What would you do if I told you that under this box

lies the names of the members of the Residents, the most elusive, mysterious band in rock history. Would you want to know? Would it make a difference to you? Would you expect to recognize the names? Go ahead, get a quarter and scratch it. What happened? Did you tear the page of your fancy art journal? Oops, soz.

OK, what if I told you that under this smaller box

lies the answer as to whether or not it matters who the Residents are. Would you believe me? Do you think the answer is there?

Yes, it matters who the Residents are.

No, it does not matter who the Residents are.

Have you grown to distrust me yet?

I’m not sure I can proceed here if you aren’t putting any faith in what I say.

Or even if you are.

Celebrity Secrets Revealed

What if I told you that I have met the Residents and I was not even sworn to secrecy about their identities? And what if I said there is sort of an unspoken understanding that there’s no reason to ruin the fun, a sort of unspoken honor system, like the way all the rock mags had photos of KISS without their makeup in the ‘70s but nobody printed them because they didn’t want to spoil the party. What if I told you that I am going to reveal the truth because someday it will come out, and if I seize it now, I will be something of a star, infamous at least, a pariah perhaps, but a well-known one in the annals of music journalism?

Would you think I was being an asshole?

What if I asked you this: Which is more important, to discuss who the Residents are or to discuss their work? The work of a group of artists who made their way from swampy Louisiana into the San Franciscan Summer of Love and within a few years time were donning masks, making films, and emblazoning a local record store with swastikas. Are their names, away from the work, any more important than the names of Banksy, Cost, and Revs, or Alan Smithee?

OK, I’m sorry about the thing with the boxes above. It was gimmicky, I know. But here we go. In the parlance of the day, I should first say:

SPOILER ALERT

Here goes.

There is only one original member of the band remaining in the current lineup. That should not come as a surprise to people who have followed the group. After all, that singing voice has been pretty consistent throughout the band’s 40-year recording history, if deepening with age. And as it happens it is a name people know and once you know it, it just seems obvious. I guess I shouldn’t say it except that I don’t see how it matters. It won’t inhibit the work he does as a painter or a musician, so I’ll just put it in print. While other musicians have come and gone, sculptor, filmmaker, and installation artist Paul McCarthy has been the only consistent member of the Residents.

Here’s how I know this. I do a weekly show at the radio station WFMU. One of my fellow co-hosts there is a monologist who goes by the name “Hearty White”. He, too, was a member of the band at one time and he told me over drinks one night all about his involvement. He played guitar, banjo, and piano on some of their early albums and contributed to the songwriting, though he was careful to tell me that he was never the primary creative force. He didn’t tell me I could repeat what he said, but he didn’t tell me I couldn’t. We were both pretty drunk.

I don’t know if the similarity to the name “Paul McCartney” had anything to do with their building a mythos early in their career that they either hated or, alternately, actually were the Beatles, but I expect so. From there, things fall together pretty easily. Mike Kelley and his Destroy All Monsters bandmates have been involved with the band, as have Fred Frith and Chris Cutler (of Henry Cow and the Art Bears), Andy Partridge (of XTC), Neil Sedaka, Nina Hagen, Adrian Belew, and, of course, Snakefinger. We’ll get back to Snakefinger. Paul McCartney, too.

Anyway, there you go. Now – does it matter?

The biggest question in the Residents mythology is not one of identity but one of philosophy. But with such a big red herring of a white elephant in the room as their much-guarded identity clouding the issue like a forest through which we can’t see the trees any easier than the nose on our societal face, it’s impossible to discuss them as a band (the collective singular) without discussing them (as individuals) and who they are. And discussing them as individuals is every bit as impossible to do as it is possible.

Portions Of This Essay May Be Fabricated.

Here is the real way I learned the identities of the Residents: A press representative at the Museum of Modern Art said he would arrange an interview with them for me and introduced me to them, not knowing that they weren’t doing interviews.

Here is the real way I learned the identities of the Residents: The Singing Resident, sometimes also known as “Mr. Skull” or “Randy” (but never “Randy Skull”) incorporated me into a solo concert he did called “Sam’s Enchanted Evening” at the Abron’s Arts Center in Manhattan and afterward I was invited backstage.

Here is the real way I know the identities of the Residents: I am – or have been – a member of the band.

That is probably patently untrue, that last one. But ultimately, who the Residents are, or were, or might be, doesn’t matter. The Residents are the image they have sold and continue to sell on over 60 or so albums (and a considerable number more of live albums, compilations, and reworkings), exploring aspects of depravity, depression, and sexual frustration.

The Residents are four guys who just wanted to be pop stars without taking credit for it. The Residents have also fairly certainly been more than four guys, and a couple of women besides. The Residents are currently three guys, although some say only two and some have said that really it’s one.

The Residents are also or may be anyone who wants to be them, or one of them. As they wrote in the liner notes to their 2002 album Demons Dance Alone, “If no one claims to be a RESIDENT, doesn’t that mean everyone is a potential RESIDENT? Don’t we all get their mail? ... THE RESIDENTS continue to flourish, joining Jesus, Vincent Van Gogh, and Betty Page as virtual characters thriving in the residue of life.”

There you go. Now – does it matter?

And if it doesn’t, what does?

Who (Else) Are the Residents?

With as much concern as is given to the subject of the Residents’ identity, the question often overlooked is, “Who else are they?” Or, perhaps better put, “Who aren’t they?” Maybe there’s something to be discerned about who they are by looking at who they aren’t.

Over the course of their long and strange career, the Residents have occasionally dropped their façade only to don another one. Mark of the Mole, the 1981 release of the first part of their epic opera The Mole Trilogy, was followed by two imaginings of music from the world of the Moles and their nemesis race, the Chubs. About 25 years later, they became another band, the Ughs, a purported free jazz group conceived as a process for creating the music for The Voice of Midnight, the most straightforward piece of storytelling they’ve ever put on record.

Mark of the Mole was the band’s most ambitious undertaking to date. Not just their biggest story – a struggle between the Moles, forced out of their underground homes by flooding, and the more sophisticated Chubs, who exploit them for as long as it serves them – it was also the grist for their first international tour. The project was originally conceived as a series of six albums – three telling the story of the vying races across generations and three providing documentation of their music – although only three were completed: Mark of the Mole (telling part one of the story) and two fictional ethnomusicologies: Tunes of Two Cities and The Big Bubble.

Tunes of Two Cities (1982) reflects the Mole and the Chub societies through their music and as such is a hilarious re-imagining of work songs versus cocktail jazz. It opens with the vapidly catchy “Serenade for Missy”, which could nearly be a Henry Mancini tune were it not for the rubbery keyboard sound. (The band employed the new E-Mu sampling synthesizer for the sessions). The album progresses from there, alternating between Chub light jazz and rhythmic Mole chants.

It wasn’t the first time the Residents had imagined tribal music. The 1979 album Eskimo (oddly enough the band’s popular breakthrough) was a soundscape of blowing wind and chants derived from television commercials. But that album was the Residents overtly imagining Inuit life. The Mole’s music is a bit reminiscent of Eskimo, and in fact shades of Chub music might be heard in Diskimo, the follow-up EP of Eskimo dance remixes. But it is them creating – not aping – a culture.

In 1985, the band released its second volume of music imagined for the world of Chubs and Moles, this time complete with band name and backstory. The Big Bubble was a pop band that sang in the forbidden Mole language and the members of which were all Crosses, products of the inevitable cross-breeding between the warring factions. Actors were hired to portray the Big Bubble on the album cover (the Residents have denied rumors that it is them in the photo). The cover was then designed to look as if the Big Bubble cover art had been pasted onto a Residents album, adding (almost literally) another layer to the guise. The original release even looked to have a fake record label on top of the real one.

The album The Big Bubble is an interesting take on pop music (and the band has always been very concerned with pop music). It still sounds like the Residents but is cleaner and simpler. From a strictly aesthetic stance, its interest lies more in being a Mole artifact than in the music. It’s a fun listen but doesn’t stand up to their work of the time – nor was it really intended to. It is the Residents posing as others while having others pose as themselves.

Twenty-four years passed before their third band-within-a-band (or band-outside-a-band) emerged. The Ughs was conceived as a way to give themselves a new framework to conceive the music for The Voice of Midnight, their setting of an H.P. Lovecraft horror story. The liner notes refer to what they came up with as “ritualized, primitive free jazz” but the relation to jazz is a mystery (unless they meant simply that it was freely improvised).

In any event, rarely have the Residents sounded so little like the Residents. If it’s reminiscent of anything in their catalogue it’s the music they did in the ’90s for the Discovery Channel series Hunters: The World of Predators and Prey. Synthesized strings, cricket chirps, and pan pipes envelop the album with familiarly simple, inverting melodies, marches, and chants seeping in. “The Lonely Lotus” even bears a strong resemblance to the Moles’ “Won’t You Keep Us Working”, augmented by digital strings and programmed beats. What there isn’t is vocals – or at least lyrics. This isn’t even incidental music; it’s sketches for incidental music. But the outcome is still effective. As always with the Residents, by whatever name, the music is evocative, even if we can’t quite tell what it is that’s being evoked.

Meet The Residents

Perhaps it’s best to start in the middle, or somewhere near the one-quarter mark, with a pair of antithetical albums and a mentor who may not exist. We’ll say he does, however, at least for the moment. The Residents have always been about creating a mythology, putting information forward through liner notes and their management mouthpieces in the Cryptic Corporation. For purposes of this essay, we will consider the information coming from Cryptic to be the primary source, even if it might be questioned.

But before we start, a little groundwork.

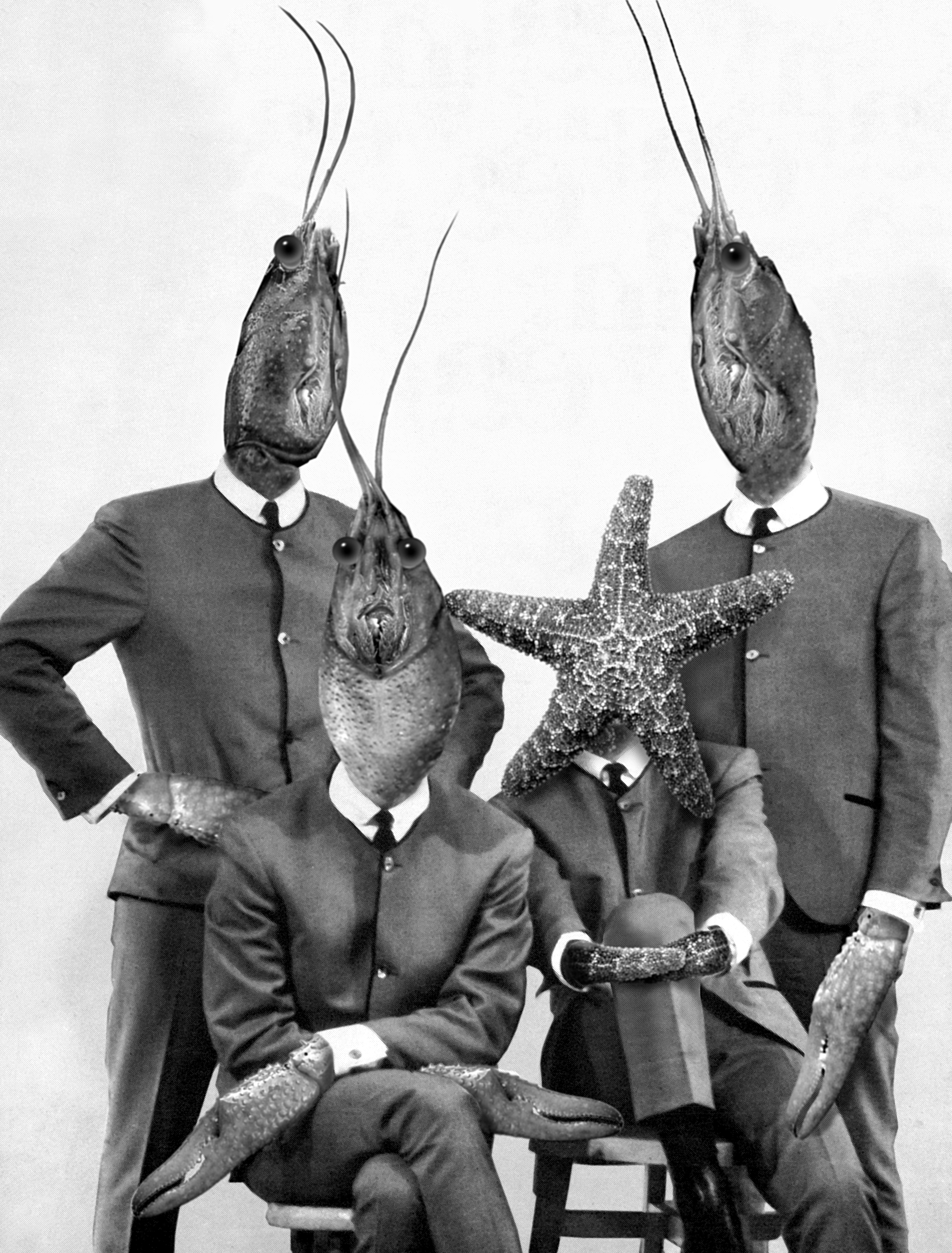

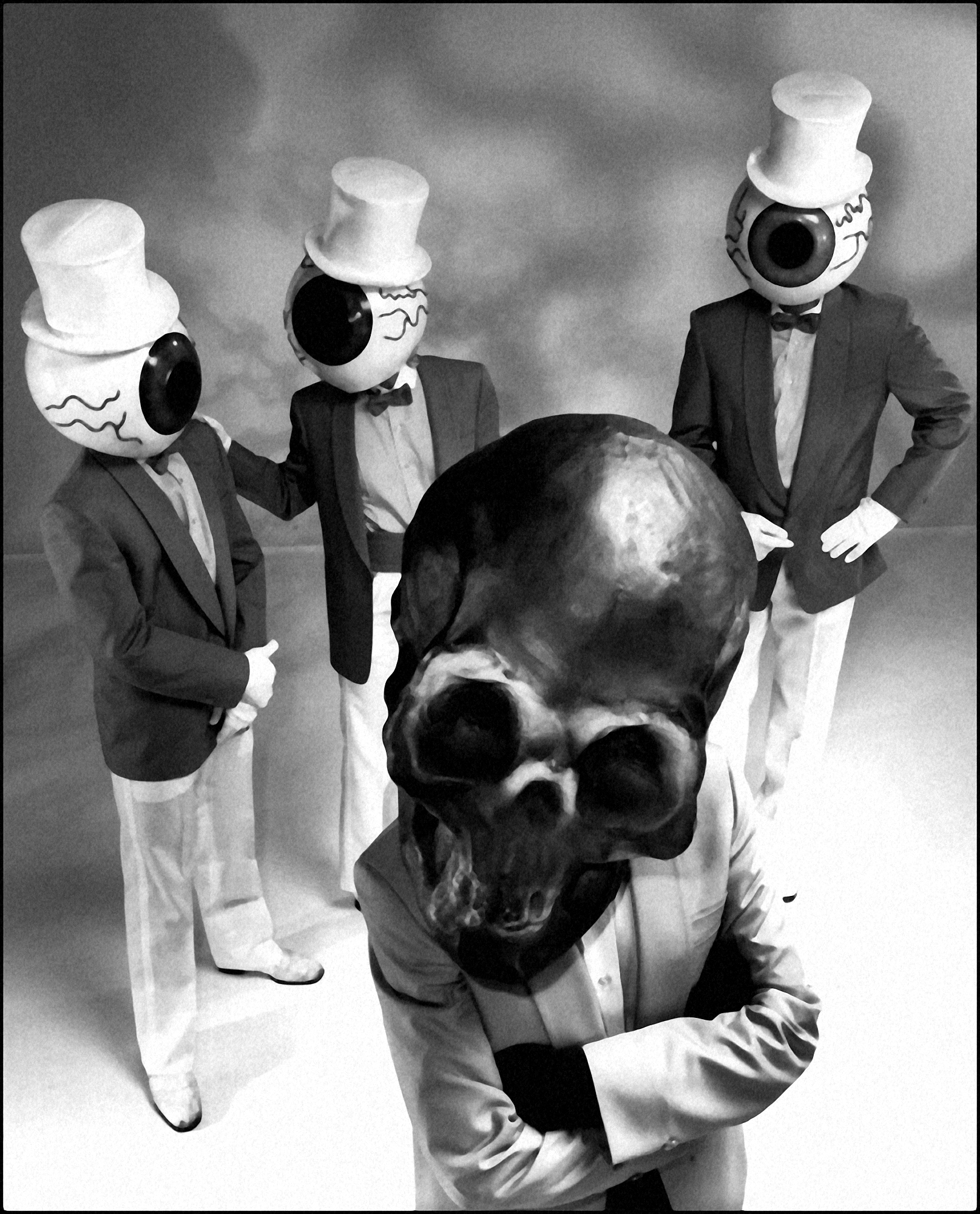

Beginning with their 1974 debut Meet the Residents (the original art lifted from Meet the Beatles with grotesque caricatures filling in the Fab Four’s half-shadowed faces), the band members' identities have been a closely guarded secret. Interviews are conducted by representatives of the Cryptic Corporation, leaving the band members free to create their unusual, mutant pop. As with any secret identity — the Unknown Comic, the band KISS, Charlie Townsend (who employed “angel” detectives on television) — it’s a good way to create buzz.

The Residents obviously couldn’t claim to be the Beatles (a rumor they alternately encouraged and denied in their early days) had they shown their faces. But by not showing their faces, they could be whatever they wanted. It’s a simple but powerful device. KISS is a mediocre band at best but became a phenomenon by projecting a constructed image and keeping their real identities hidden. Diamanda Galas is a diminutive woman with a sharp sense of humor who, made up like a ghoul in drag, becomes a demonic diva. The Art Ensemble of Chicago played the role of “urban bushmen” to the delight of Paris in the late ’60s, using costumes and face paint to create a dichotomy of primitive sophistication.

Of course, masks were part of performance long before there was such a thing as a recording industry, from Japanese Noh theater dating back to the 14th century to Europe in the Middle Ages, where masks were integral to feasts and festivals until prohibited by the church. The word mask comes from the Old Italic masca, which refers to an evil or hideous character, and in fact, masks more often than not connote something antagonistic. They have been especially popular in heavy metal, with such bands as Gwar and Slipknot creating cartoonish, gruesome identities. But in the Residents’ case, the masks (most famously their oversized eyeball heads) have served as blank slates. The fact that they have no faces, no identities allows them to tell their melodramatic tales of loneliness and disfigurement – of circus freaks and murderers – either as impartial observers or as the villainous protagonists themselves. Their tales can be horrific, and they can be hilarious, but we are the ones who feel the pain or get the joke; the tellers are either neutral or sympathetic in a way they might not be with human faces. However much they thought it through at the beginning, the masks have served them well.

Little is really known about the band, although theories abound. What we do know (or what the Cryptic Corporation has told us) is that the band was created by four men who moved from Shreveport, Louisiana, to San Francisco in the late ’60s to pursue filmmaking, but found it easier to realize soundtrack music than to realize their obtuse screenplays. A rejected demo sent to Warner Brothers was returned to “residents”, giving the band its name. Following the rejection, The newly-christened “Residents” set up their own label, Ralph Records, and distribution channels, a rarity in pop at the time. The Warner Bros. demo set the four young men on one of the most unusual careers in rock. Since then, they have used Inuit song, Elvis Presley, the Old Testament, and Prussian novelist E.T.A. Hoffman as source material, creating an unparalleled body of work in the pop world.

And they are a pop band. With heavy keyboards, electronic percussion, and slurred vocals, it’s arguable that their music isn’t rock. But the notion, the image, of a pop band (a musical group traded on the pop-culture commodities market) is central to their decades-long project. Despite the fact that there are rarely only four people on stage at their concerts and that the body types have changed markedly over the years, the presentation of four men (ie. John, Paul, George, and Ringo; Gene, Paul, Ace, and Peter; Bingo, Bango, Bongo, and Irving) is key to their carefully constructed image. Ultimately, the only way to deal with the Residents is to accept their mythology. Getting hung up on the question of identity only gets in the way of the music.

On With The Myth

Legend has it that sometime in the early 1970s, an avant-garde artist from Germany named N. Senada and a British guitarist Philip Lithman were traveling together through California when they met the members of the Residents. Lithman – later rechristened “Snakefinger” by the Residents due to his instrumental prowess – would be a frequent collaborator with the band and release albums of his own on their Ralph Records. N. Senada is a cloudier figure. Some have speculated that he was Don van Vliet who lived and worked on Ensenada Drive in San Francisco with his group Captain Beefheart and the Magic Band. The members of the Residents may have visited and been inspired by Van Vliet and his off-kilter blues, the theory goes. Others have suggested that Senada might have really been the composer and instrument builder Harry Partch, who also passed through San Francisco during the early 1970s. But here we take the Cryptic Corporation at its word: N. Senada was a little-known composer, theorist, and conceptual artist who introduced the Residents to his “theory of obscurity”, a guiding principle in the band’s career.

The theory of obscurity holds that a kind of artistic purity can be reached by making a work that will never be seen or heard. So, having recorded one album that Warner Brothers rejected (heavily bootlegged and much later remixed and released by the band) and self-releasing a second album (Meet the Residents), the band in 1974 set about making an album that no one would hear. Four years later, having fled the country under the fire of an album deadline they couldn’t meet, the Cryptic Corporation dug out the album and released it as Not Available. The band was OK with that, at least according to the myth. Since it had been created with the intent that it never be heard, the work was pure – even if it eventually was made public.

The End Of Obscurity

The theory of obscurity flies in the face of rock dogma, of the logic of commercialism, and of the Residents’ own early use of the Beatles as an iconic mirror. Art, at least in America, exists in the marketplace. It is essentially the same thing as entertainment; if it’s good, it will sell. N. Senada taught the Residents that for their art to be of high quality, it shouldn’t sell. It shouldn’t be available to be bought or sold. To the work of the Residents, who generate a remarkable amount of merchandise, “unavailable” might not be the aptest of descriptors.

As perhaps happens with many mentor relationships, the Residents’ struggle with Senada’s philosophy as central to their work. Their identities may be hidden, but mass appeal — commercial success — has always been a key component to the Residents project, whether or not pursuing it has. Theory of obscurity aside, their Beatle-assimilation and their regular rotation in the early days of MTV suggest a focused interest in the market. Whether they wanted it, whether they expected it, marketplace success has been a large part of their package.

In 1980, the band released its seventh record, The Residents’ Commercial Album, which can be seen as the centerpiece of their take on pop stardom – and the antithesis of the theory of obscurity. The Commercial Album is both an indictment and a plea. The album’s name clearly, if mockingly, suggests the appeal of market success, as does the cover, featuring pictures of Barbara Streisand and John Travolta with the Residents’ ubiquitous eyeball masks overlapping the stars’ eyes. The album contains 40 songs of precisely one minute each — complete songs, they (or their management) argued at the time, since the average three-minute song could be boiled down to 60 seconds. It was also at that time the average length of a television commercial, suggesting that pop songs and product jingles were not so different. In 1999, Moby sold licensing rights to every song on his album Play, making commercialism cool. His act of capitalist bravado was also, it’s true, greeted with cynical criticism, but 15 years later, how often are recorded artists accused of “selling out”. Today it’s just a matter of survival. But in 1980, on the part of our masked heroes, suggesting that every song on an album could be a commercial of sorts was both a covert criticism of the market economy and an overt (if ironic) bid for attention.

The Commercial Album was sandwiched between two of the most ambitious projects the band has ever taken on: 1979’s Eskimo and 1981’s Mark of the Mole. (A five-song EP titled Babyfingers also fell between Eskimo and Commercial.) Their appeal for mass popularity, more explicitly stated, came between a record of fake Inuit songs and an opera about a war against a tyrannical regime in an underground land of varmints. Eskimo was hardly a commercial venture, and not surprisingly, was inspired by Senada. Nevertheless, it sold more copies in the first five weeks than every other Residents record combined to date, eventually moving more than 100,000 units and actually denting the top 40 in Greece. Interestingly, the band used commercial slogans to create their “Eskimo” language: careful listeners will pick up such phrases as “Coca-Cola adds life” and “You deserve a break today”, setting the stage for the pop jingles they would pursue next.

Coming on its heels, The Commercial Album was a championing and condemnation of popular music and popular culture. The Residents had received by far the most attention of their career with Eskimo and followed it with a perplexing set of heartbreaking ditties. The album contains 11 songs about love, nine about loss, nine about loneliness, five too obscure (or simple) to categorize, and six instrumentals, each tailored to be exactly 60 seconds, with tape speed altered where necessary to hit the mark. Between an album about Arctic struggle and one about tyrannical governments, the Residents made an album that was 75 percent about love or the lack thereof — no doubt an apt reflection of the concerns of popular music.

The band had long used guest musicians on their albums, saying they were primarily producers who would bring in people to play what they couldn’t. But this was their first record to include well-known figures from the rock world (or at least to credit them on the sleeve): Fred Frith and Chris Cutler of Henry Cow and the Art Bears, Andy Partridge of XTC, and new wave songstress Lene Lovich (the latter two under pseudonyms). Some of the songs would be revisited and rearranged on eight subsequent records.

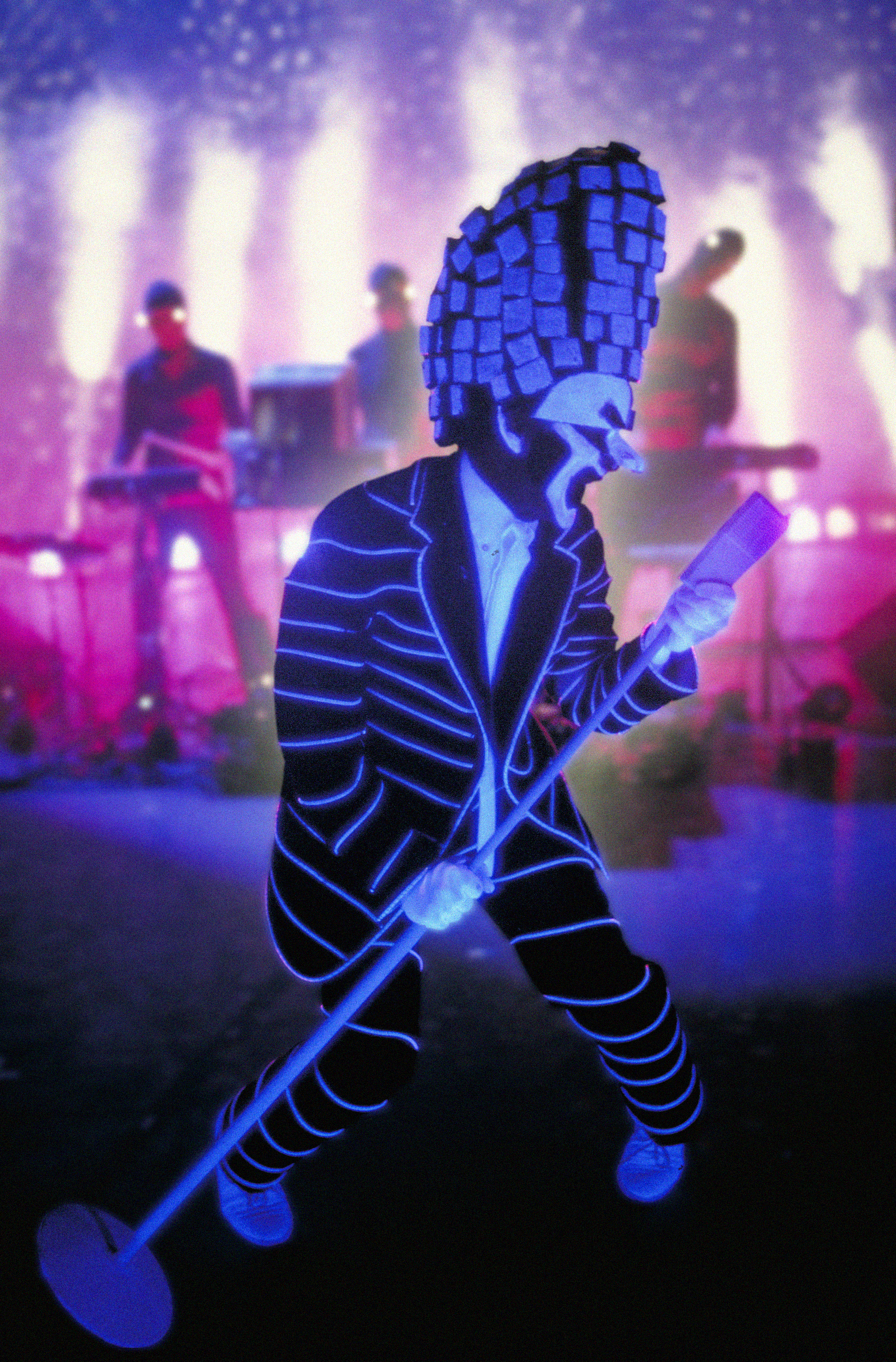

The Commercial Album was the first Residents record of new material to be licensed by Ralph for international distribution, with imprints issued in England, France, Germany, New Zealand, and Australia. UK-based PRE Records even created a “Commercial Single” with six album tracks and two non-LP cuts provided by Ralph. Cryptic cut a deal with the Phonogram and Celluloid labels to fund the production of four “One-Minute Movies”, which ended up in rotation on MTV during its infancy. But the most interesting promotional scheme came from Cryptic itself. Forty one-minute ad spots on San Francisco radio station KFRC-AM were purchased and filled with album tracks; the entire album was played over the course of a day in a move that was criticized in Billboard as payola.

The album sold respectably well, although not to the degree of Eskimo, and garnered decent reviews — which perhaps is in part a sign of its time: Unlike today, when a recording studio, pressing plant, and distribution center can all be housed in a laptop, what the Residents had built by 1980 was rare. Putting out a piece of vinyl with international distribution was in itself enough to get you noticed by Rolling Stone. Through mail order and international distribution, it was readily available.

But whatever commercial viability might have been garnered by The Commercial Album was quickly razed by The Mole Show’s underground rebels and dissenting pop stars, which also saw the band’s first major tour and the end of their first era. Details, as always, are murky, but after the tour two of the four founding members of the Cryptic Corporation left, and – at the same time – the musicianship of the band changed dramatically, perhaps not for the better. You do the math.

The End Of The Century

The members of the Residents have always been interested in keeping up with the times and using new technology. Already pioneers in the music video, the band started using new digital and Midi technology, and programmed beats and processed sounds became a major part of their sound map. In the 1990s, they were quick to jump onto the CD-Rom, releasing interactive albums that took the form of labyrinth exploration games. They released three albums of covers – George & James featuring interpretations of music written by George Gershwin and James Brown and Stars & Hank Forever reworking the music of John Philip Sousa and Hank Williams and The King & Eye, which cast Elvis Presley as a tragic hero with a narrative intertwined with covers of 16 of Presley's hits. But arguably, between 1982 and 1998, they only released one great album: 1988’s much overlooked God in Three Persons, which told the story of a deity in the form of conjoined twins in an hour of iambic pentameter with a multi-tracked Greek chorus. It stands today as one of the band’s strongest efforts and marks the transition from an oddball musical group to one of the most unusual storytelling troupes ever known.

Technology is far too often seen as something used to fill in when musical ideas or abilities are lacking. In the Residents’ case, however, that might not be too far off the mark. Many of the albums released in the 1980s and 1990s seemed sterile – electronic foundations with heavy-metal-styled guitarists (filling in for the departed Snakefinger) riding over the top. But at the same time, the storylines of their projects grew both clearer and more inventive. As the little hand on the millionometer clicked over to 21, the stories started to supersede the songs. Wormwood: Curious Stories From the Bible, released in 1998, featured re-tellings of murder and incest tales from the Old Testament. Demons Dance Alone (2002) was a post 9/11 rumination on loss and death and remains the most overtly emotional album in their catalog. Tweedles (2006) attempts to make a sympathetic character out of a sexual predator. The Voice of Midnight (2007) was a reworking of an old ETA Hoffman horror tale, done with actors (rather than themselves) playing the parts.

Along the while, there were countless other records: live albums, instrumental versions, demos, outtakes, and ancillary storylines. There was also Timmy, a series of short, animated videos about a young, inquisitive boy caught up in strange surroundings, which marked the band’s first venture into using YouTube not as a means of promotion but as a forum for distributing material. Turning YouTube into not just a vehicle for storytelling but a model for it led to what might be their last great work. Through a series of video clips (later released on DVD), an album (and several follow-ups), and a large-scale concert tour, Bunny Boy told the story of a hermit who apparently committed fratricide.

These are the touchstones in a collective career for which no credit was ever quite taken. They made a name for themselves remarkably without revealing their names – at least up until 2010 (39 years after recording the demo rejected by Warner Bros.) and the Talking Light tour. The band had barely finished the Bunny Boy tour before setting off on its most overtly storytelling performance project to date. Talking Light had the smallest lineup of the band yet and began with a phrase which, four years later, has become as commonplace to Residents fans as Johnny Cash’s “Hello, I’m Johnny Cash” but at the time was absolutely shocking: “Hi everybody, it’s me! Randy! Singer for the Residents.” And with that, the whole of the landscape changed. Randy introduced his bandmates – Chuck on keyboards and Bob on guitar, explaining that drummer Carlos had left the band and gone back to Mexico. The names, as became apparent over the following months and with the first projects to be released by individual band members, were pretty clearly fake. Randy’s last name was revealed as “Rose” – if not copped from the late ‘80s metal guitar hero Randy Rhoads then still just too-perfect a rock star name. And Chuck’s last name, Bobuck, suggests the one name you can’t sing in “The Name Game”. And Carlos, well, we hardly knew him.

The End Of Anonymity

Why, at this stage in the game, give yourselves names? It’s hard to say, but doing so has allowed for separate avenues of activity under the Residents banner for the first time in their history. Randy did a few performances of “The Residents Present: Sam’s Enchanted Evening” without the other member(s) of the band in 2011 and 2012. He has also continued with the short video format for his storytelling. The YouTube series Randyland concerns the travails of the lead singer of the Residents, impoverished and unbalanced, living in a single room and frequently visited by aliens. Meanwhile, Chuck has released several albums of instrumental, Residentesque music. But all the solo projects pale compared to the band’s output and beg a surprising question, have the Residents broken up? The Beatles played a concert on the roof of their Apple headquarters to mark their end. They also had names. If you’re in a reasonably successful band for 43 years and never reveal your name, how do you launch a solo career?

And for that matter, how much of a new career do the newly named Randy and Chuck want to launch? Assuming they were 20 in 1970 (if only to make the math easy), that would put them in their 60s today. It’s hard not to wonder how far they could be from hanging up their masks.

But maybe they could take a lesson from that other famously masked band of the ‘70s. In July, KISS announced that it was in talks to launch a TV talent show to find replacements for Gene Simmons and Paul Stanley, the two remaining members of the original lineup. All one need do is apply the grease paint to be sold as a part of rock royalty. Maybe the Residents should do the same. After all, if no one claims to be a resident, doesn’t that make us all potential residents? Don’t we all get their mail?

Kurt Gottschalk interviewing The

Residents, photo by Ariella Stok