amongst the many reasons that led me to emigrate out of brasil, my inquietude in the face of what i saw as a reigning cultural homogeneity played a big part. back in the early nineties, when i left, my interests comprised a mix of popular culture and subculture imported from either the us or the uk. the available youth culture produced in brasil at that time seemed to me saccharine in comparison.

bands in brasil were started by kids mostly from wealthy backgrounds. many of them had access to travel abroad, bringing back influences picked up from other countries. lyrics would often be shaped around the inevitable third-world realities, but the sounds typically veered towards derivative fare. the same approach was taking place in the visual art produced at that time. not much of the art coming out in those years resonated like what was previously seen during the brasilian response to modernism that lasted through the 70s.

moving to america, i experienced firsthand much of the culture that i had been enamored with from afar. eventually, i learned that these subcultural and more experimental modes of production were also frequently connected to privilege and could be derivative in their own way. often these were even accompanied by an unapologetic entitlement in appropriating the culture of others.

as a result of colonialism, many brasilian artists confronted a cultural malaise in which everything created elsewhere was viewed as better and more deserving of praise. many tended to copy what was being produced abroad. but some artists did manage to subvert the effects of this melancholic tendency. good examples can be found in tropicalia music, the artworks of hélio oiticica and lygia pape. these artists succeeded in utilizing an anthropophagic approach towards information from other places to emerge with something new and very brasilian.

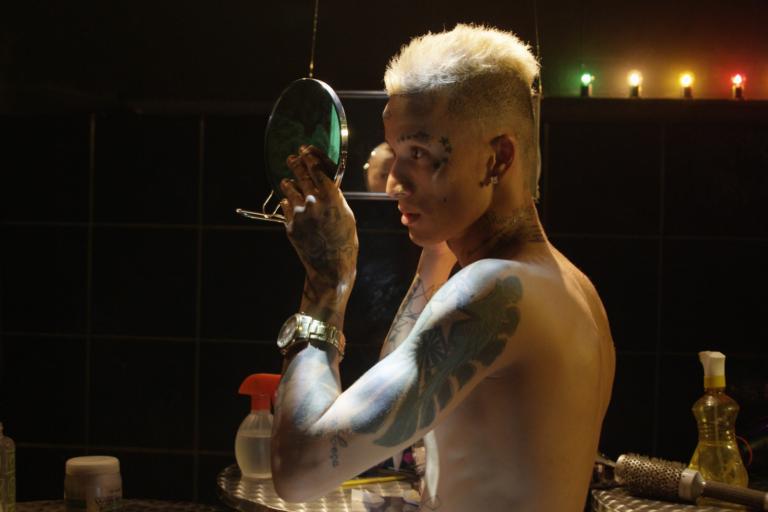

a couple years ago, i came across a video piece by the artists bárbara wagner and benjamin de burca, estás vendo coisas (you are seeing things), that surprised me with its unique manifestation of a genuinely brasilian subculture. the video follows two performers, mc porck and dayana paixão, as they negotiate the labor of their everyday lives alongside aspirational careers in pop music; porck is a hairdresser by day and a brega-funk rapper by night, while paixão is a firefighter and a brega-romântica-singer.

the video utilizes the aesthetics of brega, a brasilian music style somewhat similar to american kitsch. this style was originally geared towards the masses, and due to its humble roots, brega’s critics saw it as a synonym for tacky taste. the video also delves into the culture of frevo dance and music but subverts it through gender fluidity and technology that has only recently become more accessible in brasil.

wagner and de burca met in the netherlands through a friend while attending the dutch art institute in arnhem. they started working together, documenting the culture of poorer communities in recife, brasil, where wagner is from; de burca is german-irish. the pair were chosen to represent brasil at the 2019 venice biennale. the video work they presented, swinguerra, brought into the international arena a slice of brasilian culture that has long been under threat, and even more so during the country’s current reactionary political climate. the young dancers in the cast are brown and black — some are transgender and generally serving non-conformist looks. they belong to troupes that “battle” through dance for visibility and an opportunity to transgress their social backgrounds.

back in may 2020, while sitting through a covid quarantine, i spoke with the duo who were in berlin preparing to shoot a new work for the manifesta biennial in marseille. the work, titled one hundred steps, would take shape by focusing on cultural parallels between irish and marseillais cultures while celebrating the work of documentary filmmaker bob quinn.

while researching irish sean-nós (old style) singing and dance for this new piece, they met quinn and learned about his atlantean quartet of documentary films and accompanying book which question the myth of ireland’s purely celtic origins. in these works, quinn traces irish roots back to northern africa, revealing similarities between sean-nós singing and dance practices found in morocco and egypt.

the transformation of culture, as it morphs through generations, is an undercurrent in wagner and de burca’s body of work. in ireland, the artists attended festivals where young people keep cultural traditions alive by building on forms such as lilting singing (which has similarities to american scat). wagner likens this reinterpretation of tradition to what she and de burca observed when researching frevo’s trajectory in brasil for their 2015 video faz que vai (set to go), which features four frevo dancers in recife. in its customary representation, frevo has had very delineated gender roles. in this piece, however, the artists queer up these divisions using various performers that don’t conform to this standard.

“coming from the northeast of brasil, with roots in capoeira,” wagner says, “frevo was a form of dance and music that gave an account of the slaves’ resistance. at the beginning of the 20th century, it became a form that was slowly connected to celebrations during carnivals. in the 70s, its visuals became imagery used on postcards to represent folkloric traditions in brasil. so, we were continuing this research on how various traditions get to be refashioned by younger generations while producing the culture of today…

“they are a generation of artists that have had access to technology only very recently, mostly in the past fifteen years because of the economic growth in brasil during this time. that had a big impact on how people produce art. we are interested in looking at how resistance to a traditional mainstream is actually found in the bodies of these people who are changing it with technologies and through learning from other forms of culture that are global, and completely pop.”

wagner and de burca’s works employ the structure and language of the music video genre. wagner explained that one of their driving motivations in making the work is the desire to collaborate with artists using popular forms that could easily be dismissed as unsophisticated. they want to find ways to represent these artists and open up possibilities for them to be seen in different contexts.

in their 2019 video terremoto santo (holy tremor), the duo worked with members of a new brasilian evangelical movement that recruits youth from low-income rural communities by offering them a means of social ascension through religion. their 2018 work rise features a group of mostly caribbean and african immigrant spoken word poets in canada. bye bye deutschland, eine lebensmelodie, made in 2017, chronicles the lives of steffi teumner and markus sparfeldt, two club singers and performers of schlager, a german working-class pop genre that has sentimental and nationalistic overtones.

in describing their work, the artists suggest that what is being put forth are “sketches of presentation formats for artists that work in different music industries and are responding to economic change”. the music video format, with which the duo has molded its practice, provides an alternate frame for these popular music manifestations by transposing the performers onto different settings. for example, in rise, the performance space is moved to subway stations, a space used by the performers daily as a means of transportation. in the video, the stations become their stage.

wagner and de burca’s videos typically showcase people of color, fluid in gender, and from unprivileged communities. this has led some critics to question whose point of view is being projected through their work. with de burca being a white male from a european country, one can wonder what it means for the pair to engage with their chosen subjects and themes. they explain to me that the position they assume is not to “represent or bring these artists to light. it is a collaboration… these artists are already connected and distributing their own work into the world. they already yield a certain power through their practice. we bring a proposition of how to collaborate in the music video format. during this collaboration, there is at first a conversation about their work: its performance, distribution and audience. and then we talk about how to displace the practice to create something new collaboratively.”

during our conversation, i brought up the relationship of their work to ‘subcultures’. the artists feel a certain ambivalence towards this term. they think it needs to be carefully considered when used in the brasilian context. in the portuguese language, the prefix ‘sub’ means a form of subjugation, denoting hierarchical inferiority. from this standpoint, a subculture seems to describe something below the prevalent culture instead of directly conversing with it. in anglo culture, however, the word alludes to space with ample possibilities for subversion. this means it can often be seen as a highly desirable description that validates certain types of more transgressive cultural manifestations.

furthermore, my describing the performers in some of the videos as being from “poorer” socio-economic backgrounds seemed to bring about a reluctance on their part. as a brasilian, i attribute this unease to the perennial insistence in the first world on looking at our culture through a third-world lens that fetishizes poverty. this creates a stigma that can be stifling to culture-makers. one can see that, given the option, artists would prefer to discuss facets of their subjects other than the dead horse of economic background.

the ongoing creative exchange between these artists and the performers in the videos propels the energetic power of their body of work. by transposing these different practices onto visual platforms of their own making, wagner and de burca exalt and reposition these performers, giving them alternative spaces in which other layers and readings of their work can materialize.