I wasn’t aware of Dawang previously. I’d heard of Black Wolf and Yingfan but never connected the dots with these names. When I was in Taipei for a gig in the winter of 2011, I expected to meet some of the guys at Kandala Records, and I did exactly that: Yousheng, Etang, and Dawang.

There was an encounter at a performance before we met. It was on the second floor of the Taipei Contemporary Art Center, an event organized by White Fungus and YAO Chung-Han at Kandala, a shared stage with DINO and Wang Fujui. My solo performance included the usual feedback system: sometimes at a continuous and ear-piercing high frequency. Something unexpected began to happen. Something diffusing and reacting that was simultaneously inside the room and within the body. I didn’t have time to pause to think about it, so I let it go on, throwing itself at the walls like the high-frequency sounds in that concrete house until it fragmented into a patch of twinkling little pieces, little thieves, little bastards that moved between the concrete and the flesh bodies. Then I realized: this was a smell. Garlic! Heavenly garlic. A spray of its juices. Killing it. It was splashy and vulgar, as if when we say let there be light, then there was light. Though not God’s light, but the wet shine of saliva and tears, that moist pink shimmer on mucous membranes shared between our nasal passages and lungs.

After the performance, I found out that episode was HUANG Dawang peeling garlic in the audience. This was possibly my most psychedelic experience in Taipei.

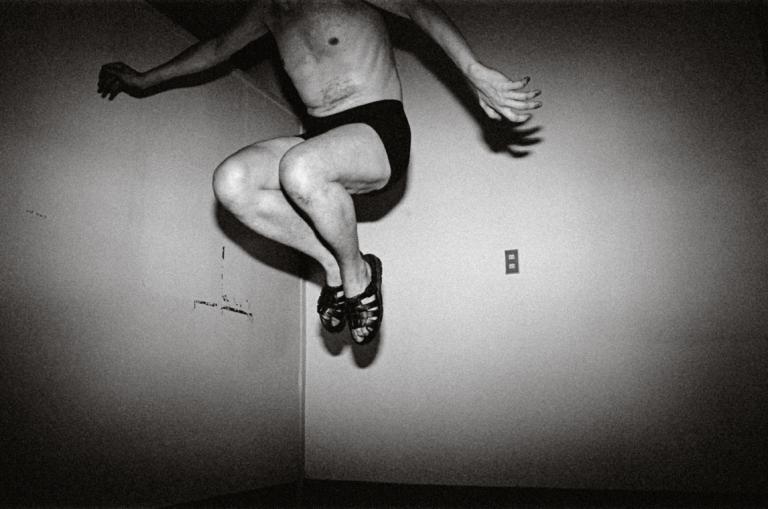

Then there was that time he described how, when watching a performance, he would be present in the performance space as neither audience nor performer, but in a third role. At one show, I saw him lying prostrate on the ground, lifting his upper body toward the stage and extending his gaze from this position like a sculpture. He was neither stationary nor was he a focal point. He simply existed in that space. His silent presence changed the gravitas and gravitation. Suffice it to say that everything was subtly changed and increasingly altered. His stony-faced absence of intention and expressionlessness only intensified his presence and added to the temporal-spatial dimensionality of the performance.

Thinking back on the pedigree of the garlic light on that night, there was a presence of political attitudes reminiscent of Wu Zhong-Wei’s primitive weapons from Treasure Hill; of Lin Chi-Wei’s Tape Music (or Sound Intestines); of the chaos that reigned over the Post-Industrial Arts Festival, LTK Commune, and Zero and Sound Liberation Organization; as well as of the avant-garde art/political activism behind the Good Student Movement; and of fragments of dialogue (on social media) that are now emerging at Kandala. This could create a landscape for sound and modernity or for sonic modernity – a challenge that LIN Chi-Wei posed in his book Beyond Sound Art. I am a willing reader and look forward to enjoying the fruits of others’ research one day. But experientially speaking, this pedigree has long dispersed itself outward from the role of being neither audience nor performer; it exerts its influence and destabilizes the fait accompli.

A good friend with revolutionary tendencies commented that he doesn’t see the impact of Dawang’s work (Nagashi in Bedroom, Noise, etc.) I think he actually touches on the core inconsequence of garlic: that noise no longer has a climax, including the climax that migrated from free-form jazz into boisterous cacophony. Remnants of Wagnerian romanticism are no longer there, merely squirming in silence. As far as his work goes, it seeks neither success nor confirmation; but continuously droops and implicates others. Revolution in the traditional sense is not present, nor is there a brilliant subjectivity. However, those bodies that have been stimulated will tremble slightly, twitch violently, and harass the expectations of good friends in mutual response.

I’m grateful, Dawang.