But even if the Bach story is apocryphal (as seems to be the case), others have explored such ground prior to Richter. Erik Satie and Brian Eno both wrote music meant to be experienced passively. They might not have stated that it’s music for sleeping, but I imagine either would have been delighted with that outcome.

The oddly initialed R.I.P. Hayman designed Dreamsoundevents for audiences in the 1980s and even used the “Goldbergs” as a soundtrack. Composer LaMonte Young plays his recorded drone music in what he calls a “dream house”, where visitors can listen, meditate or, yes, sleep. And certainly, all-night music has long been a fixture in India, a region from which Young has drawn much inspiration. I once partook in an event organized by the Dance Theater Workshop in which the group of attendees traveled together from New York to Baltimore, shared a meal, and slept on a church floor while music was performed for us. The intent, we were told in the morning, was to try to cause us all to have the same dream. Unfortunately, it was too warm in the church for any of us to sleep.

There are online playlists, white noise machines, and smartphone apps intended to sonically ease the busy mind. DJ Tom Middleton made an album to quiet the restless mind, and DJ Miguel Santos hosts Sleeping Dogs Lie, a show on London’s Resonance FM crafted for sleepless nights. Curious about this programming for the subconscious mind, I asked Santos about his inspiration for the program.

“I’ve always liked ambient, calm, minimalist, drone music,” he told me by email. “I think the idea for Sleeping Dogs Lie came from listening to Morton Feldman’s Pieces For More Than Two Hands — half a dozen pieces for every formation, from three hands to five pianos, which I used to listen to late at night and considered the perfect music to fall asleep with. I particularly liked its tempo and how each note breathed, dying into silence. I thought it would be a good idea to do a show with music to let people relax, and if they would fall asleep while listening to it, perfect! There were lots of artists whose music would fit the idea (from Morton Feldman, Walter Marchetti, Giya Kancheli, Henryk Górecki or Arvo Pärt, to Brian Eno, Éliane Radigue, Eleni Karaindrou, to Robert Rich, Pete Namlook, Thomas Köner, William Basinski or Max Richter, to give just a few examples). And here we are now with almost 500 hour-long shows done.”

Like those apps and playlists, Santos’ show is, of course, meant for sleep. But what about when you’re not supposed to fall asleep? I asked Santos if he’d ever fallen asleep in a concert.

“I may have drifted in some concerts, yes, but to be honest, these days, I am always afraid of that,” he replied. “I fear I may snore.”

The second relevant factor defining me as a Sleep listener is that, like Bach’s benefactor Count Hermann Karl von Keyserling, I am something of an insomniac. Not as bad as some, I’ll gladly admit, but sleepless nights are not foreign to me. I also have what I would characterize as low-level social anxiety. So a roomful of strangers is not a place where I would ordinarily choose to sleep, even if I could choose to sleep. And yet, here I was, standing in line trying to identify who might snore.

We’re let into the building and take an elevator to an upper floor. I claim a spot in front of the soundboard and next to the window, not so much to be in the audio sweet spot or for the view but so as to have the least number of people around me. I settle in and commence scribbling in my notebook:

I see a woman reclining and reading in her bed, wisely sticking to her evening routine. Others are chatting and sipping cocktails, like it’s just the next crazy thing in their lives of crazy New York City events. Nearer to me, two friends are going over the plans they’d already mapped out: They would listen for a couple of hours, then sleep for three hours, then wake up to listen to the rest — although how that was to be accomplished, I don’t manage to overhear.

Someone walks onto the stage, goes over emergency procedures and introduces a video advertising the mattress company that provided our accommodations for the night, then tells us that we will get underway soon. During the intervening minutes before Richter takes the stage, I am a member of what might have been the quietest audience I’ve ever encountered.

Richter comes out and describes the piece we are about to hear, or not hear, or kind of hear, as a “laboratory into how music and our mind can fit together and an invitation to pause — our lives are very busy”. He then tells us that since the audience is expected to sleep, snoring shouldn’t be considered rude. At the same time, he says, it’s also OK to gently nudge your neighbor if their snoring proves disruptive. I write in my notebook:

So, it’s gonna be that kind of party?

In truth, my interest in attending isn’t, strictly speaking, Richter’s music. Nor is it the opportunity to do the next craziest thing ever in my crazy New York City life. For several years now, I’ve been thinking about the phenomenon of sleeping in concerts and the shame we attach to it. That we can hear and process information while sleeping is clear. Hearing your name spoken can rouse you from sleep, and a television or radio left on can induce dreams. But unless they’re snoring, as Richter acknowledges can be irritating to others, or maybe drooling, which might be embarrassing, I don’t see why we should scoff at concert drowsers. Is it because it’s rude to the performers? If so, I would suggest to those performers that I doubt people often sleep during a concert by choice, so they need not be insulted. Sleep is, of course, a biological necessity and sometimes can’t be fought off. The shame, perhaps, is because we think the sleeper is missing out on a cultural event that they’d clearly cared enough about to attend. But after giving the matter considerable consideration (including some field research sleeping during concerts myself), I’ve come to believe that we’re not missing out, we’re just listening differently.

Of course, if I want to pay close attention to the music and have vivid memories of it, then sleeping would be a detriment. But tonight is an exception. This is a concert meant for sleeping. I write in my notebook: What if I didn’t already have the CDs? Would I feel like I was missing out? Even still, what if I want to hear it? Or for that matter, what if I have a bit of crowd anxiety and don’t feel prepared to sleep in a room full of strangers? (The answer to that, I suppose, would have been to just stay home.)

Do I miss out if I don’t go to sleep?

Is the music interesting?

Is it bad to say it’s not?

We’re 15 minutes in, and I’m finding I don’t want to sleep. Have I ever attended a concert where I wanted to sleep? After dinner at Victo, I accepted the inevitability of it.

The first concerts after dinner at Victo — more properly, the Festival International de Musique Actuelle de Victoriaville in Quebec — were some of my first and deepest sleep-listening experiences. I attended the festival annually for years, and the long days, with concerts running from noon until after 1 am, were only interrupted by meal breaks. The 7 pm concerts were held in a movie theater, which is to say a dark, windowless room with big, comfortable seats. The post-dinner crash was something I came to accept, even to count on.

I wasn’t the only one. At a 2007 concert by songwriter Carla Bozulich, a man came in late and alone (his red shirt and white beard making him look like nothing so much as Santa Claus on summer break), went straight to the front row, sat down, and within minutes was loudly snoring. Rather than taking offense, Bozulich cooed like she was looking at a baby in a carriage, sat on the edge of the stage, directly in front of him, and serenaded him. Musicians who take offense at sleeping audience members might be wise to take a lesson.

The opening section is all piano with a repeating electronic bass, Richter and his laptop the only ones on stage. And in fact, while all of the members of ACME will get breaks over the course of the night, Richter will remain on stage the entire time.

Richter has said that deep tones are believed to help induce sleep, but the volume at which they’re being played is surprising, to say the least. The room is lit in a soft blue, augmented by the city lights from outside. Within the first half-hour, almost everyone has diligently reclined in their beds, if only because there’s no back support.

The strings come in, also amplified a bit louder than might be expected. It is quite beautiful, if more like Michael Nyman than Bach. But good Lord, who could sleep to Bach?

Popular myth has it that Bach was commissioned to write his “Goldberg Variations” by the aforementioned Russian ambassador to the electoral court of Saxony, Count Kaiserling. The set of harpsichord pieces was to be played by court musician Johann Gottlieb Goldberg during the Count’s not uncommon restless nights. The majesty of the pieces, it seems, was meant to occupy and ease the mind — although I find it so utterly exciting I can’t imagine sleeping through it. Not sleeping well, anyway.

I have a habit of leaving the radio playing day and night for the last week of every year through the WKCR Bach marathon. During the 2017 broadcast, I found myself struggling to get to sleep at 2:30 am on Christmas night in my mother’s overheated basement bedroom. I labored in a half-dream, imagining an overzealous black-and-white Mickey Mouse attacking the piano, which groans in protest. His left hand, maneuvering the trills and repetitions, sounded as if a CD were skipping. Was it? Either way, was this the stuff of lullabies? I wouldn’t think so.

I did intend to sleep through the “Goldbergs” once, more or less: December 2015, at New York City’s Park Avenue Armory, with lighting design by Marina Abramović. Rather than beds, we were given low-slung chairs (a bit like sitting hammocks), and the sleeping was to be done before the piece. We were let into the cavernous space (without shoes or cell phones) and told to rest in silence for 30 minutes, at which time the concert would begin. When I heard a gong softly sound, I was surprised to discover that I’d actually nodded off. I did my best to stay in the sleep state as the pianist, Igor Levit, played the set of 30 variations. Brilliant as he was, what I remember most about the evening is how disoriented I was when I left. I walked up one street and down the next, unsure where to catch a crosstown bus or even which way was north.

Not to split hairs in hindsight, but that concert was rather the opposite of the “Goldbergs” tale we’ve been told. The music wasn’t lulling us to sleep but, in fact, waking us up. I witnessed a better characterization of that “Goldbergs” mental state in October 2017 when Simone Dinnerstein played the variations, accompanied on stage by Pam Tanowitz Dance, at Montclair State University in New Jersey. With the stage lighting changing throughout the course of the 90 minutes and seven dancers circling the piano in Tanowitz’s bustling choreography, Bach’s masterpiece was more like a full day’s activity than a full night’s sleep.

Seeing as most historians now dismiss the popular “Goldbergs” origin story as apocryphal, we should probably leave poor Goldberg out of it altogether and start calling the piece by the name Bach provided on the title page:

Clavier Ubung

bestehend

in einer

ARIA

mit verschiedenen Verænderungen

vors Clavicimbal

mit 2 Manualen.

Denen Liebhabern zur Gemüths-

Ergetzung verfertiget von

Johann Sebastian Bach

Königl. Pohl. u. Churfl. Sæchs. Hoff-

Compositeur, Capellmeister, u. Directore

Chori Musici in Leipzig.

Nürnberg in Verlegung

Balthasar Schmids.

“Keyboard exercise consisting of an aria with diverse variations for harpsichord with two manuals. Composed for connoisseurs for the refreshment of their spirits by Johann Sebastian Bach, composer for the royal court of Poland and the electoral court of Saxony, Kapellmeister & director of choral music in Leipzig. Published in Nuremberg by Balthasar Schmid.”

(It should be noted: 43 words in the title and not one about sleep.)

If Bach had really written a piece of music so boring as to lull the listener to sleep, would it still be remembered today? Perhaps so. More people, no doubt, can hum Brahms’ “Wiegenlied: Guten Abend, gute Nacht” (commonly referred to as “Brahms’ Lullaby”) than Bach’s variations, even if they don’t know the former by name. But maybe that’s the exception that proves the rule. Will Richter’s piece be remembered 300 years from now? Does it matter?

For that matter, what does it mean to write for a sleeping audience? It would be hard to argue that many forms of artistic expression can be taken in while sleeping.

The inescapable problem is that sleepers don’t see what’s in front of them. Reading is out of the question; paintings are lost on the snoozer; film is certainly all but entirely outside of what can be absorbed while unconscious. But our hearing remains.

Comedian Andy Kaufman once addressed the possibility of entertaining the slumbering. In a recording made before his fame but only released posthumously (the track can be heard on the 2013 album Andy and His Grandmother), Kaufman puts dreamlike skits, stories, and nonsense oratory against gentle flute and percussion music, along with the sounds of deep breathing and a laugh track. Call it lie-down comedy, call it somnambulist sound art, but its closest predecessor is the Beatles’ notorious “Revolution 9”, which also might be good for sleeping. It strikes me now that the word ‘dreamlike’ is terribly overused.

I’m not really trying to fall asleep in my bed in this room full of concert-goers. I feel very present. With nothing to lean against, I’ve quickly given up on the notion of watching the band. Instead, I’m lying on my side, watching the traffic circle outside the window. The patterns of the cars and the repetitions of the music remind me more than a little of Koyaanisqatsi, the 1982 film of busy people going about their busy lives to a soundtrack by Philip Glass. I think about Glass and how his might be ideal sleeping music, and then I recall that I actually have slept at one of his concerts — although not by choice.

It was August 2013, at the Ostrava Days festival in the Czech Republic, and I had arrived on the afternoon of the opening concert: the Philip Glass Ensemble playing the composer’s Music in Twelve Parts. Jetlagged and in a theatre seat not conducive for sleeping, I nodded and struggled my way through the five-hour performance. At this point in time, I’m not sure I could honestly say that I attended the concert. It feels shameful to admit it, but sometimes it can’t be helped — almost all of us sleep almost every day, and sometimes the timing is less than convenient.

But given a proper bed, like this nice one supplied, Glass would be fine music for sleeping — better than that other signpost of New York minimalism, Steve Reich. Reich is too full of tension, which is why I prefer his work, at least when awake. Although sleeping during a performance of Reich’s work, in my experience, has been more pleasurable as well, if only by virtue of the furniture provided.

I had the occasion to sleep through a performance of Reich’s “Music for 18 Musicians” at the 2007 Bang on a Can Marathon at the World Financial Center’s Winter Garden Atrium in Lower Manhattan. It was a bit of curatorial brilliance in a program that was scheduled to last 24 hours but stretched toward 30, with the Bang on a Can All-Stars playing their arrangement of Eno’s ambient masterwork (if there can be such a thing) Music for Airports, starting at 1 am, and the Grand Valley State University New Music Ensemble playing Reich’s “Music for 18 Musicians” at five in the morning. I wrote in my notebook at the time:

I do think BOAC’s record of Eno’s Music for Airports is pretty beautiful, and it might be a nice thing

to sleep through as well. It’s a different level

of music appreciation.

I had managed to stay awake through the Eno piece but dozed off soon after, missing a piece by the Russian composer Galina Ustvolskaya, who I’ve since grown to like quite a bit. (The question arises again: Did I really miss it?) And waking to Reich’s percussive, irregular loops, I watched the sun gradually brighten the sky through the Winter Garden’s wall of windows, carefully positioned on a metal bench big enough for two to sit but not for one to sleep.

I thought back about that long night when considering this article and so took the occasion to speak to composer and Bang on a Can co-founder David Lang about that most marathon of marathons.

“I was there all night,” he told me. “We had designed that very carefully, so we all had time to sleep. We had a little room in the back where we could curl up. I went back to that room, and I stayed in there for nine minutes. I think I was up for 35 hours.

“I’m not sure we assumed the audience would be asleep,” he added. “I think we assumed the audience would leave.”

Marathon aside, I asked him what he thought about audience members sleeping during a performance of his work.

“People sleep,” he said. “Classical music sometimes has an old audience. My dad is 91 (thank God he’s still alive), and he has the right to fall asleep where he wants.”

Attending a concert can, in fact, be a rare and valuable respite during a busy day, he told me, one that doesn’t necessarily demand focused attention.

“It’s a moment we don’t get enough of, a moment where you can be quiet and concentrate on your life,” he said. “It’s the presence of the music that makes that possible. That kind of time set aside for thinking about yourself is something we don’t get in our daily lives. It’s like a public space for meditation. It doesn’t have to be a thing that bosses us around.”

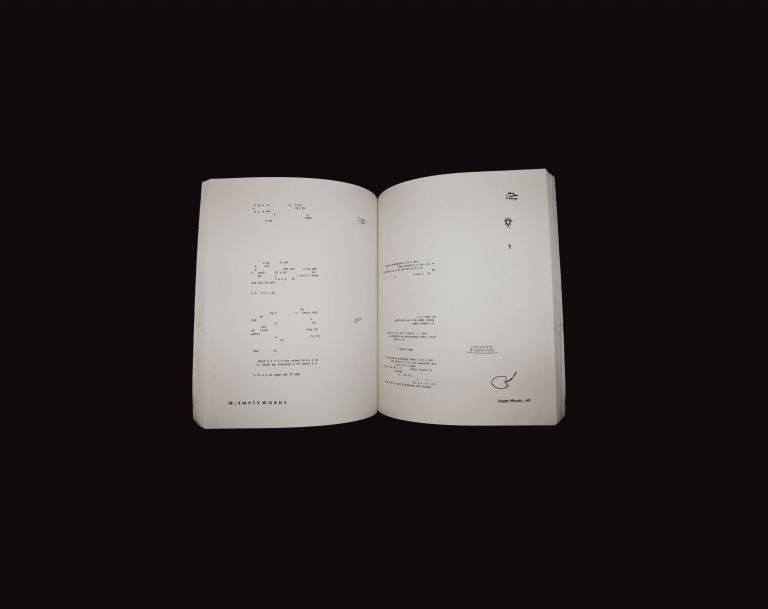

I asked him if he had any memories of sleeping during concerts, and he recalled seeing John Cage perform Empty Words as a graduate student at Yale. The twelve-hour performance clearly made a lasting impression.

“I was told to bring a sleeping bag and a pillow,” Lang said. “It was unbelievably boring. I put my head down and fell asleep, and when I woke up again, it was like waking up in a forest. He was mumbling words out of Thoreau. It really changed what I was paying attention to. As a composer, you’re telling people that what they need is this beautiful melody, and you say, ‘I want you to appreciate and value the music.’ You have to convince the listener to meet you on those grounds. I woke up without all the preconditions about what makes music music. I heard how amazing the sound was. It was there waiting for me whenever I woke up. You get the sense that the thing you’re observing is eternal, and you’re lucky to experience as much of it as you can.”

My whole venture with Richter, I realize, was misguided. I’d been thinking about why sleeping at concerts is frowned upon, but this is a concert during which you’re supposed to sleep. I was missing the point.

I think back on my previous experiences of unsanctioned snoozing: One came during a concert the previous September that I was greatly anticipating.

It had been a long day of work, followed by a rush to Roulette, in Brooklyn, for Joan La Barbara’s appearance at the 2017 Resonant Bodies Festival. I took my seat and, within minutes of her taking the stage, was sound asleep.

I awoke during the final minutes of the piece, disappointed I’d missed it and hoping that no one had noticed. This, more so than the Richter, was an example of the problem with which I was concerned. I emailed La Barbara and asked her if I could give her a call.

As gracious and good-humored as she is talented, La Barbara laughed when I told her I’d slept through her set.

“Maybe that’s good,” she said. “Maybe it’s soothing.”

I asked her if she could recall having fallen asleep at a concert and, ever poised as she is, she, of course, could not. But, she said, her mentor, Morton Feldman, often drifted off in concert halls. In particular, she remembered a concert in the 1970s at the California Institute of the Arts of Cage’s Songbooks and Winter Music.

“During a long silence, the only sound you could hear was a loud snoring, and it turned out it was Morty Feldman,” she said. “Morty famously fell asleep in concerts of his own music and other people’s music.”

The piece she performed at Resonant Bodies was an easy one to sleep through: “The River Also Changes”, a new 45-minute composition for amplified voice, percussion, and a prerecorded “sonic atmosphere” of voice and piano. Quiet and with a narrow range of pitches, it’s a relaxing and meditative work. La Barbara forgave me for nodding off during it and even confirmed my suspicion that, perhaps, I wasn’t missing out.

“I don’t have a problem with you falling asleep,” she said. “Sometimes things that we listen to when we’re sleeping seep into our subconscious, and we hear more than we think we do.”

(cf. The Partridge Family, Season 1, Episode 11, in which a sleeping Danny hears Keith writing a new song in the next room, awakes believing he’d written it, and turns out to have improved upon it in his subconscious state.)

Forty minutes in, the entrance of soprano Grace Davidson causes a few to bolt upright. A guy in the front sits resolutely on his phone (the screen too bright for him to be filming). I’m scribbling away in my notebook. The music is getting even louder.

I have seen two perfectly satisfying improv sets in the last two nights: one by guitarist Loren Connors and the other by saxophonist Tamio Shiraishi and vocalist Ami Yamasaki. Neither lasted much more than 20 minutes. Tonight is about 25 times the length of either of those. I recall a claim stated in the booklet that came with the Talking Heads album Stop Making Sense: “[T]he best length for television programs is either 30 seconds or eight hours.” Adjust the numbers a bit, and the same might be said for music. Also according to the booklet: “Singing is a trick to get people to listen to music for longer than they would ordinarily.” Makes sense to me. I scribble in my notebook:

A guy in a Red Hot Chili Peppers tour shirt (assumedly part of the operation) is walking between beds and filming us. You’re never safe.

This isn’t the first performance of Sleep, and it’s not the first time ACME has performed it. The ensemble also plays it on the recording. I was considering myself some kind of champion for even thinking about attending the concert, so I spoke with one of the musicians who plays the piece to knock myself down a notch.

ACME violinist Yuki Numata Resnick told me that she finds it impossible to sleep while music is playing, which is, no doubt, a necessary attribute for anyone performing Richter’s piece — although she did allow that she played Mahler symphonies on repeat overnight as a child.

The ensemble rehearsed and recorded Sleep in sections, she said, so they never experienced the whole thing until the first time they played it live at the Sydney Opera House in 2016.

“The studio recording was so different from the act of performing it in concert,” Numata Resnick said. “I feel like none of us really knew what the project was. Max explained it to us, and it sounded kind of zany. We were like, ‘OK, sure.’ We were recording bars of really, really slow whole notes. We were just recording fragments, and Max later assembled it in the studio.”

Playing it live, however, proved to be quite an endurance test. With the twelve-hour time difference between Australia and the ensemble’s New York home base, the ensemble lived and breathed the piece.

“We essentially all just stayed on our respective schedules,” she said. “Sleep all day, play a concert, eat dinner at eight in the morning, and then go back to the hotel room and go to sleep.

“It’s very controlled; it’s very slow, very static movement,” she said of playing the piece. “You can’t really loosen your muscles like you would playing something quicker.”

ACME’s first performance was a memorable one, she recalled:

“The piece was scheduled to end at sunrise,” she said. “Some people were super diehard; some just settled into their beds right away. But by the end, most people were up and gathered around. It was pouring rain, it was really a beautiful moment.”

Judging from the light outside my window, we’re in the final half-hour of the piece, a fraction, a trifle. I don’t turn on my phone. I don’t check the time, and I don’t check for messages. I try to put off taking out my notebook but after a while grow afraid that too much of the moment will slip away. I write:

I’m unsure of the value of the experience I’ve had. Not unsure if it has a value but of how to appraise it. I realize I feel good. I feel — interested. I think I had an active night of dreaming, but I don’t remember it. (I rarely do.) I feel like a bridge has been established from my sleeping consciousness to my waking consciousness. I watch as traffic picks up outside. For some reason, last night and this morning, I feel little compulsion to look at the musicians who have been working for me — maybe it’s just the angle

of the neck.

I look at the people still sleeping as if they’re missing out. But maybe they’re getting the most out of it, the most

liminal bang for their buck.

The deep, repeating single bass note now resounds with familiarity. It’s comforting somehow, complemented by the single “ahs” of the soprano, complemented by the cellos playing six repetitions for each one of the bass and voice, complemented by the drowsy and the alert people around me, complemented by the streaks of clouds over the Hudson River.

The violins enter again, filling the space, connecting the isolated tones. Richter’s piano is matching the electronic bass notes in his left hand and the cello on his right. (I’m looking at the stage now.) The cellos, too, begin to fill in the gaps.

Is it good music? Is this good? It’s very satisfying, and at the moment, in the early hours of the morning and the final minutes of the concert, I wouldn’t want to hear anything else.

As I ruminate over the next few hours, walking empty Lower Manhattan on an early Sunday morning, I think about the experience of waking up to the music I’d been hearing for some seven hours. I didn’t feel as if I’d missed anything, quite the opposite, in fact. I felt more connected than ever to my sleep state. I think back on something Joan La Barbara said during our conversation, and it seems all the more salient in the chill of this bleary morning:

“I think there’s a very interesting element of the subconscious that we don’t understand,” she told me. “The idea of music entering the subconscious as well as the conscious, I think, is actually a very fascinating thing. There is that analytic thing you can get into — whereas when you’re sleeping, I assume, you’re not analyzing. It’s a different experience and, I think, a valuable experience.”

Walking north to meet a friend for a much-needed coffee, I reassure myself: I didn’t miss a thing. Quite the opposite.