Slavs and Tatars didn’t intend on becoming artists. The Berlin-based collective began in 2006 as a book club which grew into a project involving publishing, lecture performances, installation, and exhibitions. The work, all intended to bring audiences back to the book, revels in complexity, challenging simplistic attitudes towards the region east of the Berlin Wall and west of the Great Wall of China. In this burgeoning oeuvre, heavy in satirical humor and steeped in research, one finds no clash of civilizations between east and west. Rather, one encounters a proliferation of affinities and internal contradictions. Slavs and Tatars bring together mutually exclusive and antithetical thought in a process they describe as “doing the metaphysical splits”. Privileging the paradoxical nature of identity, the collective operates anonymously. The emphasis is instead on the subjects of the work. Nicola Trezzi interviewed the collective about their unusual practice.

Nicola Trezzi: Slavs and Tatars began as a book club in which you translated rare texts and shared them among a circle of friends. But from there, you found your way into the art world. Despite the wide array of publications, exhibitions, and lectures that have since transpired, you say that everything is intended to bring people back to the book. How does that beginning as a book club, as a shared learning process, underpin the Slavs and Tatars project?

Slavs and Tatars: There isn’t a clear hierarchy in a book club, unlike a traditionally pedagogical setting such as a class or seminar. So, the flattened horizontality allows for a sense of generosity, intimacy, and participation which has characterized our work. In the name alone — Slavs and Tatars — as with the geographic remit — between the former Berlin Wall and Great Wall of China — are hints of this: It’s impossible to be specialists of such a landmass.

NT: You say that the art world has enabled you to produce publications that would not have been realized elsewhere. But given your contrarian nature, I presume that you also have a critique of the art world itself. How easily does the Slavs and Tatars collective sit in this world?

S&T: We very much considered ourselves outsiders until 2016 or so, when we traveled with a mid-career survey to various venues in Warsaw, Tehran, Istanbul, and Vilnius. It dawned on us that we needed to assume the responsibility that comes with a certain maturity and body of work. Since then, in addition to the three axes of our own practice — the books, exhibitions, and lecture performances — we’ve been pursuing several initiatives to reclaim Slavs and Tatars as a platform, as opposed to simply being an artist collective. That is, to continue to investigate those ideas we’re interested in, but via other people’s practices. We launched a mentorship and residency program for young professionals from our region in 2018 with residents thus far from Minsk, Yerevan, Tbilisi, Khabarovsk, and Istanbul. And a couple of months ago, we launched Pickle Bar, a Slavic aperitivo bar cum project space where we invite thinkers, writers, performers, and artists to address the limits of the tongue both affectively and discursively.

NT: Slavs and Tatars has been prolific as publishers and publications comprise a major component of your output, yet you maintain what you refer to as a “healthy suspicion” of print. Can you elucidate your complicated view of this medium?

S&T: We’re interested in redeeming the collective nature of reading in the literal sense. For most of its history, paper and the written word have been destined to be read to a crowd or public. Of course, there’s the liturgical/scriptural element in this, be it the Kabbala or the Qur'an. Text is meant to be performed, whether read internally, rocking back and forth, or recited. But also, in a more figurative sense: the act of reading as constitutive of a civic body.

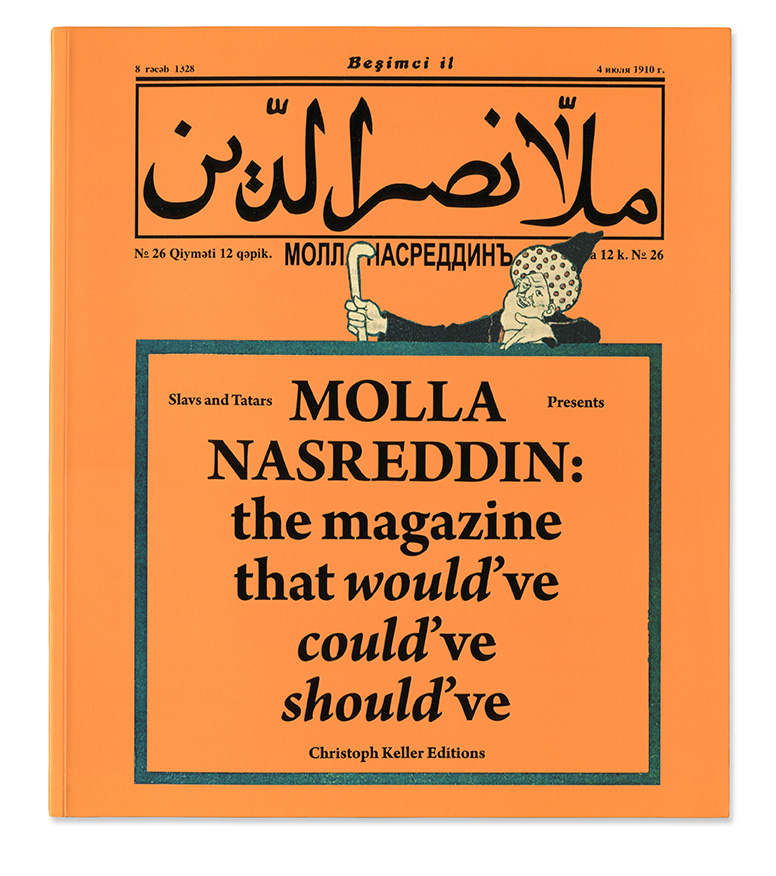

NT: You spent two years translating the early 20th-century satirical Azeri magazine Molla Nasreddin. While the publication is known for its promotion of women’s rights and its anti-colonial stance, it also pushed forward views that you strongly disagree with: The publication called for Western-style modernization and blamed Islam for what the editors viewed as the growing gap between the Western and Islamic worlds. Why did you dedicate so much time to translating a publication which disseminated views that clash so starkly with your own?

S&T: To some extent, Slavs and Tatars was created for this very purpose. To explore bodies of knowledge — digestive, affective, metaphysical, or simply analytical but geographically other — beyond the canons of universities, cultural institutions, and media to which we’re accustomed and have access. Now, affinity is not necessarily a useful or healthy ingredient when it comes to learning or edifying oneself. Au contraire, we should engage further with those ideas, belief systems, and people we might first find distasteful.

NT: Your 2018 lecture “Red-Black Thread” at Walker Art Center in Minneapolis was a fascinating look at the construction of Black identity through the Soviet Union. This was an unexpected window into current events and a challenge to what you call the “Atlanticist perspective” of blackness. When the 3rd Communist International took place in 1919, an explicit commitment to anti-racism and the liberation of African nations was written into its charter. Was this more than propaganda?

S&T: Yes and no. As the Russians would say, да-нет. It had significant, concrete importance for PoC: It was the first instance in history of a multiethnic state defining itself as anti-imperial. Not to mention the first Socialist state, which had very symbolic importance for an African diaspora whose lives are defined by the exploitation of labor. So, whether it was done in sincerity or as a political strategy casts doubt over a crucial part of the population it affected.

NT: Slavs and Tatars is dedicated to focusing attention on geographies, histories, and cultures that are often overlooked and a heritage that is under siege, so it may come as a surprise to some that you hold a critical view of multiculturalism and consider it to be a neoliberal construct. You say that coexistence does not necessarily need to be thought of as conviviality or harmony. Perhaps we shouldn’t take those concepts at face value. Is there more to ‘harmony’ than meets the eye? How else can we think about coexistence?

S&T: We’re deeply critical of the individualist bent and emphasis on victimhood which defines much of identity politics. We’re not against multiculturalism any more than we’re against the Enlightenment. It’s simply important to see the limits of the concept and consider alternative scenarios. Otherwise, it is easy to fall into the binary, reductive thinking which blights our times. Was the Soviet Union a colonial enterprise? Well, yes and no is the uncomfortable answer. The ability to hold contradictory truths or claims, live with them, and understand their complexity is a sign of intelligence that is desperately needed today. So, coexistence is not rosy, and it sure as hell ain’t homogenous: It can and perhaps should include tension and channels for conflict to be resolved without resort to violence.

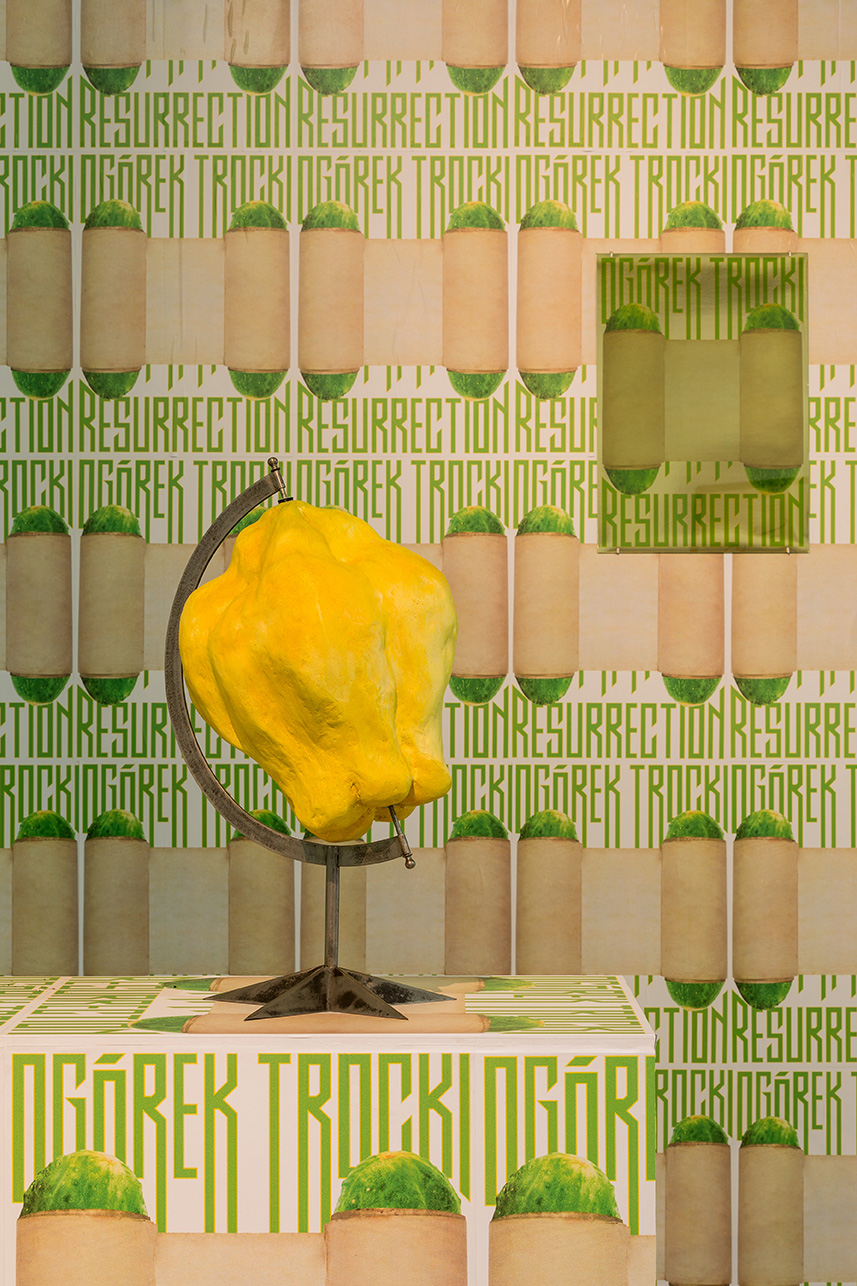

NT: In recent years your work has dealt with pickles. The microbe and bacteria, you say, can be thought of as the original foreigners. Can you tell me about your fascination with fermentation?

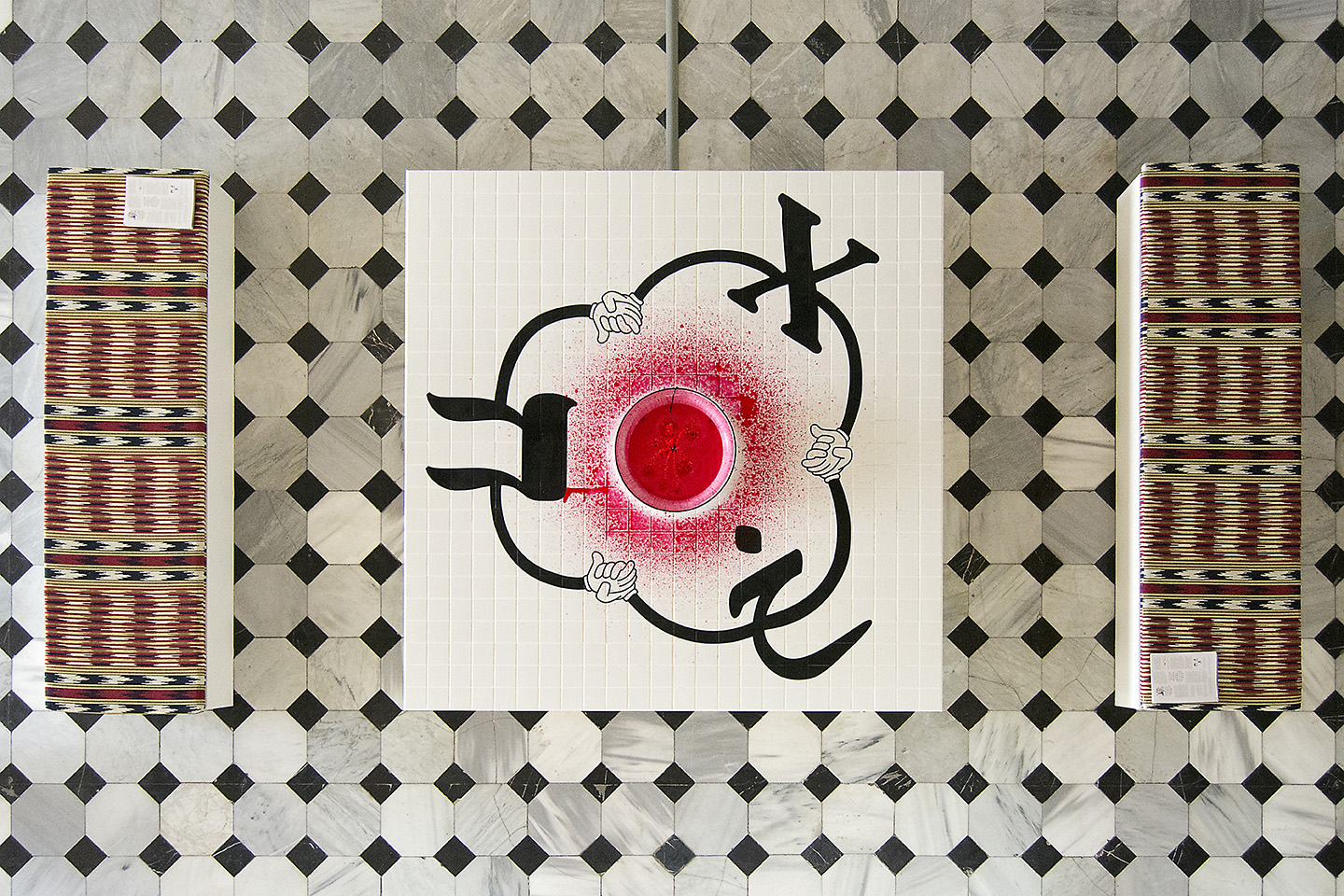

S&T: Fermentation is what we call a “stupid medium”: a seemingly anodyne, pedestrian, often low-brow means through which we can unravel complex issues. We’ve resorted to such media in the past with balloons (Monobrow Manifesto, 2010-11), swings (PraySway, 2015,) amongst others. In our “Pickle Politics” cycle, it’s cucumbers or cabbage in saltwater or salamoia [brine], associated with babushkas and a certain rustic way of life. Yet in fermentation, we see nothing short of the challenge to the Enlightenment and its insistence on binary oppositions. Fermentation scrambles this dynamic in so far as it preserves through a managed or controlled form of rotting. In fact, bacteria play this double part in being both beneficial and dangerous. Ever since Louis Pasteur [the inventor of pasteurization], we’ve had a tendency to overemphasize the dangerous aspect.

Thanks to Natalia Filimonova and ZETTAI for their collaboration in producing this article.