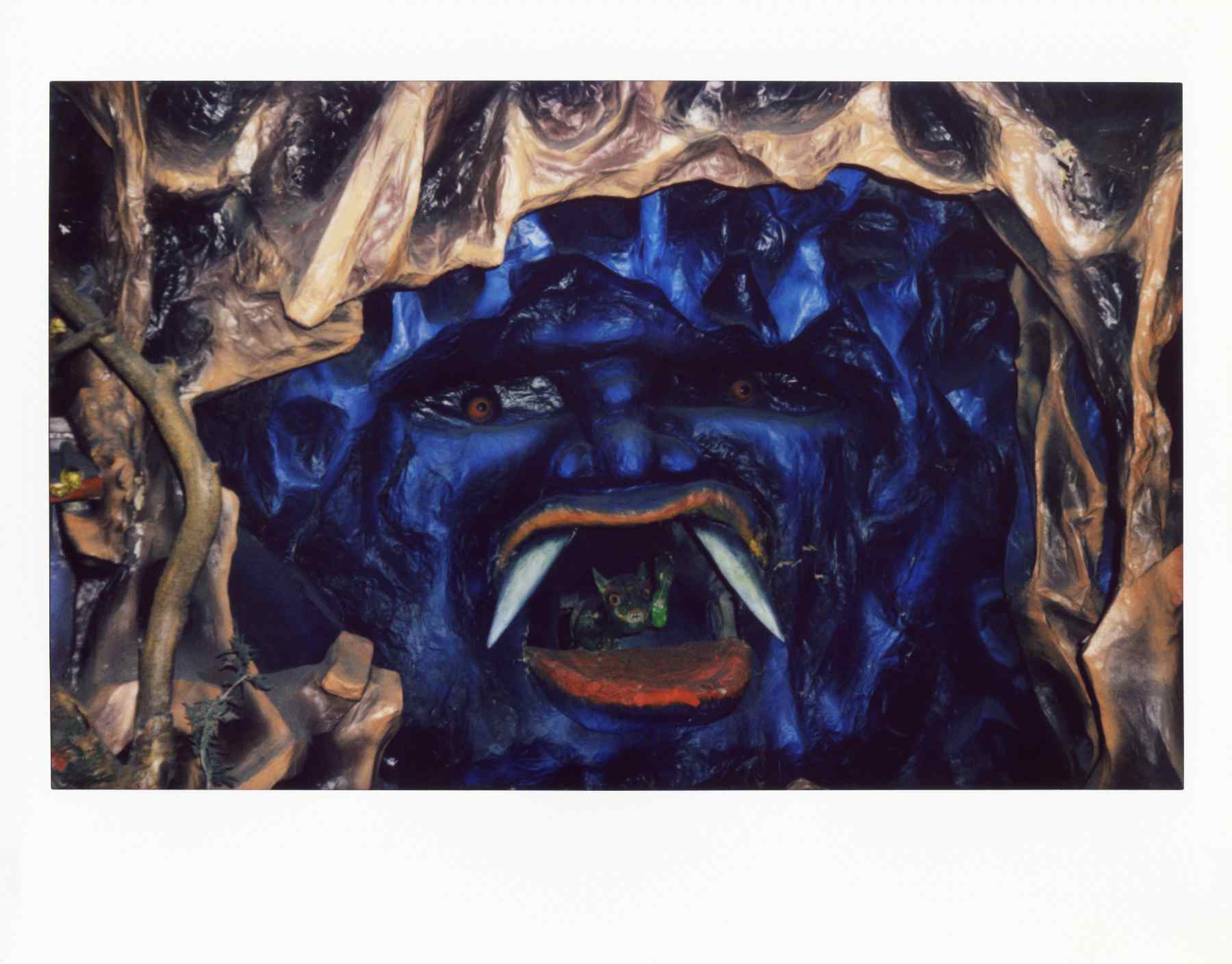

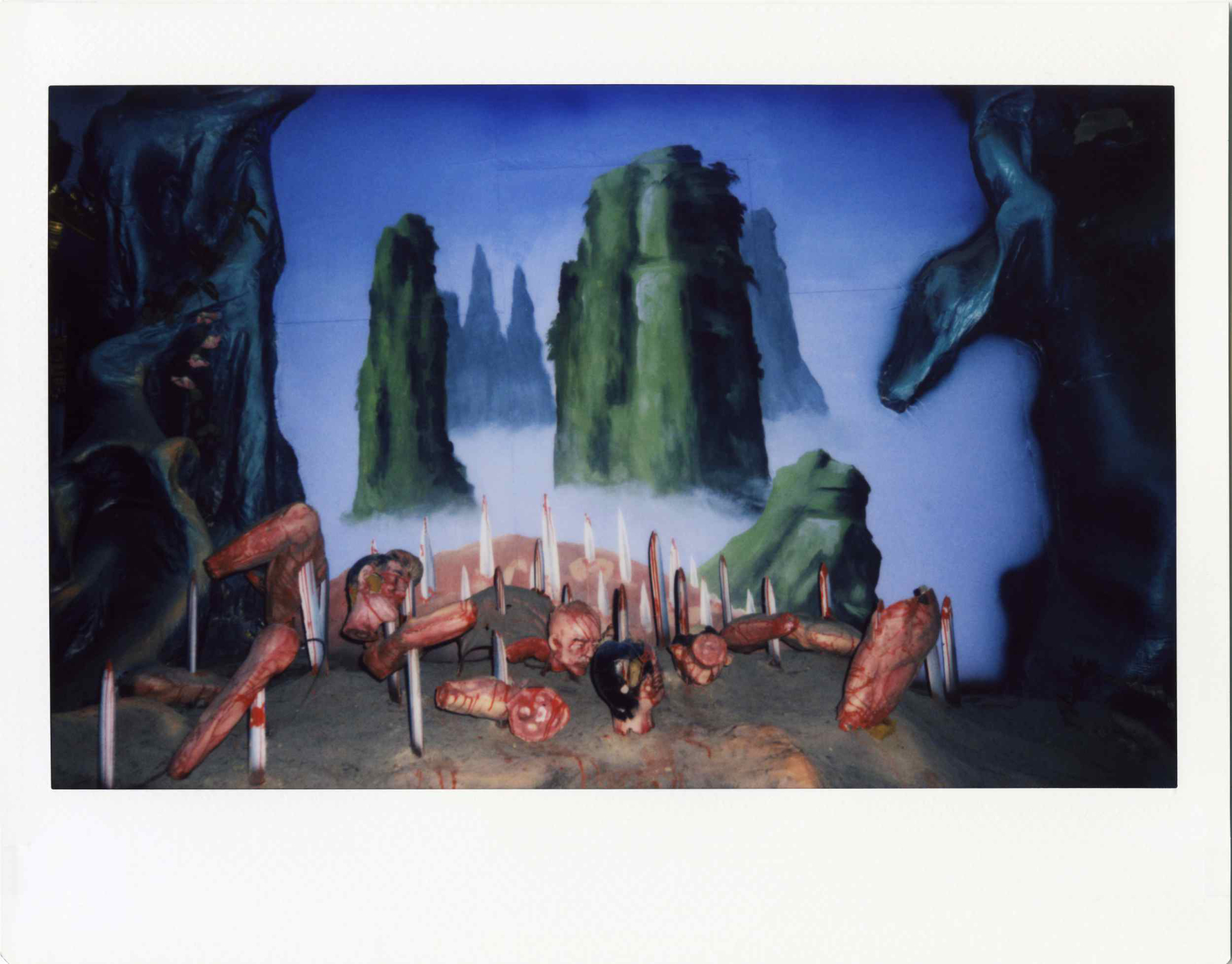

Tainan, in southern Taiwan, is home to one of the island’s more idiosyncratic entertainment and religious narrative displays. In the basement of Madou Daitian Temple (Temple of Heavenly Viceroys), one may encounter—if they desire—an animatronic rendering of Chinese mythological hell. In this transitory purgatory, sinners atone for earthly misdeeds before being recast into the world anew. Unfolding across eighteen gory levels, each realm enacts its own distinct form of brutal cosmic justice.

Such gruesome and enthralling portrayals of the underworld—whether in the form of tourist attractions, pulp fiction, temple scrolls, paintings, or ancient literature—have been a popular genre since tenth-century imperial China. Combining elements of Buddhist and Daoist theology, Indigenous Chinese spirit worship, and traditional storytelling, a new conception of hell emerged in the medieval period. This vision continues to shape interpretations of the underworld across much of Asia today.

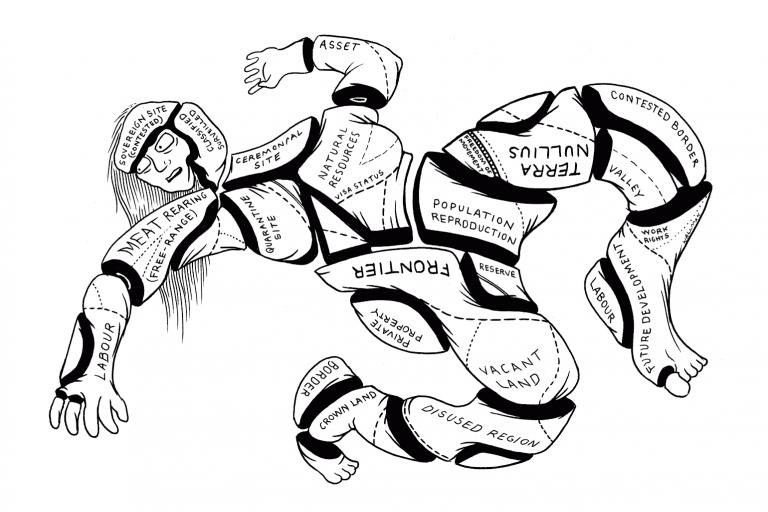

This subterranean system mirrors the structure of the Chinese imperial bureaucracy above, with its courts, officials, and legalistic proceedings. In its dark recesses, a fiendish staff operates the wheel of karmic justice—an unseen, shadowy authority in the depths of the netherworld. All lost souls must proceed through its labyrinthine judicial halls, submitting to the vicissitudes of its judgments. Knowledge of the system’s workings comes from near-death experiences, in which those summoned escape its clutches and reemerge with a warning for humanity. Yet these moralizing accounts, intended to foster virtue among the citizenry, belie a nightmarish vision of unchallenged power.

A modern incarnation of this genre is the Taiwanese book Voyage to Hell by Yang Zanru. The popular novel was created through a succession of seances involving planchette automatic writing at the Sheng-Xian temple in Taichung between 1976 and 1978. In these sessions, Yangsheng, the novel’s protagonist, is guided through the underworld by his master, Tse Kong, a 12th-century Buddhist monk believed to possess supernatural powers. During these journeys, Yangsheng witnesses the hellish precincts first-hand, interacting with their bureaucratic authorities and many of the incarcerated. The tortured souls he encounters describe their terrestrial sins and beg Yangsheng to petition the authorities for leniency in their cases.

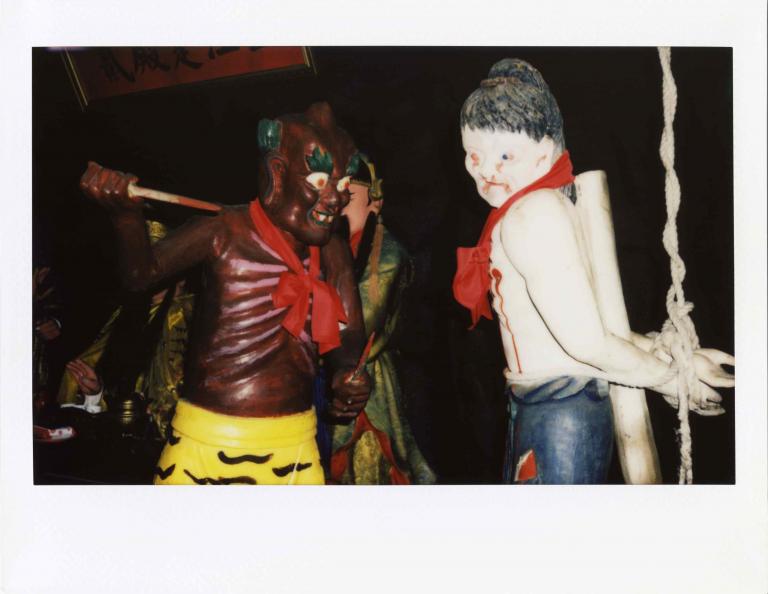

In one scene, a general escorts Yangsheng and Tse Kong to the Eyeball Wrenching Prison, where Yangshen recounts painstakingly what he observes: “The inmates of this prison all have their eyeballs extracted from their sockets,” he describes, “and blood is streaming out. One after another, they cry and howl bitterly, closing the hollows of their orbits with their hands...

“To the left, a guard, with his spear, is perforating the orbit of a middle-aged man and wrenching out his eyeball. The victim tries to dodge aside vainly, and the eyeball of his left eye is extracted and drops on the ground. He utters a muffled shriek, his soul in delirium, his body sagging, his head bent forward. He faints but can’t fall down, being tied fast to a stake. The guard, impassively, is preparing to extract his other eyeball. I feel out of breath at this sight! That’s barbaric.”

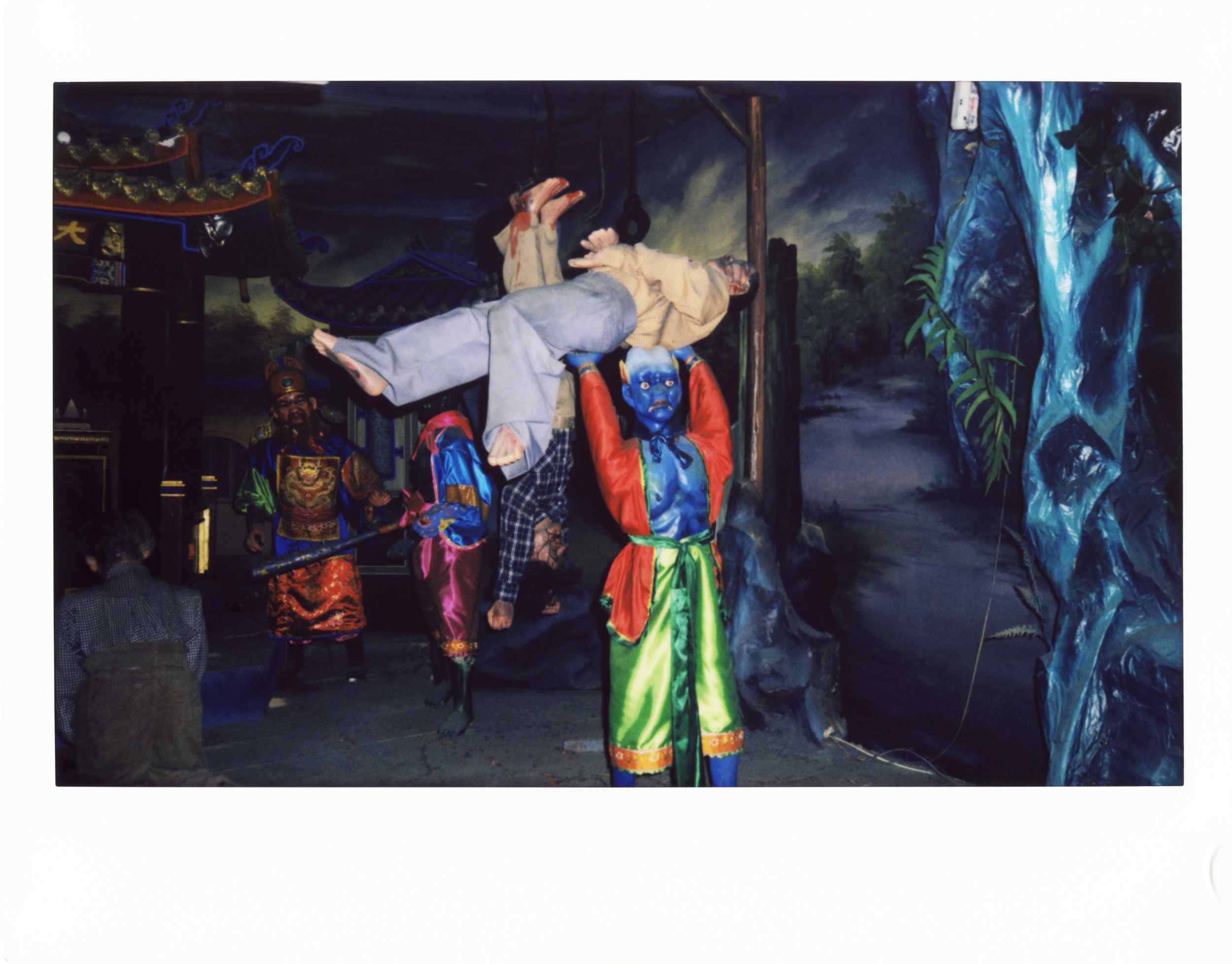

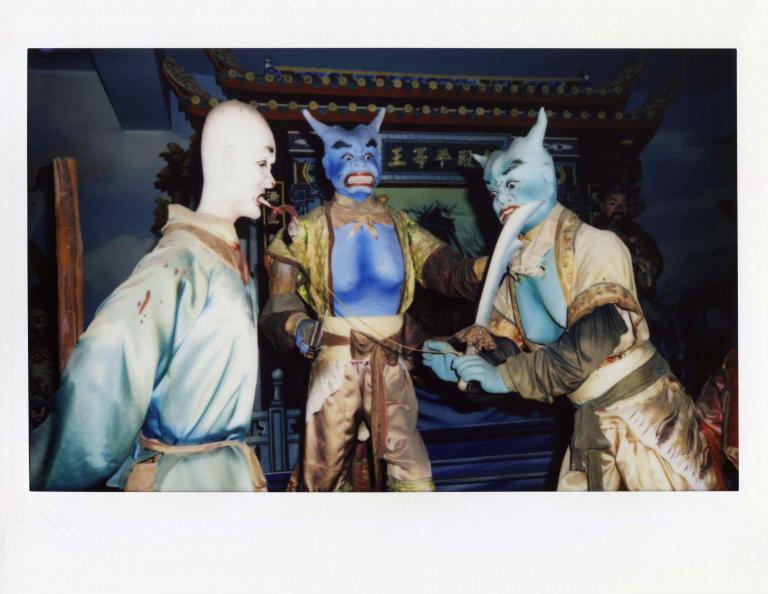

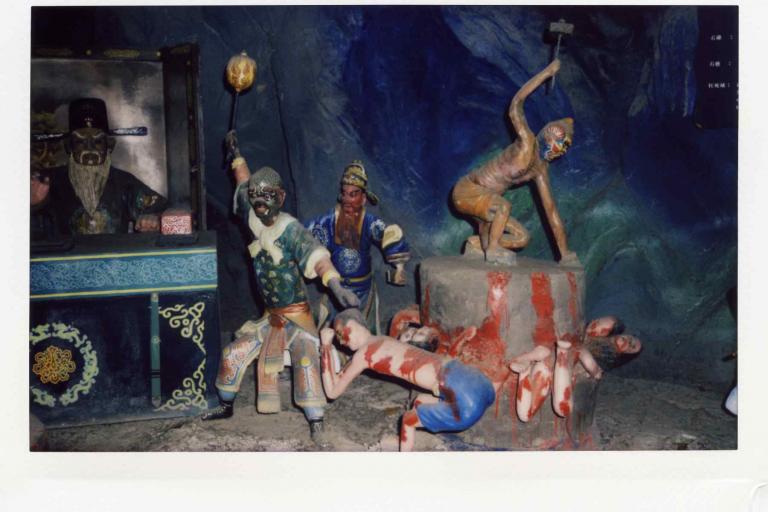

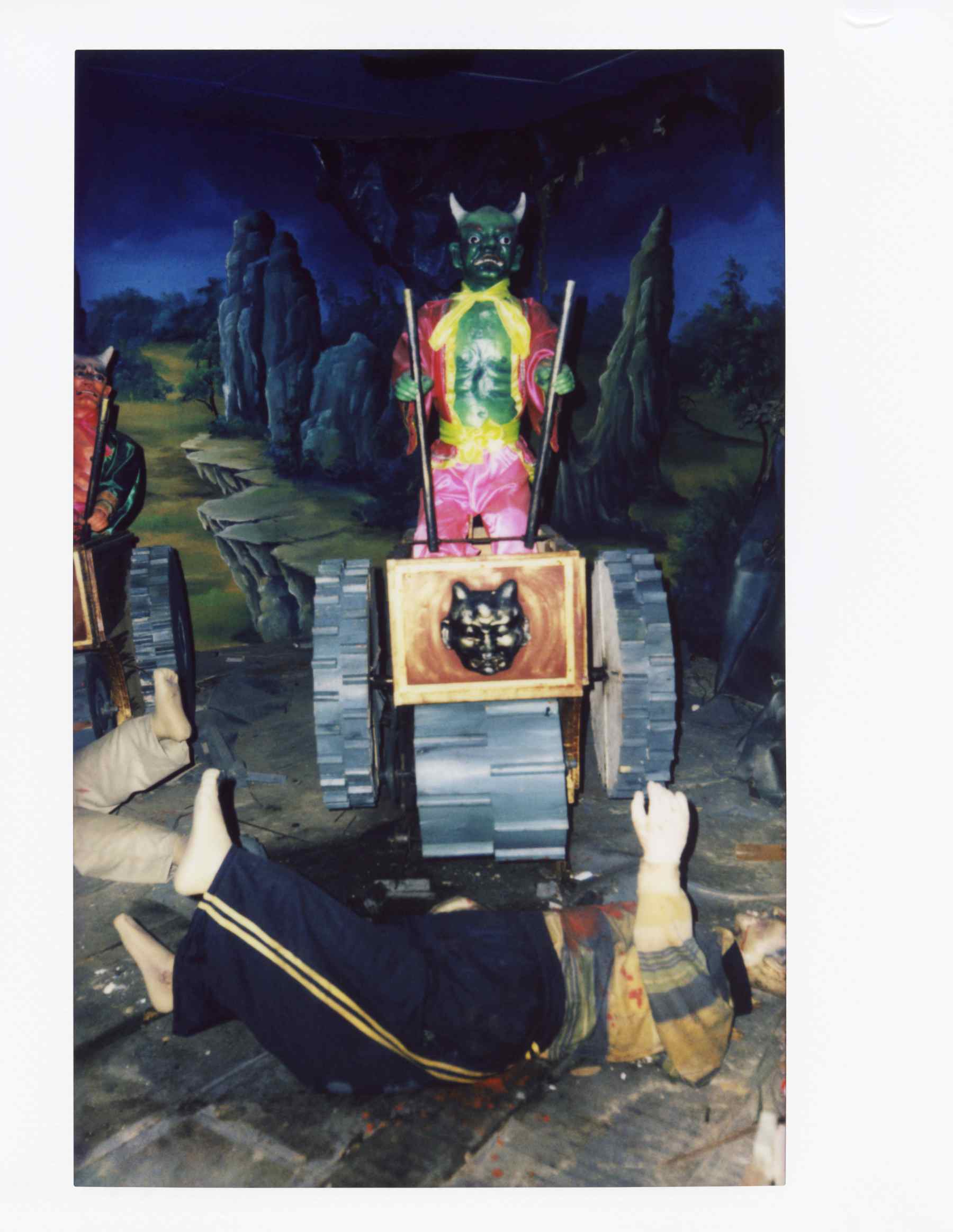

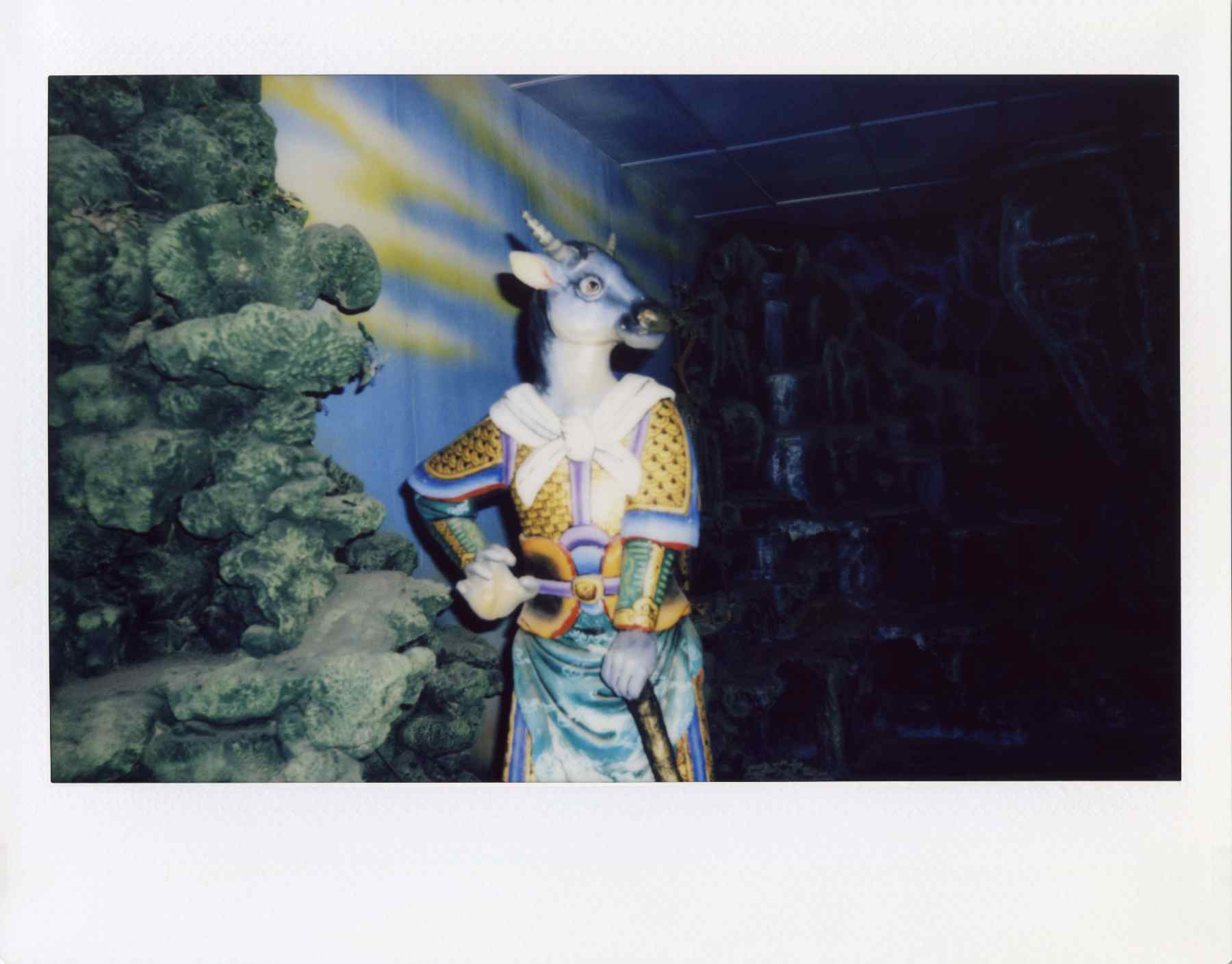

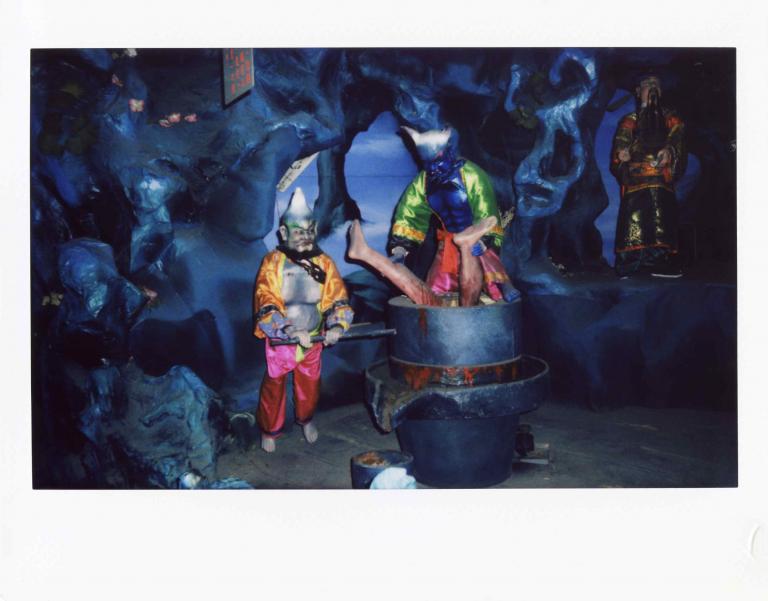

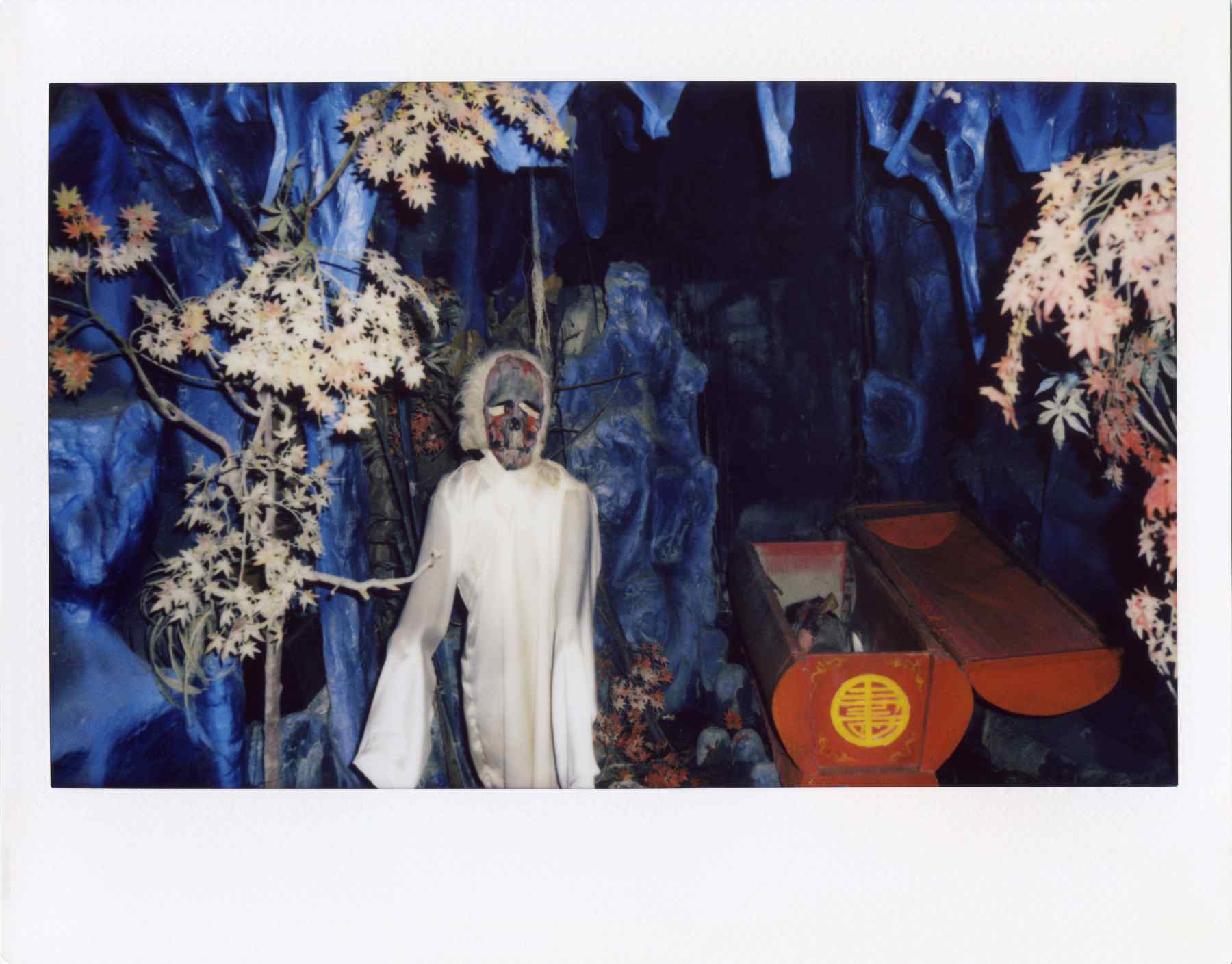

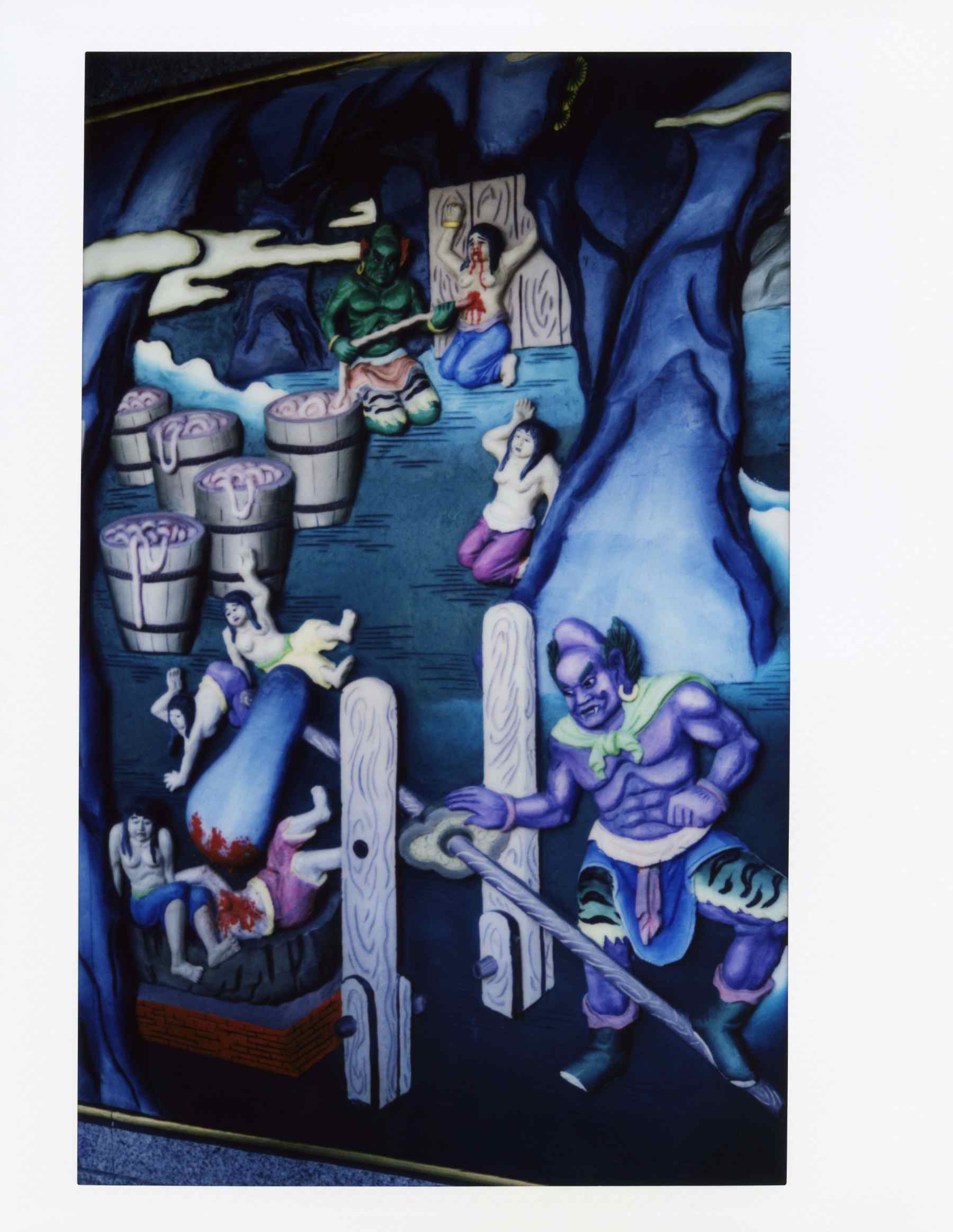

Narrative scenes of hell play out at temples across Taiwan, but none as visceral as Madou. Plucked from the world of the living, the souls of the deceased are captured and hauled down into the underworld by the black and white deity generals, Fan and Xie. During the opening judicial proceeding, each soul is interrogated by the first Lord of Hell, accompanied by his ox-headed and horse-headed secretaries. Each confessor is confronted with the karmic Mirror of Retribution, thrust before their face to reveal inescapable misdeeds. The righteous and the innocent receive safe passage to heaven, while the guilty are assigned to the appropriate courts. Some particularly wretched individuals must endure the full spectrum of torment.

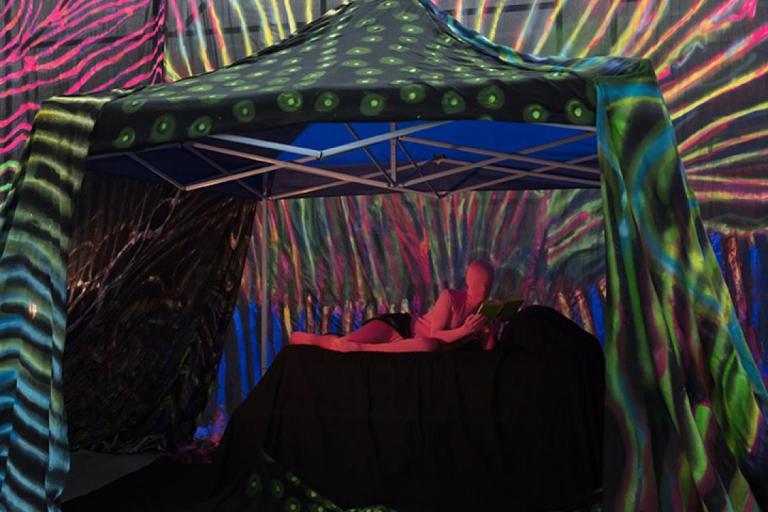

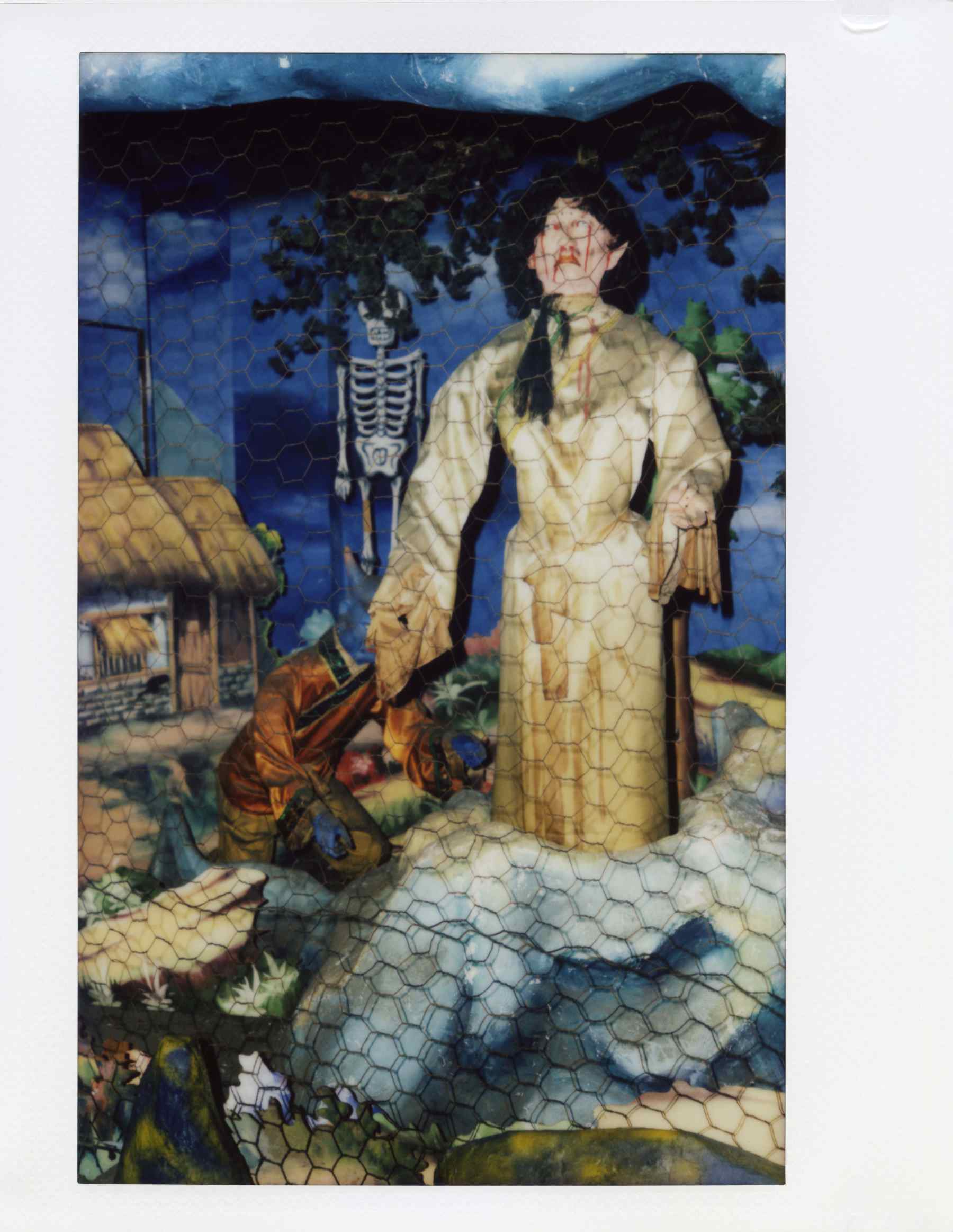

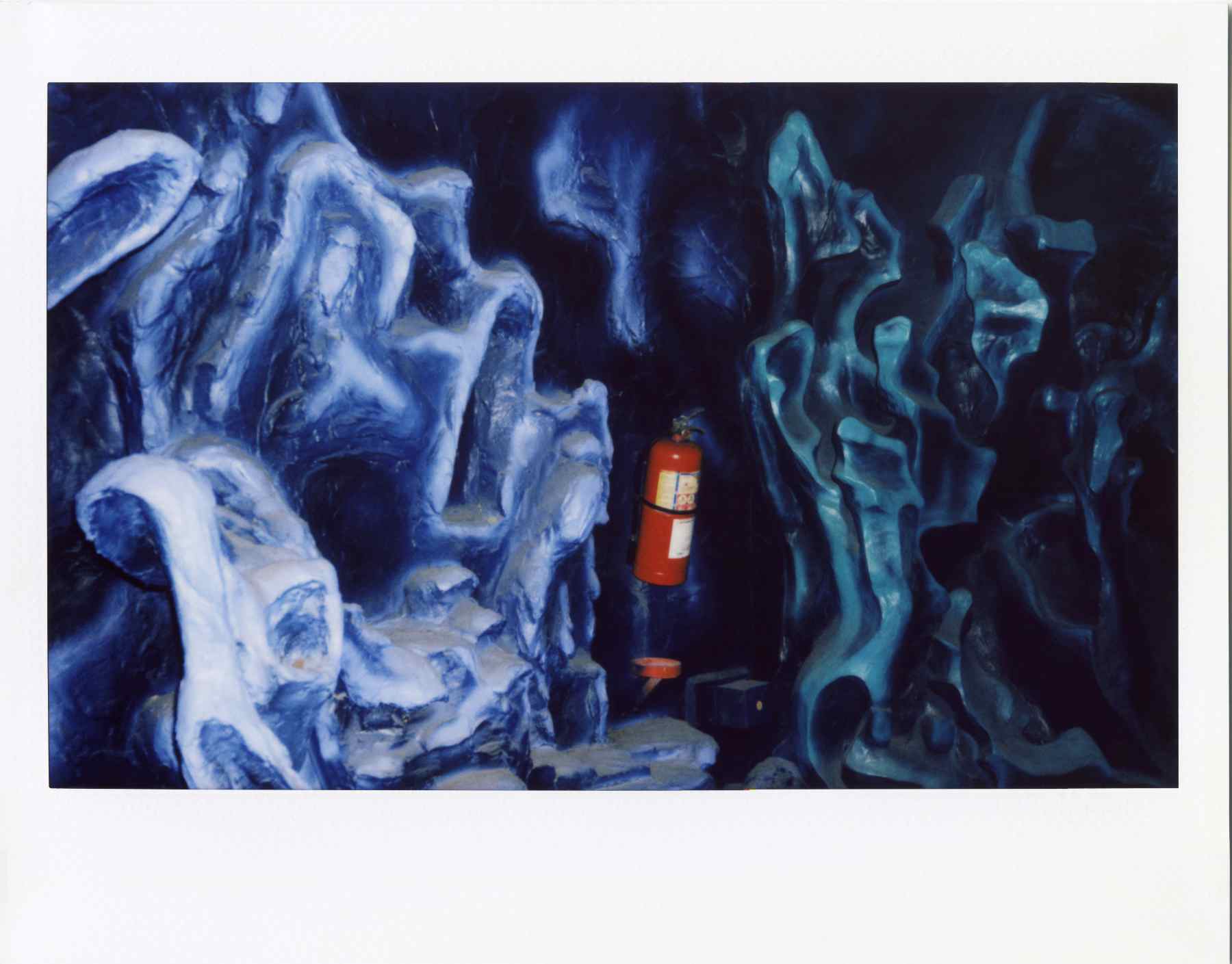

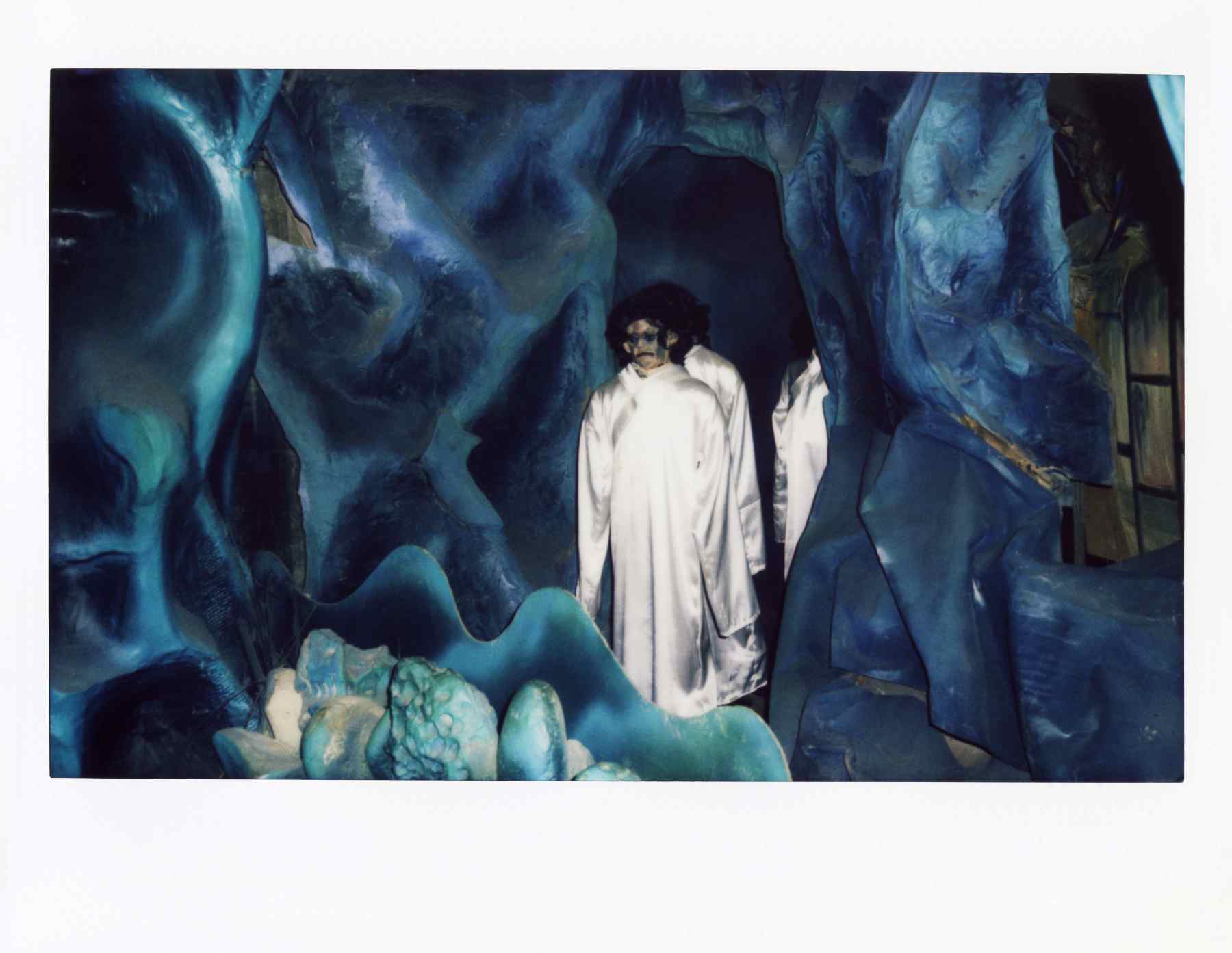

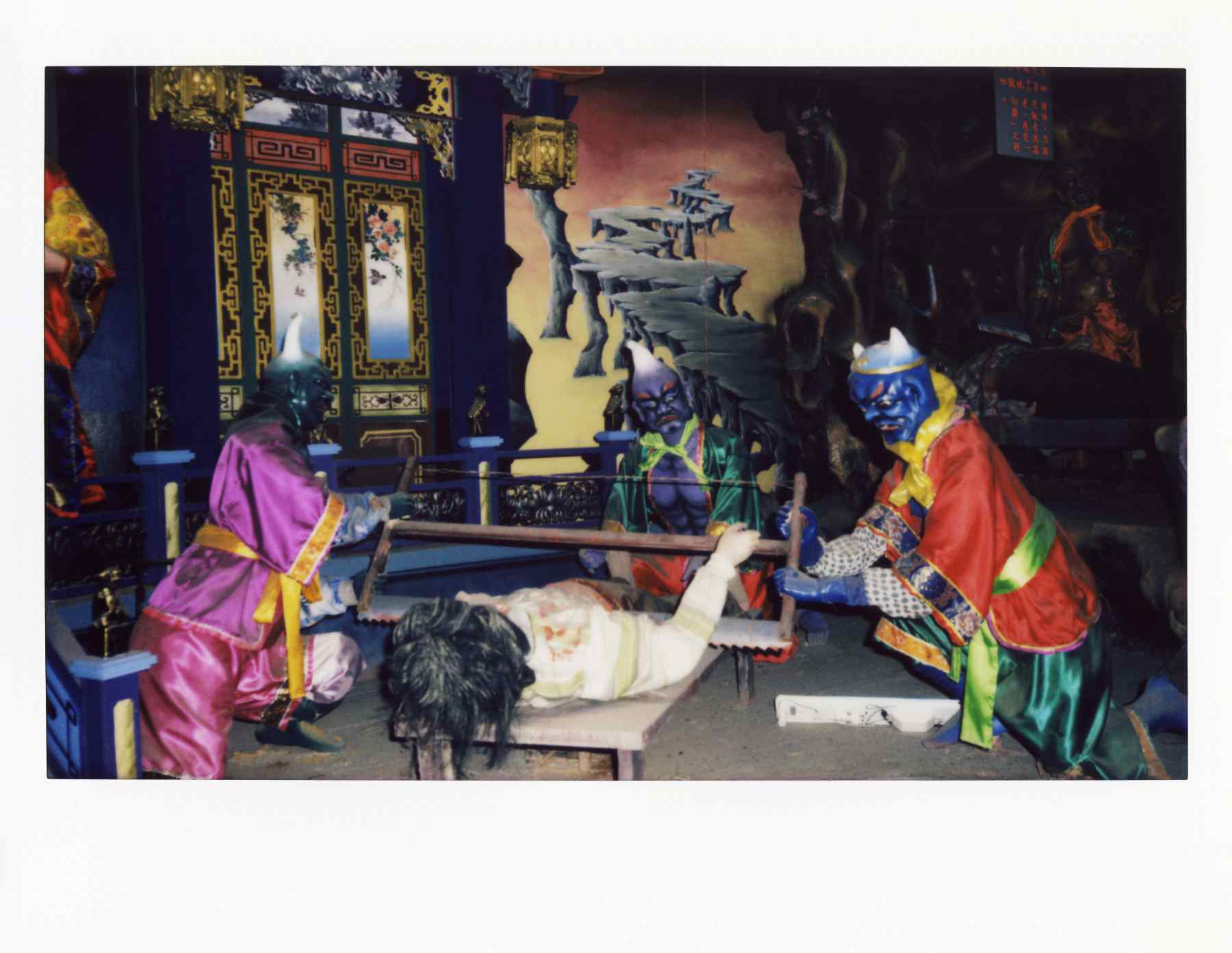

Walking through the dark passages of Madou, we are confronted with a procession of spine-chilling court scenes. Dragged before the judges of Madou’s infernal chambers, each bedraggled figure falls to their knees, desperately pleading for mercy. We are not spared the gruesome details of the resulting punishments. Motion sensors trigger shrieking, staticky tape loops as children wail, clinging desperately to their mothers. Others stand stoically transfixed.

Punishments are meted out specific to the crime. Those who have told lies, for example, shall have molten lead poured down their throats, searing their insides. Through a slow, excruciating process, a murky pool of guilt is refined into a transmissible narrative product. As Charles D. Orzech explains in his article, “Mechanisms of Violent Retribution in Chinese Hell Narratives,” “Information is the excuse, not the goal of torture.”

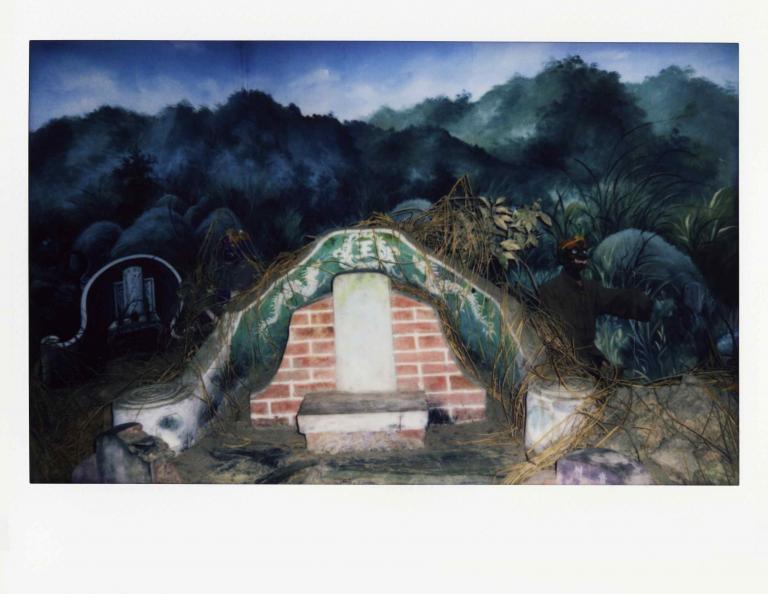

Above ground, in the world of the living, priests, monks, nuns, folk practitioners, and various mediums attempt to “grease the wheels of bureaucracy with their ritual knowledge and with community offerings to obtain release for imprisoned souls.” The lords of hell are not above accepting bribes—received through the burning of ghost money—and there is an uneven efficacy to these rites of karmic retribution. The infernal bureaucracy is known for its occasional bungling, yet the wheels of justice grind on.

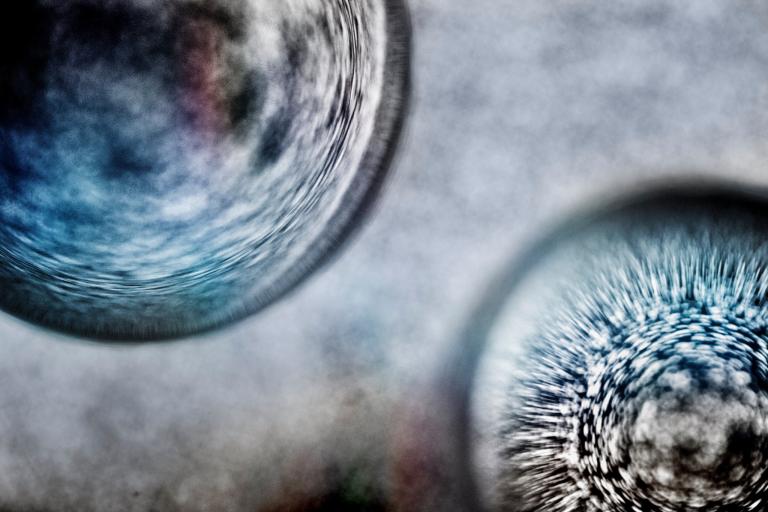

All souls of mortals, upon death, must pass through the underworld, but this is purgatory, not eternal damnation. At the final level of hell, the wheel of fortune spins, assigning each soul to its next life vessel—whether human, insect or another animal. Meng Po, the goddess of oblivion, offers each mortified being a cup filled with the Broth of Oblivion, a powerful elixir that erases all memories. Upon drinking this celestial potion, all is forgotten, and the cycle of life continues.

Emerging semi-dazed from the depths of hell, a visitor to Madou may then choose to ascend into heaven, housed in the body of a giant green dragon. But relatively speaking, this is a mundane affair, offering more of a calm-down after the pitches of intensity experienced in the underworld. Clearly, hell is the main attraction.

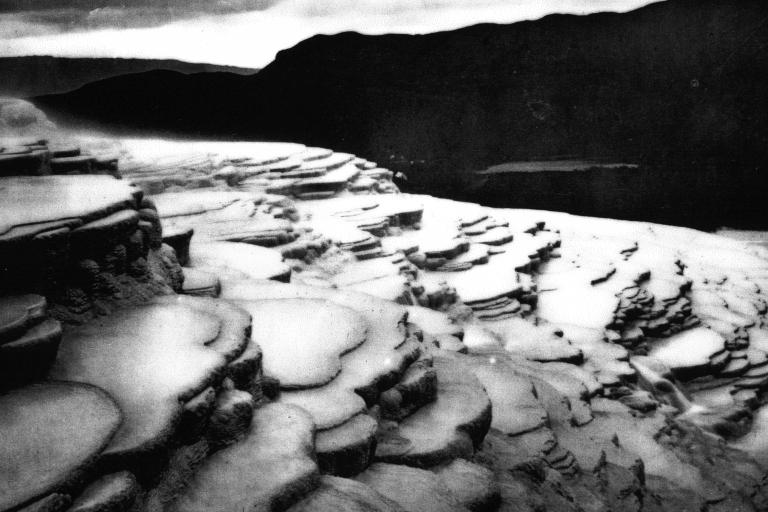

In this series of wide-angle Polaroids, Yao Jui-Chung captures Madou Daitian Temple's animatronic religious display and other similar depictions of hell throughout Taiwan and Singapore. These images continue the artist’s photographic treatment of Taiwan’s religious statues, decaying buildings, temples, and amusement parks. Texts describing various punishments, directly taken from signs hanging within the Madou Temple display, accompany the works.

SIXTH LEVEL OF HELL: DRUG DEALERS, MAKERS OF ADULTERATED PHARMACEUTICALS AND WINES WOULD BE FRIED IN CAULDRONS OF OIL.

SEVENTEENTH LEVEL OF HELL: RUMORMONGERS, THOSE WHO MAKE FALSE ACCUSATIONS, AIDERS AND ABETTORS OF MANSLAUGHTER SHOULD HAVE THEIR TONGUES PULLED OUT AND THEIR CHEEKS GORED.

THIRTEENTH LEVEL OF HELL: WOMEN WHO WILLFULLY DISOBEY THEIR MOTHERS- AND FATHERS-IN-LAW WILL BE CRUSHED BY GIANT ROCKS/BOULDERS.

EIGHTH LEVEL OF HELL: THOSE WHO CUT CORNERS WITH ILLICIT MEANS FOR SELFISH GAINS SHOULD BE EATEN BY PREDATORS AND SNAKES.

THIRD LEVEL OF HELL: THIS IS RESERVED FOR THOSE WHO ARE DERELICT IN THEIR PROPER DUTIES AND BULLY THE DEFENSELESS. THEY ARE PUT INTO A GRINDING MACHINE AND GROUND INTO A BLOODY PULP.

ELEVENTH LEVEL OF HELL: THIEVES, KIDNAPPERS AND CON ARTISTS ARE PUT INTO A GRINDING MACHINE AND GROUND TO A BLOODY PULP.

TWELFTH LEVEL OF HELL: THE FOUR LIMBS OF BANDITS, MURDERERS AND HIGHWAYMEN ARE SAWED OFF.

SECOND LEVEL OF HELL: CORRUPT OFFICIALS WHO ABUSE THEIR POWER AND TORMENT AND BADGER THE PEOPLE SHOULD BE DECAPITATED IN THE "TIGER HEAD" TORTURE.

FIFTEENTH LEVEL OF HELL: SWINDLERS OF MONEY AND THOSE WHO CAUSE THEIR VICTIMS TO COMMIT SUICIDE THROUGH DROWNING OR HANGING SHOULD BE TORTURED WITH DISEMBOWELMENT BY HAVING THEIR GUTS CUT OPEN AND BOWELS REMOVED.

EIGHTEENTH LEVEL OF HELL: AFTER SINNERS DRINK MENG PO'S "TEA OF OBLIVION", THEY ARE GIVEN A CERTIFICATE TO RETURN TO THE WORLD OF MORTALS IN THE FORM OF AN INFANT THROUGH "SA SĀRA".