DARK SPACES

I first heard Taiwanese noise and new media artist Wang Fujui in “V-zone” (1997), a track he contributed to the encyclopaedic CD set An Anthology of Chinese Experimental Music 1992-2008 (Sub Rosa). [1] Built around a drone-like tone fed into a vast metallic reverb, juxtaposed against a subtle rhythmic pulse of glitch-sounds, the work references both 1990s Japanese minimalism and European post-industrial aesthetics. One-third of the way into the piece, everything changes abruptly with a brief outburst of sounds that might be birds or children crying out in alarm, followed by a torrent of cascading water. Curiously, this dramatic interjection serves to refocus the listener’s attention on the dark and abstract material of the evolving drone, with its implied reverberant space framing the dancing glitches. At the very end, the source tone of the drone stops, and we hear the reverb fade out for several seconds, catching a significant glimpse of how the sound was put together as it dies away.

In this way, I came to listen to Wang’s work first in terms of music rather than noise or sound art. This has to some extent coloured my appreciation of his work in general. There is certainly a strong musical aspect to his creative aesthetic, even when the work is rather more abstract than we might traditionally expect music to be. By systematically but genially stretching our aural imagination, Wang allows us to experience his remarkably coherent body of work as something distinctively musical yet not always music.

TRAJECTORIES

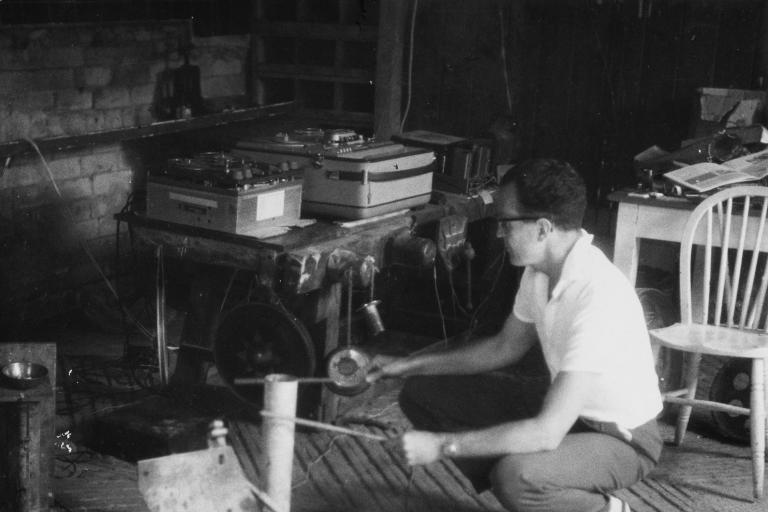

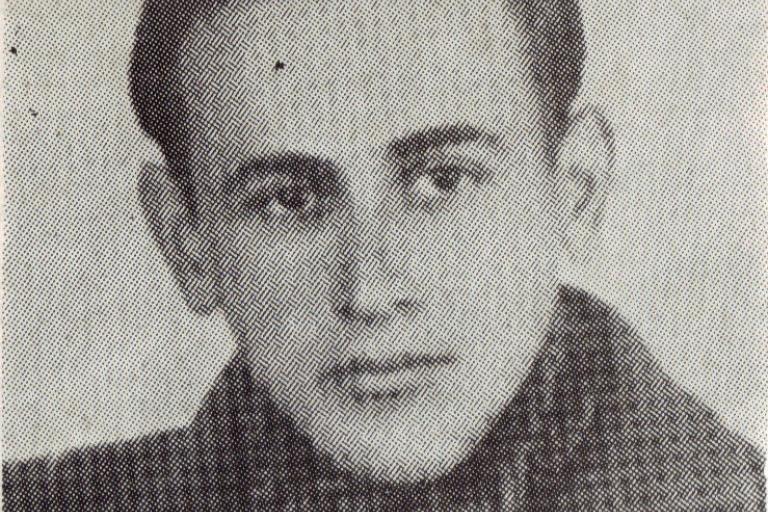

Wang grew up in Taipei listening to music and later studying computer science. Although he worked as a programmer for a while, his early sound-art work was hardware-based, and this fondness for physical controllers has influenced his performance style throughout his career. In 1993, he founded the now-legendary zine and record label NOISE, which had a powerful influence on the experimental noise scene in Taiwan during the 1990s. [2] After two years in the US, where he studied Computer Information Systems at San Francisco’s Golden Gate University, Wang returned to Taiwan in 1997 and quickly became established as a key figure in sound-art performance and audio installation as part of the group of artists associated with ETAT Lab. [3]

Through his work in experimental new media, Wang began conducting research and teaching at Taipei National University of the Arts (TNUA), where he is now head of the Trans-Sonic Lab in the Center for Art and Technology. In recent years, his work has become more widely recognized internationally with performances at major festivals (such as Transmediale in Berlin and Tonlagen in Dresden), exhibitions (Art-Basel Hong Kong, etc.), and in 2014, an extensive tour of China.

PACKAGING SUBVERSION

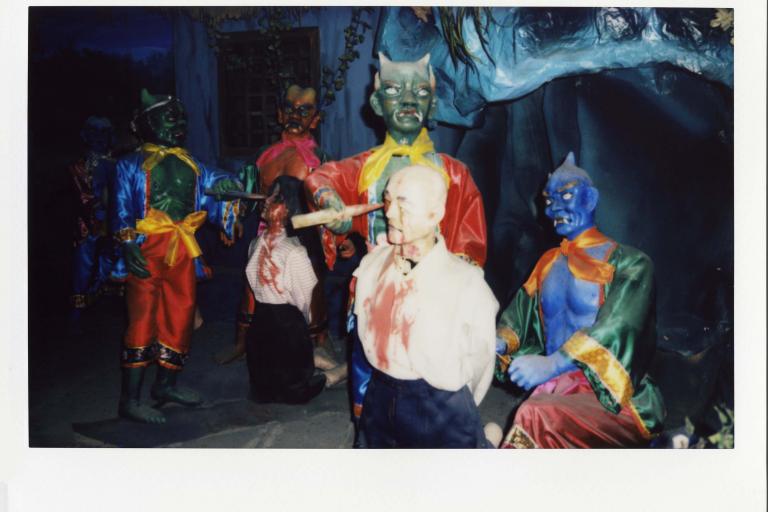

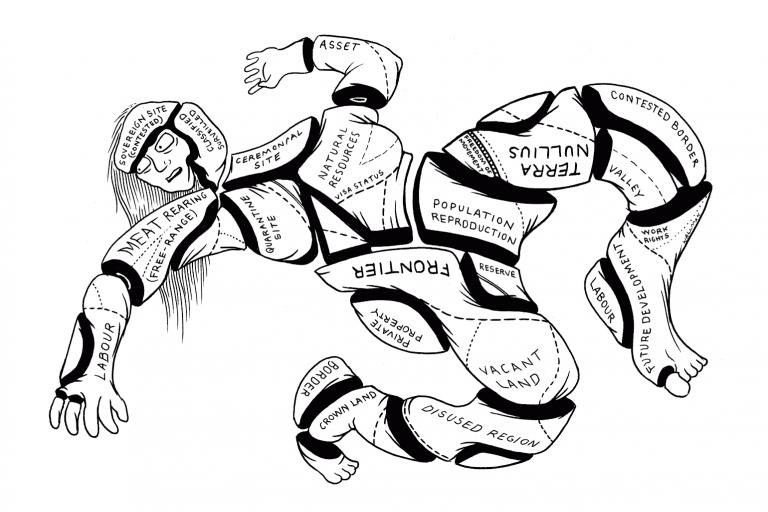

In Taiwan, all music seems to be political. Wang’s early work is often discussed in association with the Taiwanese noise outbreak of the mid-1990s, which is in turn commonly understood as part of the exuberant renaissance of art and music that followed the end of 38 years of martial law on the island in 1987. [4] Artistic productions of the 1990s are broadly assumed, almost by default, to have been pro-democratic. Still, the actual political agendas of those early noise/sound experimenters are harder to reconstruct than popular mythology suggests. Some recent writers have gone so far as to argue that student noise artists were more often naughty rich kids than genuine radicals and that noise is not so much subversion as a “surplus of culture”. [5] This is complicated further by the way some mainstream pop bands have also claimed that their origins in the 1990s confer a similarly democratic cultural capital.

Yan Jun, a perceptive Beijing-based artist and critic, has suggested that the development of noise and sound art in Taiwan is inextricably linked to the transition from martial law to capitalist democracy and that this explains the trajectory of the movement from fringe underground art to packaged and labelled product. [6] A similar argument might be made for bands like Mayday in the pop scene. What is clear is that Taiwanese artists of all kinds have often been working across minefields of unique and potentially dangerous political complexities. [7] By cultivating an open-minded yet critical stance, observing and listening carefully, we may avoid simplistic assumptions.

This is complicated further by the way some mainstream pop bands have also claimed that their origins in the 1990s confer a similarly democratic cultural capital. Yan Jun, a perceptive Beijing-based artist and critic, has suggested that the development of noise and sound art in Taiwan is inextricably linked to the transition from martial law to capitalist democracy and that this explains the trajectory of the movement from fringe underground art to packaged and labelled product. A similar argument might be made for bands like Mayday in the pop scene. What is clear is that Taiwanese artists of all kinds have often been working across minefields of unique and potentially dangerous political complexities. By cultivating an open-minded yet critical stance, observing and listening carefully, we may avoid simplistic assumptions.

LUXURIOUS MINIMALISM

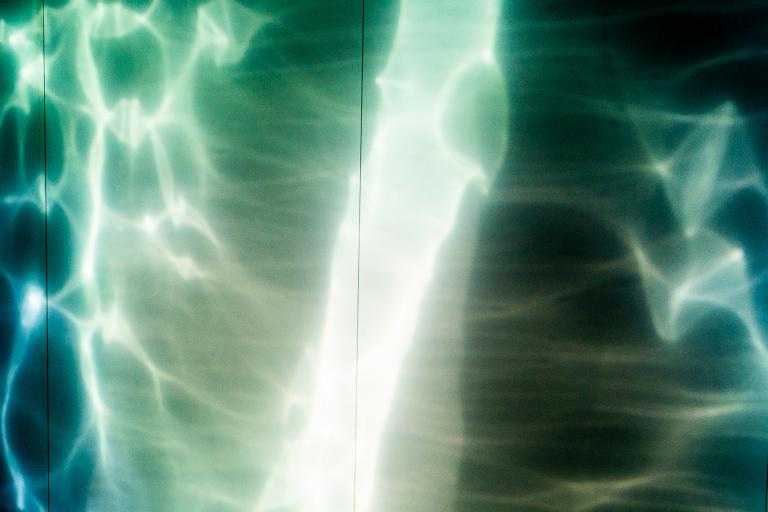

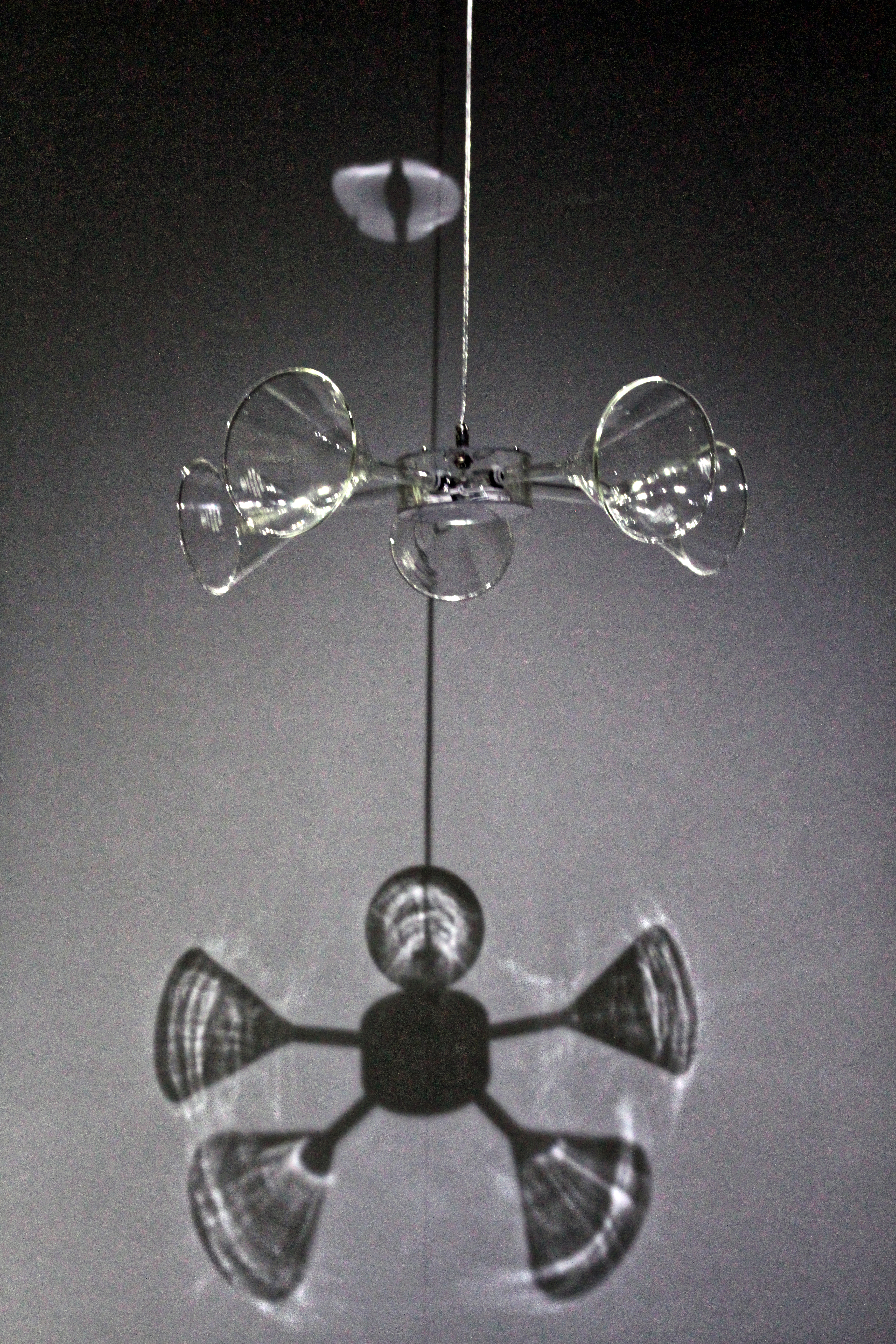

Earlier this year (2014), I experienced “Sound Disc”, one of Wang Fujui’s installation pieces, in the Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts as part of the remarkable exhibition ALTERing NATIVism: Sound Cultures in Post-War Taiwan. [8] This work is visually quiet and minimalist in its lines, forms and colours — being a set of exposed computer hard drives on the wall behind pieces of clear perspex (the controllers and whatever else is required to run the work presumably hidden behind the wall). The drives are active, doing something inscrutable, and their small motors and moving parts busily clicking are the sound source for the audio component of the work. Beautiful, fascinating, elegant and mysterious, this installation draws cleverly upon technology (hard drives with moving parts seem happily retro) and invites the viewer/listener into its quiet orbit with immediate pleasure, subtle and unanswerable.

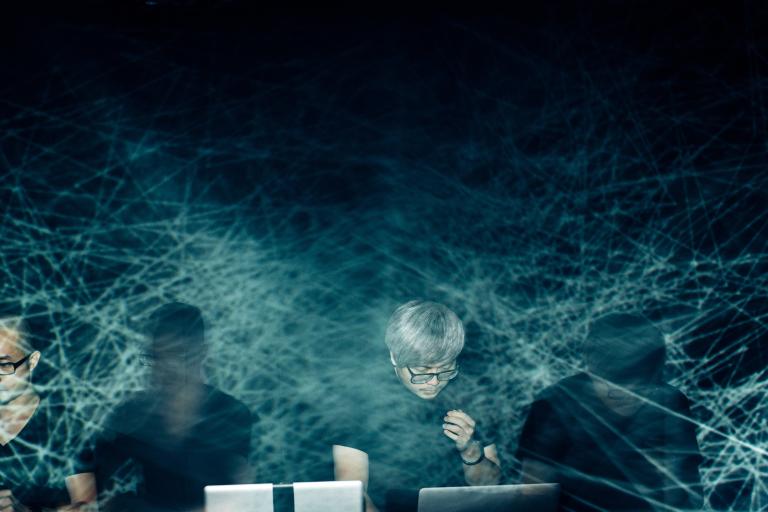

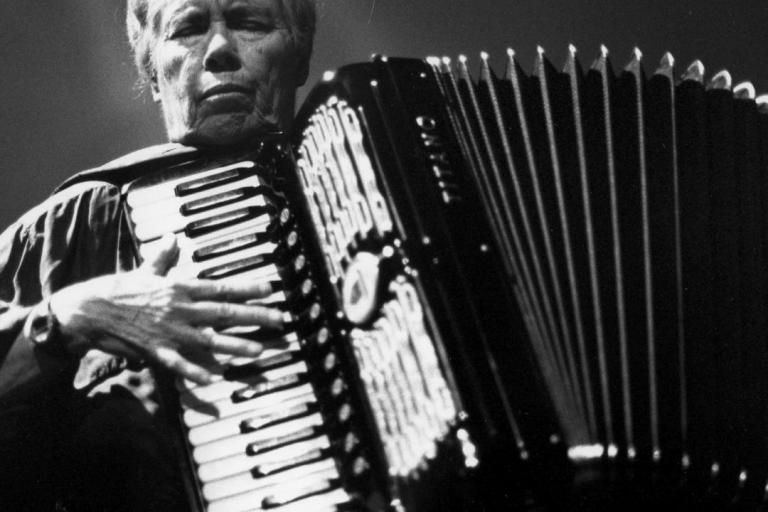

In live performance, we discover a more theatrical side to Wang’s creative personality. He plays his economical desk of gear like a one-man rock band. There is refined showmanship to his gestures but also a concentrated involvement with the sound and shape of the piece as it unfolds. He is the Jimi Hendrix of noise art, only without the lighter fluid and matches. Yan Jun describes Wang’s live performance as “so beautiful and elegantly wild”. [9] Wang, on the other hand, has been heard to speak of his live performance works as “familiar but sometimes awkward”, [10] which is perhaps another way of saying the same thing.

INTERACTIONS

In a very fine short film, Damien Owen Trainor has documented a performance that Wang gave at the White Fungus-curated Depopulate 01 in Taipei during 2012. [11] This performance was another example of Wang’s characteristic opposition of tones (both pure and dirty) against pulses and beats. Here, one also perceives very clearly that there is something else going on, with interruptions (like the surprising cries and cascades in “V-zone”) that seem to blur the beats and tones into one another, sometimes cleanly, at other moments roughly. The base material of opposing forces serves as the frame for a space to be opened up in which a mysterious and volatile third substance arises as a result of Wang’s interventions. This, it seems to me, is where we hear the real voice of Wang Fujui, going beyond the planning, preparation, design and technology, and bringing some new thing into our lived experience.

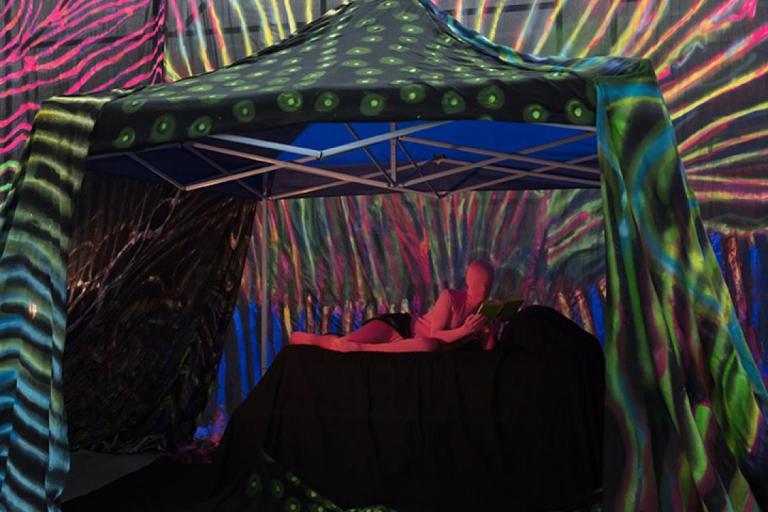

Wang’s performances, however, are not always loud — not always so pulse-driven and not always so visible. At Lacking Sound Festival in 2011, Wang performed an absorbingly slow ambient work, “Inaudible Sphere”, in total darkness. [12] Here, instead of tones against pulse and beats, one heard noise against tones — the tones, in this case, are the ghosts of chords and notes, material drawn from what might once have been music set against shifting scans of radio white noise.

COMMUNICATION

As an artist, Wang has sometimes spoken of an interest in extremes. [13] We find this not only in his sound work, with the binary oppositions of tone/pulse, loud/quiet etc., but also in his cleanly designed visual and installation work, with a palette tending strongly to black and white (plus grey). It is the grey that I think is most crucial — even a work built of black and white materials will cast shadows in varied shades of grey, and this seems to me very important for appreciating Wang’s work in general. At first glance, or first listening, we often find two base materials, but with deeper attention, we start to hear the movement in the shadows. We might think of this in terms of Henri Lefebvre’s notion of the three-part dialectic, where one always finds not just this and that, but also the other thing. [14]

Similarly, a binary political analysis of Wang’s work is unhelpful. His objectives were never merely rebellious, but they are hardly conservative either. To understand Wang’s art, we have to listen a little more closely. The more of his work I come to know, the more I sense a core that is intimately didactic. Not, I hasten to add, in a pedantic sense of the word, but rather in the experience of skilled communication, humanity and creativity that we have when in the presence of a master teacher. Some things cannot be taught in words.

Wang seeks to communicate through our experience of his work, and we meet him in the mysterious spaces between the beautiful and the elegant, between the familiar and the awkward. His artistic output is very diverse in terms of materials, processes and environments (perhaps also audiences), yet nevertheless maintains a powerful coherence in aesthetic and style. Wang has many ways of communicating with us, but from the 1990s to the present, the message has an unusual and impressive continuity.

Read an interview with Wang Fujui by Alistair Noble here.

Footnotes:

[1] This anthology, curated by Hong Kong-based musician Dickson Dee, is essential listening for anyone seeking an introduction to the experimental electronic sound scene in the Chinese-speaking world. It also exemplifies the canonisation of a certain body of work produced since the 1990s, a trajectory of underground arts transforming into museum exhibits.

[2] In 2013, material related to the Noise label formed the core of an important retrospective of Wang’s early work at The Cube, a contemporary art gallery in Taipei. http://thecubespace.com/exhibitions/lurking-waves/fujui-wang.php

[3] http://www.etat.com/

[4] Huang Ming-Chuan’s extraordinary documentary film 1995 Taipei International Post-Industrial Arts Festival gives some insight into one notably mad x-rated noise adventure during the lead-up to Taiwan’s first democratic presidential election in 1996.

[5] Huang Sun-quan, “If Noise Ever Was, It Was Far From Revolt” in Leap: the international art magazine of contemporary China. (Issue 16, August 2012). http://leapleapleap.com/2012/09/if-noise-ever-was-it-was-far-from-revolt/

[6] Ron Hanson, “Art on the Beautiful Island”, Rhizome (April 2012). http://rhizome.org/editorial/2012/apr/5/art-beautiful-island/

[7] Discussion of Taiwanese cinema is also characterised by such problems. For example, the difficulties with rationalising Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s work as an auteur alongside his propaganda work for the KMT government. See Peng Hsiao-yen, “Auteurism and Taiwan New Cinema” in Journal of Theater Studies (January 2012) 125-148.

[8] http://thecubespace.com/exhibitions/altering-nativism/altering-nativism-en.php

[9] Quoted in Ibid.

[10] “LSF 46 Artist Talk”, Lacking Sound Festival (2011). http://youtu.be/1Th4_81BE4o

[11] Damien Owen Trainor, Wang Fujui at DEPOPULATE 01 Presented by White Fungus (2012). http://youtu.be/GqDObw9ZNYs

[12] Wang Fujui, “Inaudible Sphere” at Lacking Sound Festival 2011. http://youtu.be/h9xHtrEgRa8

[13] “LSF 46 Artist Talk”, Lacking Sound Festival (2011). http://youtu.be/1Th4_81BE4o

[14] For some discussion of this, see Stuart Elden, Understanding Henri Lefebvre (A & C Black, 2004) 36.