In the beginning…

There is the supreme creator Tagaloa-a-Lagi (Tagaloa of the heavens) who traverses the Vānimonimo (the great immeasurable expanse of space) without rest. In this state, he is Tagaloa-fe-alualu-mai – restless, in chaos. Weary, he stops to rest, and beneath him, a rock forms – Manuʻa (Manuʻatele) is this rock. [1] From here, Tagaloa sits to call the other rocks into being. Out of the conscious actions of Tagaloa, Savaiʻi (Samoa), Viti (Fiji), Tongatapu (Kingdom of Tonga), and lastly, Tutuila and Upolu are called forth. He has become Tagaloa-faʻatutupu-nuʻu – creator of lands.

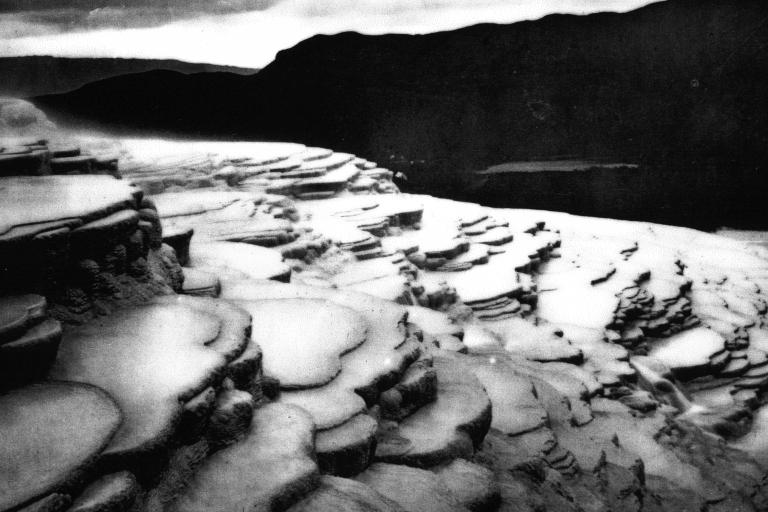

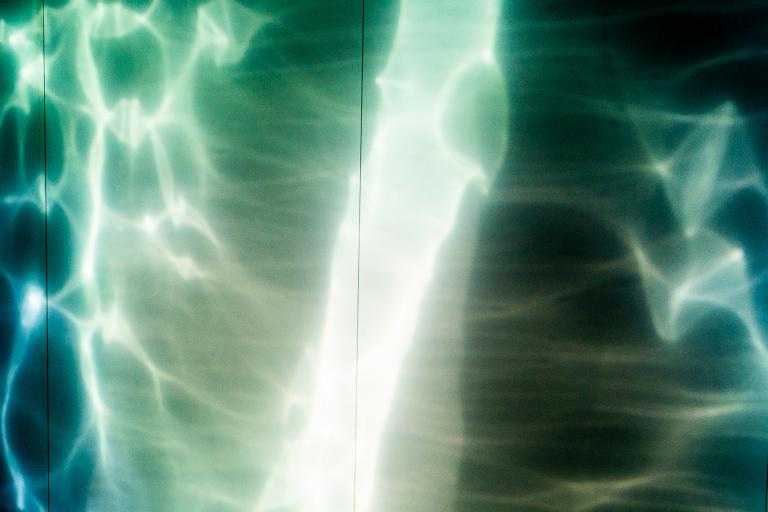

Tagaloa performs many creation works, and one of these is the splitting of rock, from which emerges the ocean, covering the flat areas and ebbing at the edges of these rocks. On the horizon, it kisses the sky. Tagaloa covers the rocks with a sacred vine that produces multitudes of tiny worms. From these worms, Tagaloa creates humans, which he pairs up to populate each Island.

Tagaloa is a supreme being or Atua (deity) — he resides in the ninth heaven. This is written in the present tense to denote the prevailing Polynesian philosophical notions of time as fluid and non-linear.

Tagaloa-a-Lagi is an artist. Fashioning nations out of rocks, people out of worms, and oceans out of split rock. He created the rocks, which are now being slowly swallowed up again by the very oceans that he made emerge from rock. In current time and space, the creation of Tagaloa is being threatened by global warming and rising sea levels.

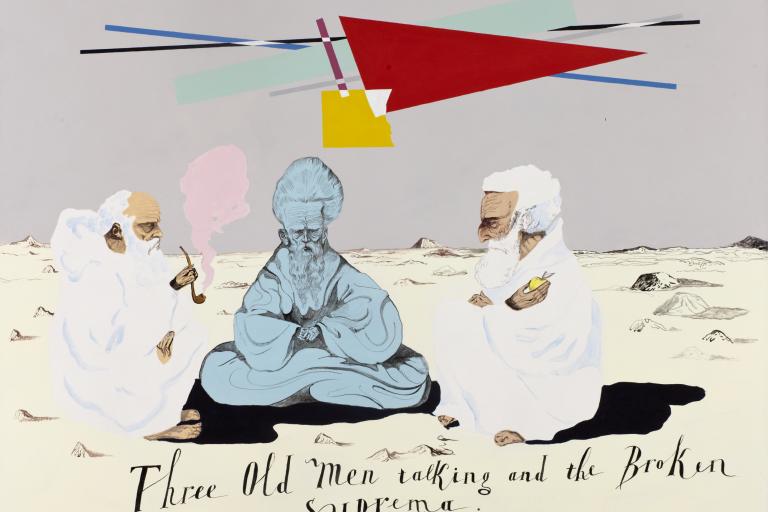

It is not ideal to consider Tagaloa in a Western art context because he operates out of different epistemologies. For a start, Tagaloa is part of an authentic understanding of the world and being. Across so many of the Polynesian island groups, Tagaloa appears in various roles as a god or demiurge. Māori and Cook Islands Māori know him as Tangaroa; in Hawaiʻi he is Kanaloa; and in Tonga, Tangaloa — to name just a few of the islands across Oceania whose lore include him. Western art history emerges from classical philosophical frameworks, classical mythologies, and adherence at various junctures to the Judaeo-Christian trinitarian God. Rationalism and anthropology, and Western art history have largely relegated art from Oceania, Africa, and Asia as craft or ceremonial objects. In stark contrast, art in the Oceanic and Polynesian philosophical sense grows out of the natural relationship of humans to the earth, the sea, the skies, and all living things. This is not to say that the two cannot somehow enter into a talanoa (discussion, telling stories) with one another.

All Kinds of Ebbing Going On

Do not be fooled by the artist’s name, Schaafhausen. It is indeed German; however, the artist was born in Samoa. She is Samoan.

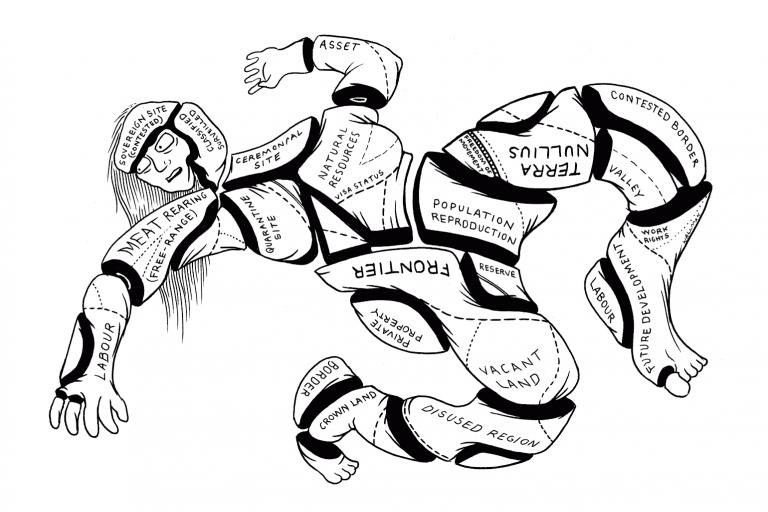

The colonial occupation of Samoa by Germany, under Wilhelm Solf, began officially on 1 March 1900, concluding in 1914 when the New Zealand government decided they would take over. Numerous merchants arrived in Samoa before the actual annexation of Samoa by Germany. This period of history led to a real-time ‘miscegenation’ and cultural exchanges. Like me, Olga Krause, Paula Schaafhausen bears the evidence of Germany’s presence there, generations on from the actual occupation. German Samoa was a real ‘thing’. So already, a psychological and social ebbing of Tagaloa had begun. Europe, the United States, and the long arm of the Empire via the New Zealand government had all set their feet upon the rocks first created by Tagaloa. And Tagaloa had long gone from daily conversation, and memory since Christianity (via the London Missionary Society) crashed like a violent tidal wave swallowing up the land in 1830.

The waves of people and influence and the outside eroding what existed in and around the islands of the Pacific began before global warming.

Coconut and Sand – Not Rock or Wood

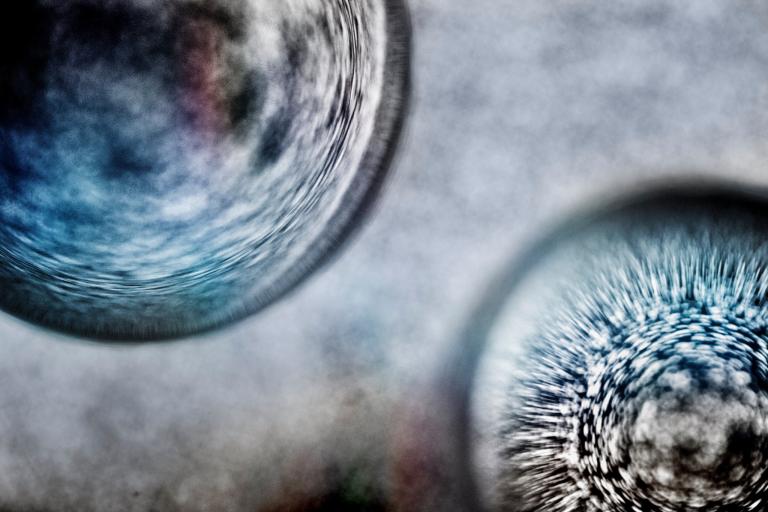

Ebbing Tagaoloa comprises a series of Tagaloa sculptures. Each one is crafted by hand using the ubiquitous Samoan fanuʻu (coconut oil), solidifying when cold. Mixed into each god form are local sands from the beaches near each exhibition venue that has presented the sculptures. Schaafhausen collected sand, stones, plastic detritus to aid in the physical formation of her Tagaloa. So the specificity of location is part of the work and a form of acknowledging that Tagaloa is not absent but present in the form of sand – animistic in the sense that whatever is made with the artist's hands is imbued with an olaga (life).

Coconut oil is to Samoans of the diaspora and indigenous Samoans as English breakfast tea is to the British, or sake to the Japanese. So Schaafhausen’s use of coconut oil as media is selected for particular reasons. Firstly, it has always been a part of her lived experience and is a signifier of Samoa. Secondly, solid coconut is easy to melt and solidify; therefore, easy to shape and carve. It performs a specific action as part of the intended role of each of these little gods.

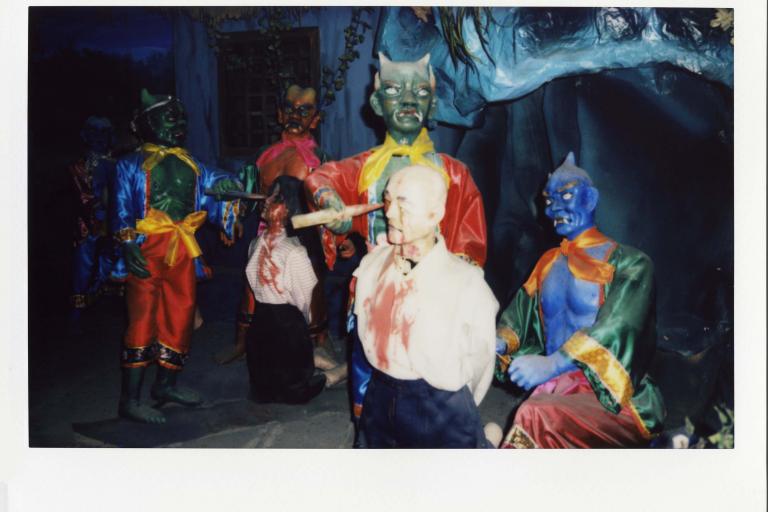

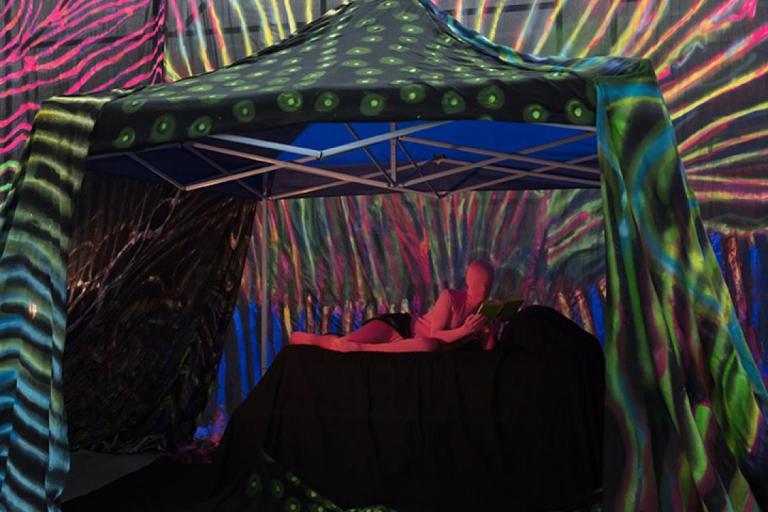

In the image above are twelve Tagaloa, spaced out equidistant from each other in a circle formation on the gallery floor. There are multiples of him, collectively representing the various roles they enacted in creating the world. To make each of them, Schaafhausen visited the twelve most visited beaches in the Eora Nation, Sydney, Australia, and gathered sand and other found objects. They sit in the formation of Matai (Samoan chiefs) in a fale [2]; their gaze is toward each other – in a fono (meeting). Theirs is a quiet ministry: They are without vitrines, without plinths to elevate them, just the negative space between them and the viewers walking around them as though they were mere mortals.

Gallery-goers still navigate their steps carefully out of reverence for an artwork in a gallery. But Schaafhausen’s intention is to liberate the Tagaloa from the signification of ‘museum object’. Like all indigenous arts and most measina (treasures) in Oceanic and Polynesian tradition, they were not created to be separated from humanity and human touch. Here, Schaafhausen directly critiques Western museological and anthropological practices: The enclosure and display of carved Atua, textiles, etc., create an unnatural separation from the people and their own material culture. What underlies the use of a vitrine is the culture of plundering by voyagers and ‘explorers’. The irony is no laughing matter. It makes the saltwater of Tagaloa’s ocean seep through the eyes of his created worm-peoples at natural history museums and the like.

The other aspect, and perhaps even more salient matter Schaafhausen references, is the visceral fact that climate change, and the consequential warming of the oceans, are incrementally subsuming the rocks Tagaloa created. Perhaps it is not discussed enough: that the islands in the expanse of the Pacific Ocean are not major polluters affecting climate change, and yet they are the very ones whose lands will be the first that Tagaloa’s oceans will take back. The worst of these affected are the Tuvalu and Micronesian island of Kiribati. Even some parts of Samoa are slowly disappearing.

Schaafhausen’s Tagaloas are not made of wood, like the early sculptures, nor are they made of stone, marble, or even metal. The artist has selected unstable media. Even the woolen Tangaroa made by Ani O’Neill, from the 1994 exhibition Bottled Ocean [3], were permanent. But not Schaafhausen’s coconut oil– and sand-formed gods. Vulnerable and placed lower than the angels, they sit in a warm gallery. Their slow melt and demise will leave them unrecognizable as proud Atua; they will become mere puddles of oil, sand, and beach-combed trash. Their gradual morphing will eventuate in a physical absence in the gallery space. Schaafhausen’s powerful final olfactory statement is like a punch in the nose. And Tagaloa’s voice will be shouting, “Wake up and smell the coconut!” as you turn your back to leave the gallery and their remnants behind.

The original exhibition of Ebbing Tagaloa was mounted at Enjoy Public Art Gallery (since renamed: Enjoy Contemporary Art Space), Te Whanganui-a-Tara – Wellington, Aotearoa – New Zealand, in a joint show with Suzanne Tamaki in 2014. The most recent iteration was part of the 2020 group exhibition Wansolwara: One Salt Water with Terry Faleona, Rebecca Ann Hobbs, Vaimaila Urale, Ruha Fifita, Shivanjani Lal, and Paula Schaafhausen at 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, Eora Nation – Sydney, Australia.

[1] There are numerous versions of this story, and I have chosen the one which starts with Tagaloa and the first rock, Manu’atele. I have truncated it because the various aspects of Tagaloa’s creation are too numerous to enter into.

[2] Samoan traditional house is a central part of the traditional matai system. Matai meet in a fale tele (formal meeting house) in a similar oval formation. This is a relational spatial arrangement extensively written about by Dr. Albert Refiti, an architect and academic based in Aotearoa New Zealand.

[3] Bottled Ocean, 1994, was curated by the late Jim Vivieaere. In this exhibition were crocheted Tangaroa made by the artist Ani O’Neill (Titikaveka, Rarotonga/Aotearoa New Zealand).