The scene opens in a loft in lower Manhattan. It is light and airy with paintings and sculptures, including three by Max Ernst, on display. Through one window, the Atalanta building can be seen. Books on travel, ancient history, music, and cooking fill the shelves alongside sets of china.

After a few moments, ROBERT enters wearing his composer’s uniform. He sits at the table and tries to work on his new opera but is repeatedly interrupted by his past achievements. His uniform—comfortable, loose-fitting everyday clothes—also seems to distract him. He tries making several adjustments to it before turning to face downstage and speaking. There’s no one else in the room.

“Every job I’ve ever had has a dress code, a kind of ‘what’s expected of you as to what you’re like where you work’,” he says thoughtfully. “It’s a big deal, and you conform to that.”

He pauses and looks at a painting on the wall. “Yankee Vermeer”, by George Deem, uses a familiar Johannes Vermeer scene but inserts a baseball player dressed in a full New York Yankees uniform as the subject. He turns to look again at his computer. Later, he won’t remember writing the text he is currently working on.

“It’s very hard, when you’re by yourself, to switch into the idea that you’re working on something,” he says. “I’m sitting here, and I have to talk myself into the idea that I have to work, whereas if you go someplace and put on a uniform, then you’re obligated to do something.”

He pauses again, then adds, “I’ve always envied people who have jobs where they wear uniforms. But you can’t just do it to yourself every day. You have to be a New York Yankee or something.”

Ashley is at work on his newest opera, titled Quicksand. When it is performed in 2014, he will be the only vocalist on stage, although there will be dancers, and other voices will be heard alongside his. It may prove to be Ashley’s most surprising work to date—if only because it is, in certain respects, so conventional. Unlike his previous works, this one is a single story, a linear narrative, and, in fact, it’s a spy thriller.

Quicksand tells the story of a mid-level government operative caught up in a plot to overthrow a dictator in an unnamed Southeast Asian country. The mission goes awry, and the agent is stranded in a hotel room until it’s safe for him to return home. He is on his last mission before retiring and, not coincidentally, is also a composer of operas.

“I’ve never done that before, not that literally,” he says. “Obviously, it’s not me, but obviously, it’s me, too. I haven’t done these things, and obviously, maybe, I’d like to. Everybody wants to be the character in the opera. Nobody wants to go shopping.”

The storylines in Ashley’s librettos are generally drawn from his own experiences. Quicksand flips the formula. The story is fiction but the main character is, in large part, himself. The story has its roots in two distinct interests of Ashley’s: the landscape he saw on a recent trip through Southeast Asia with his wife Mimi Johnson, and a longtime love for mystery novels.

“I started with John le Carré in the 1960s and then Mimi was reading a lot of mysteries,” he says. “She was reading P. D. James and Sara Paretsky, so I read all of her books, but I wasn’t really paying attention until the early 1980s, when I read a particular P. D. James, and it just opened the door. They’re good at writing. You couldn’t ask for better. It’s very good writing about people, and the authors are extremely observant about characters, about people.”

Ashley began looking for a suitable novel to rework into an opera but found that to be more difficult than he’d originally expected. Spy stories tend to have lots of scenes and lots of characters—too much to portray in his usual minimal settings. He decided instead to write his own novel and then adapt it for the stage.

“I didn’t think I could write one until I got back from this tour of Southeast Asia,” he says. “I came back with these images in my mind, but I don’t know where they came from. I just thought, I should write a libretto of linear time and consequences rather than what I’ve been doing my whole life. I must say, I don’t remember doing it. I literally can’t remember sitting in that room and writing it.”

The writing went quickly, but setting it to music proved to be a bigger job, especially when he started getting calls to produce older works of his again. “This all started two years ago, and then I got interrupted by all this good fortune of composers wanting to do my work,” he says.

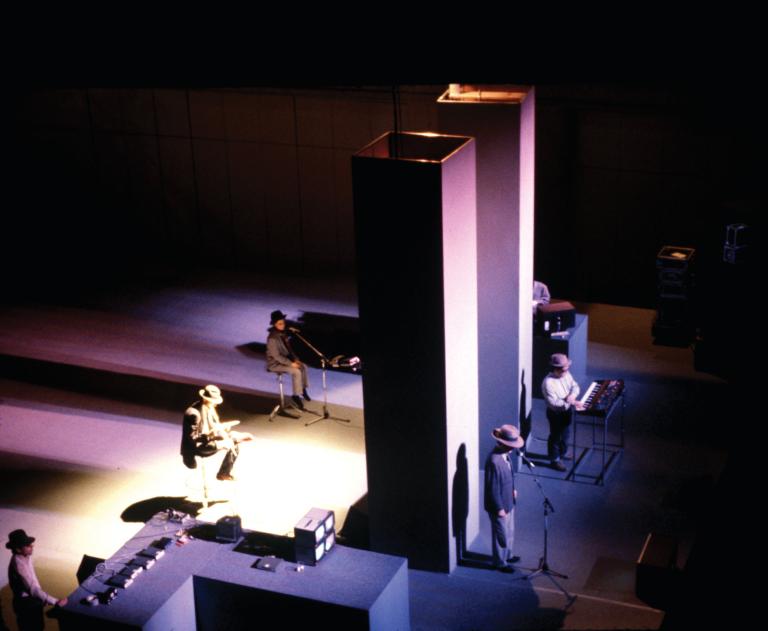

In May 2011, Ashley invited the composer Fast Forward to direct a new production of his 1967 opera That Morning Thing for the Performa 11: New Visual Art Performance Biennial in the Fall. It would be the first time it had been staged since 1969.

“The unusual thing about it was that Bob doesn’t usually get other people to direct his work,” Fast Forward told me. “I think Bob’s come to an age where he’s very excited about doing his work, but he also wants to take some of the strain off himself.”

Ashley and Fast Forward worked together on the script up to the point of beginning rehearsals, at which stage Fast Forward took the production over. The script itself is an unusually disjointed presentation and includes two of Ashley’s best-known pieces—“Purposeful Lady Slow Afternoon” and “She Was a Visitor”. The three scenes last about an hour in total and have no overt relation to one another, but together are devastating listening, dealing with rape and, perhaps, a suicide.

Writing about the initial Once Group production in the Michigan Daily in 1968, Andrew Lugg remarked that the troupe was “all it is cracked up to be” and that the piece “scratched at your soul”, adding, “I feel much better now that it is all over. As I see it (and this, no doubt, is only one of many possible interpretations), this event is about a woman’s suicide, about getting up in the morning and facing it again, about going through another day.”

Within a few years of that original production, Fast Forward—still at home in England—was discovering Ashley’s uncompromising work.

“In experimental music, we looked toward the United States—the Sonic Arts Ensemble, Philip Glass, LaMonte Young,” Fast Forward recalls, punctuating his reflections with laughter. “I was at art college working with sound, and I sort of migrated toward the American composers. I don’t know why—maybe because Americans are so good at marketing themselves.”

Fast Forward soon moved to California to study with Ashley at Mills College and has lived in the US ever since, although the Performa staging at The Kitchen in the Chelsea section of Manhattan was their first time working together on a public piece.

“It went very, very smoothly,” Fast Forward says. “I think that’s because it was a done piece. It wasn’t a commission where it was creating a piece out of nothing. He knew the piece; he knew what the elements of the piece were.”

A month after the Performa production, in December 2011, the cellist/composer/musicologist Alex Waterman and Issue Project Room presented Perfect Lives—perhaps Ashley’s best-known opera—at the Irondale Center in Brooklyn. In a dramatic break from past productions, however, this time the piece was done in Spanish.

Waterman had been working on a book collecting Ashley’s scores, interviews, and other archival materials, and in the process applied to Issue to produce a staged reading of Perfect Lives, which was originally composed during 1979 and 1980 as a series of works for television.

In his excellent biography Robert Ashley (University of Illinois Press, 2012), Kyle Gann considers Perfect Lives to mark the beginning of the composer’s “mature conception of opera”, specifically regarding the innovations in musical structuring. This work, along with Atalanta and Now Eleanor’s Idea, would comprise a “kind of history of American consciousness”, using as foundations (in Ashley’s often cryptic fashion) the fields of architecture, agriculture, and genealogy.

Unlike That Morning Thing, Perfect Lives has a fairly clear setting, if not exactly a linear narrative. The cast of characters includes a pianist, a singer, and a football player, all down on their luck and planning a bank robbery. The piece is structured in seven twenty-four-minute segments to work like a TV series and has been done on video as well as in live performance. Also, unlike Morning Thing, Perfect Lives has seen performances since its premiere and is perhaps Ashley’s most celebrated work.

Waterman got the Issue Project Room commission, but by that point he had lost enthusiasm for the project. “I was totally disinterested,” he says. “I thought that idea sucked. And Bob said, ‘I don’t think you should try to sell people a used car. I think you should build a new one.’” Instead, Ashley and Waterman devised a radically new idea. Using a translation handed out to audiences for a 1992 production in Spain, they created a new version of the opera in Spanish.

Like Fast Forward, Waterman discovered Ashley’s music when he was in college. But in Waterman’s case, the appeal wasn’t immediate. “I really couldn’t understand what it was about,” he says. “It definitely was not love at first sight, but I get obsessed with things I don’t like. Bob’s music sounds kind of like a beer commercial that goes on for half an hour, with this radio voice going over it. It’s a soundworld that’s familiar, and I couldn’t stop listening.”

Then, all of a sudden, “It clicked,” he says, and in 1994 he organized an Ashley festival in The Hague. Now, he’s touring Vidas Perfectas, with two London performances already completed, and presentations scheduled in El Paso and Marfa for 2013, and Brighton in the UK for 2014.

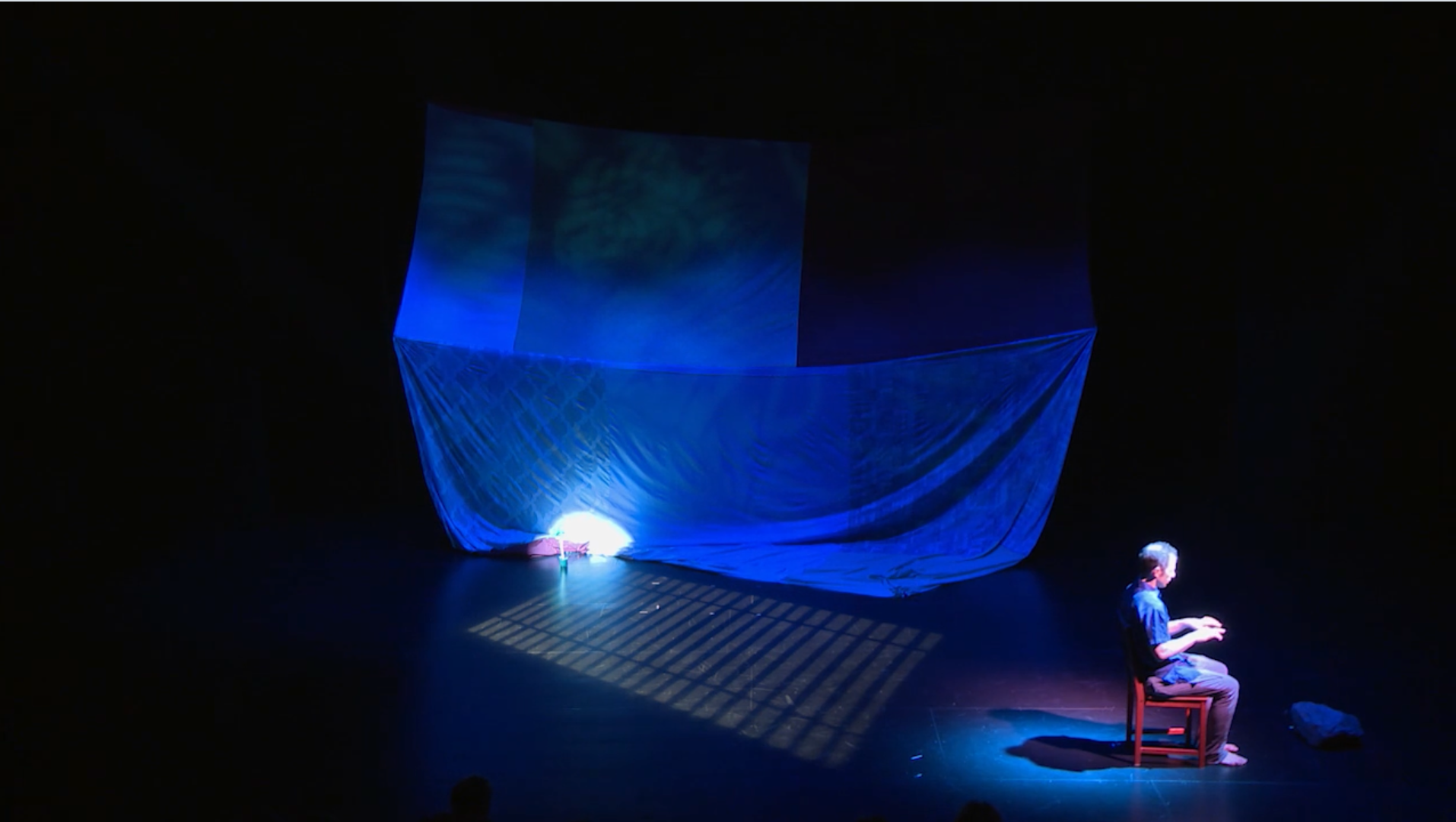

Perhaps the most inventive of these recent revivals was a reimagining of Ashley’s Automatic Writing, conceived and performed by the collective Object Collection in conjunction with the Incubator Arts Project in November 2011.

Unlike the other Ashley pieces that were given new life in New York City at the end of 2011, the composition Automatic Writing wasn’t conceived for the stage. The sound piece is built around the involuntary utterances Ashley sometimes makes (although he has never been diagnosed, Ashley believes he has a mild case of Tourette’s syndrome).

The recording—released in 1979 on Lovely Music, Ltd, the label founded by Mimi Johnson—features overlaid tracks of Ashley’s voice paired with a synthesizer bassline and Johnson speaking in French. It’s a dramatic forty-five-minute artifact constructed over a period of five years.

In Object Collection’s hands, and under the guidance of director Kara Feely and composer Travis Just, Automatic Writing became an ensemble piece presented live on stage with multiple video monitors displaying the members of the ensemble, repeated as if in a claustrophobic hallucination.

“I talked to Ashley a lot about how, in relation to his operas, there are sort of characters in it—the voice, Mimi’s French voice, the disco music,” Feely says. “In a way, I’ve always thought of it as very theatrical. There’s no story—there’s nothing really happening. It’s very thick, and it never really settles into one thing.”

Feely and Just have collaborated on a number of unconventional operas—intense productions with loud electric guitar and fractured storylines. There’s a clear lineage stretching back to Ashley’s work, even if it’s of a decidedly different generation.

“I like the idea of it being the kind of thing you’re not supposed to do,” Just says. “Automatic Writing is this studio thing, this monolith, and I thought, ‘What would it be like to deal with it as a living thing?’”

Just comes from a background of both improvisation and classical composition, having studied with Andrew Cyrille, Wadada Leo Smith, and James Tenney. Discovering Ashley’s music, he says, changed the way he approached his own work. “I can’t imagine coming across him and going, ‘Well, it’s back to writing sonatas.’ It would be historically inconceivable.”

All of this activity was a much-deserved tribute to an eighty-three-year-old composer who arguably cleared the path for such new music luminaries as Laurie Anderson, Philip Glass, Meredith Monk, and Steve Reich. But at the same time, Ashley says he never expected to see other people performing his work.

“I was never interested in writing music for somebody else to play without me,” he says. “My activities in doing that were so unfortunate. You give a score to an ensemble, and they go, ‘Oh, you can’t do this, you can’t do that.’

"I think the deepest part of you that wants to make music wants to make it yourself. The part of you that thinks, ‘I want to make some music,’ you think, ‘I want to make some music.’ But I’ve had really wonderful experiences in the past year with young musicians I admire very much who want to do pieces of mine.”

Perhaps something should be said here regarding the word “opera”. It’s a troubling term: one that goes in and out of vogue, but, in general, probably dissuades new fans more often than it wins them over. Ashley ushered in a new operatic sensibility in the 1970s, although perhaps the primary reason the work was classified as a new vogue in opera was that Ashley himself used the word.

In the last few years, New York City has seen a resurgence of the form (or at least the term). The imaginative works of Object Collection are only one example. Jason Cady’s 2013 album Happiness is the Problem is a boisterous, sometimes hilarious, two-act work about young, struggling roommates in Brooklyn who discover a compound that triggers happiness.

Cady is a member of Experiments in Opera, an artist-led, nonprofit opera company he co-founded with composers Aaron Siegel and Matthew Welch, which has staged works at (Le) Poisson Rouge and Roulette. The group collaborated with the new music ensemble Hotel Elefant in February 2013 on a night of ten-minute operas at Issue Project Room, during which an excerpt of Ashley’s Quicksand was presented.

The solo piano piece “Resonant Combinations” had no libretto or singer. If it counts as an opera, it is perhaps the most radical redefining of the term Ashley has perpetrated to date. What the piece did do, in any event, was to introduce some of the harmonic structures he had been working with.

“When Aaron Siegal asked me to make something, I happened to be working on the succession of harmonies in Quicksand,” Ashley explains. “There are sixteen chords. I had figured out a way to do it all at the piano. As in so much of what I’ve done, there’s a sort of focus pitch for each scene; so if there are sixteen focus pitches, there are sixteen scenes.

“In the singing, the focus pitch belongs to one of the singers, but I hadn’t really gotten around to that. It’s like a harmonic template for Quicksand. What happens in that piano technique is you depress the notes of the chord silently and then play the focus pitch. Since the dampers are depressed, it creates a sort of harmonic halo around the focus pitch.”

This provides a small glimpse into the way Ashley’s music works. His compositions aren’t conventionally scored and the music generally follows the flow of the text, which has been likened to the cadence of Ashley’s own Michigan accent. As in traditional opera, the music is there to support the vocals, but in the case of Ashley’s operas, the voices are closer to speaking than singing. (Gann’s book includes an excellent analysis of the different mechanisms used in each of Ashley’s major works.)

The music can be challenging to listen to, in that it’s almost easy listening. It defies the listener to pay attention. It’s repetitive, easy to ignore, like—as Waterman says—a beer commercial that goes on for half an hour. It’s monolithic and, at the same time, regularly uses electronically produced or altered sounds that could lead a listener to justifiably ask, “Are you serious?”

Ashley’s 1998 work Your Money My Life Goodbye, for instance, is loosely based on true stories about a financier with Mafia connections who stole $130 from the Vatican, and a Russian spy who seduced a NATO secretary and obtained confidential information. The hour-long opera is filled with synth sounds that wouldn’t be entirely out of place in the Starland Vocal Band’s proto-disco hit “Afternoon Delight”.

Most of Ashley’s operas also include a more overtly musical passage, something he refers to as his “pop songs”. They’re pretty well removed from anything on the Billboard charts, but they also stand out against the rest of his works.

“In the recent operas, from Perfect Lives onwards, I always put in a song that’s somewhat in a popular music format,” he says. “It’s got a symmetrical beat, and it’s got the kind of singing that goes with a synchronized beat. I put these in as sort of time markers that go with each piece, anchoring the opera in a certain period of time.

“I felt I had to do it, but I didn’t really understand it until I’d done eight or ten of them. It represents a certain moment in the American history of things, so you have a song that sounds like a country song of a certain era. It’s about when I composed it. I hate to say it, because it’s too grand, but it’s like Hitchcock putting himself in all his pictures. But I didn’t start with that intention. I always felt obligated.”

Even more radical than his music, however, are the innovations Ashley has developed in narrative approach. His operas consist of stories, but the stories are told, not acted out. Generally, they are told not from a single omniscient voice but by four all-knowing narrators with unclear relationships to each other. While there have certainly been many stories told by multiple narrators (Faulkner and the Old Testament come to mind), those typically share a focal point; in Ashley’s operas, the narrators and their stories bear no clear relationship to one another.

“I couldn’t imagine any way that a third-person narrator could string all those stories together,” he says. “You can play with who comes first and what you know from the first story that can help explain the second story. Obviously, I’m happy with it. I could do it with two or eight people. I just happen to have four people who I like very much, whose singing I like very much. It’s easier for me to think about telling a story because I have four voices telling the story.

“In the librettos that I wrote before, there’s no concern for linear time,” he adds. “My librettos are all about scenes that are assembled into the final opera, but the scenes all start with somebody telling a story about somebody else. Except for my idea of how they go together and why there’s no linear order to them, that’s my conception of a libretto, and I think it’s in the tradition of modern literature more than it is in modern music.”

All of which only helps so much in explaining the opera Ashey is currently working on. In Quicksand, Ashley will be the only singer on stage, but his usual company—the composer's son Sam Ashley, along with Thomas Buckner, Jacqueline Humbert, and Joan La Barbara—will be heard in a prerecorded tape, improvising approximations of the melody line to create a harmonic cloud around Ashley’s voice. The staging will be completed by other longtime Ashley associates: Tom Hamilton will do sound design; David Moodey will handle lighting; and Steve Paxton will choreograph the piece.

How clearly the espionage and the harmonic clouds all come through on the stage, of course, remains to be seen. Needless to say, Ashley’s works can be puzzling—something the composer doesn’t deny.

“I would never expect the audience to understand those technical areas the first time because it’s just too complicated,” Ashley says. “You don’t understand novels the first time you read them. You have to go back to see how they work. When you go to see La traviata, most of the people in the audience already know the story and already know the characters.

“What I owe the audience on the first listen is the sound of the voice and how that voice fits with the orchestra, and how the voice and orchestra fit into the space so that the audience can enjoy something without knowing much about it—the same way you might enjoy an Indonesian meal without knowing how it was made. I think all you can ask for is that it be enjoyable the first time, and then you can come to understand it better.”