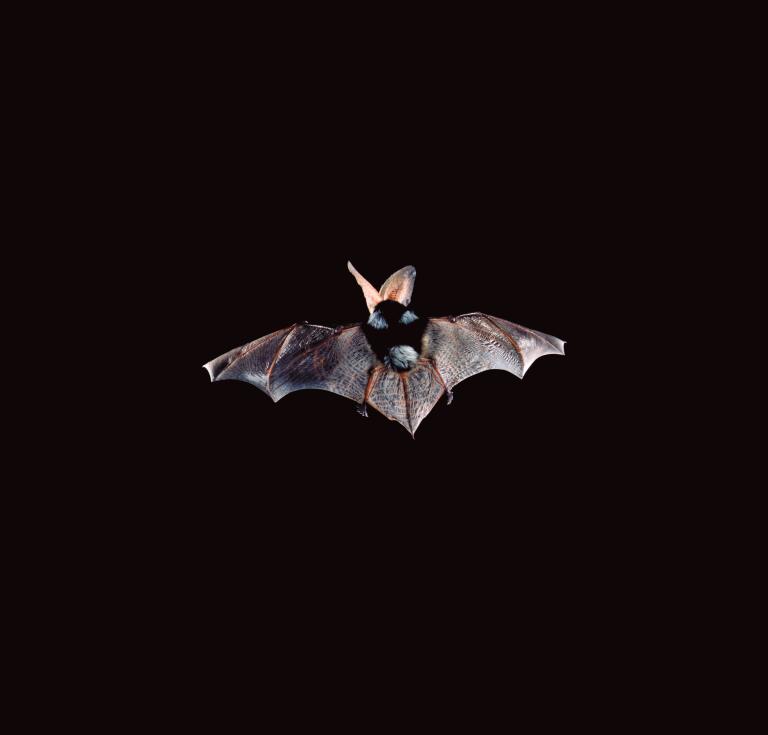

In 2013, I wrote an article for White Fungus called “In Praise of Bats.” The editors gave me the freedom to express my unbridled passion for Chiroptera: the order of mammals otherwise known as "bats." That article kick-started research that culminated in the book Bat, part of publisher Reaktion’s much-loved Animal series. I crammed that book, which came out in 2018, with as much information and as many images as I could. Of course, post-publication, I continue to find more bat imagery in art, poetry, and novels, and I wish I could write another book to do justice to this batty influx. Sadly, however, the joyful aspect of such a book would be outweighed by the bad press the animal has received since the outbreak of Covid-19. And even when humans aren’t threatening to exterminate bats in misguided pre-emptive strikes against zoonotic diseases, the climate crisis threatens them worldwide, especially along the east coast of Australia.

I am writing this article from Melbourne, notorious for being the world’s “most locked-down city.” As Covid-19 was starting to spread around the world like wildfire, Australia was literally being scorched by the Black Summer bushfires of 2019–2020, which saw animals, including bats, dying or displaced in their billions. But before I attempt to address such heartbreak, I want to spend some time celebrating bats

I have a file on my computer called “Further Bat Notes” for my mythical future bat book, which, like a B-grade film, might be christened Bat, the Return. This book would include the formidable jade mask of the Zapotec bat god held in Mexico’s National Museum of Anthropology. It would feature quotes from two beautiful poems by Australian poet Judith Beveridge. In “How to Love Bats,” she asks the reader to “try to find within yourself / the scent of a bat-loving flower.” [1] In “Flying Foxes, Wingham Brush,” dedicated to the late Deborah Bird Rose, Beveridge says bats are “as chatty as children fuelled / by afternoon sugars. They hug themselves lightly, / closely, the way tree-lovers hug wood.” [2]

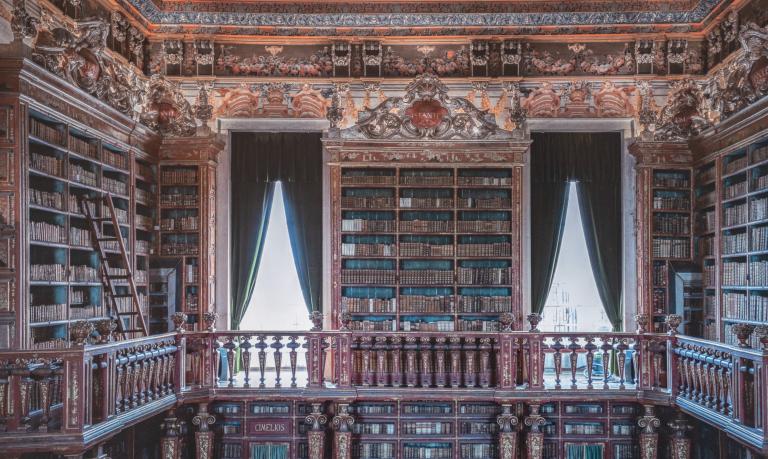

In my next bat book, I'd be sure to recount how the picturesque Biblioteca Joanina at the University of Coimbra, Portugal deliberately allows a colony of small pipistrelles to roost behind bookshelves in exchange for their insect-eating services. I might mention some strange sculptures by British artist Douglas White, who found that banana peels, when left to blacken and dry, can be used to fabricate leathery wings for sculptural bats. White made these works as a kind of homage after seeing a dead bat on the pavement in Melbourne, right after his father’s death. I'd see if Yuin-Monaro woman Gina Bundle would allow me to share an image of the incredible possum-skin cloak she’s been working on that features colourful flying-fox decorations on its interior side.

And I'd try to find out more about Jean-Michel Basquiat’s one-eyed bat symbols, often seen in tandem with the word MEMBER©. Member of what? The Justice League? The cyclops bats have one eye like the eye of the pyramid on the American dollar bill, like the all-seeing Eye of Horus. As I wrote in my original article, bats are associated (incorrectly) with blindness, but they are also notable for their uncanny ability to navigate in the dark.

In Bat, the Return, I would reflect that while my first bat book quoted the Samoan novelist Albert Wendt on the sexual properties of the flying-fox and their connection to the traditional Samoan pe‘a tattoo, at the time, I was ignorant of the wonderful bat imagery in another Samoan novelist’s work. Sia Figiel's Where We Once Belonged (1996) features phrases such as “bats lived in her armpits, in the crotch of her panties,” which is how the narrator characterizes her nemesis —who eventually becomes her lover. [3]

In spite of the brilliant diversity of all this imagery, since the publication of Bat, things have only gotten worse for real-life chiropterans. In December 2018, Australia-based ethnographer Deborah Bird Rose, one of their greatest advocates, passed away. She was working on a book about bats called Shimmer: Flying Fox Exuberance in Worlds of Peril, which was released posthumously in February 2022. Her last few articles were about flying-foxes, and they were stunning, oscillating between her deep love for the animals, their liveliness and beauty, and the suffering they endure — from being shot, abused by brutal council-sanctioned eviction tactics, and decimated by heatwave events. [4]

I almost witnessed a die-off event firsthand in Melbourne on December 20, 2019. The temperature was over 43 degrees Celsius: the point at which flying-foxes start dropping out of trees to their deaths. The colony of around 25,000 grey-headed flying-foxes at Yarra Bend Park was in dire straits. I tried to offer my services to a team of volunteers but was turned away at the gate. Although I'd had the requisite rabies shots to handle bats, I hadn’t had my titer level taken — to test my degree of antibodies — so wasn’t deemed fit to be near the heat-stressed mammals.

Later, I heard 4000 bats died that day, in misery and agony, as desperate humans sprayed them with water. A few days later, a friend sent me a powerful article by contemporary historian Shannon Woodcock about her experience trying to save flying-foxes during a heatwave in rural Victoria a year earlier. It’s a raw, painful must-read. Similarly, in the 2020 documentary The Weather Diaries, director Kathy Drayton worries for her teenage daughter, who is inheriting a world of ecological devastation, as she films flying-fox mothers and young in heat stress events. Volunteers care for the bats but can only help a few at a time. It is devastating viewing.

Forest fires in eastern Australia were already rampant by December 2019, and they continued to burn throughout January 2020. The fires up and down the east coast occurred in flying-fox breeding grounds, feeding grounds, and along migration routes. Traditionally, flying-foxes are key reforesters after such fires — spreading seeds from native trees wherever they go and pollinating eucalypts. With Covid-19 following hot on the heels of these ecological disasters, there was little opportunity to fully evaluate the damage done to these ecosystems, including those affecting bats or affected by the lack of bats.

Of course, Covid-19 itself turned out to be yet more bad news for bats, as it was immediately rumoured to be connected to horseshoe bats being sold at a wet market in Wuhan. Headlines all over the world automatically repeated this theoretical source of the novel coronavirus as gospel truth. I was immediately skeptical, because in my research for Bat, I'd seen the same pattern occur with other zoonotic diseases, where bats got the blame prematurely and media headlines reiterated unproven connections. In these instances, when subsequent test results proved inconclusive, the media didn’t produce grand headlines announcing “Bats Exonerated!” or “Bats Safer Than Your Dog!” They stayed quiet on the subject of bats altogether until the next zoonotic frenzy.

I looked to that bastion of bat advocacy, the founder of Bat Conservation International, Merlin Tuttle, and sure enough, he had many things to say about the real plague of these extraordinary times: sensationalist journalism. [6] Even well-meaning articles that emphasize the positive role bats play in ecosystems often recycle information about bats as "special" reservoirs for zoonotic diseases. In fact, a recent study shows that bats are no more likely to harbour diseases than other mammals, but they are disproportionately sampled by virus hunters. [7]

Tuttle has observed countless traditional societies living side by side with bats (not to mention eating them) without succumbing to any of the diseases that these animals supposedly harbour. Surprisingly, Tuttle advocates for the hunting and eating of bats (within reason), precisely because if they are seen as useful, they are more likely to be defended. While bat-eating is a little hard for me to swallow, when Yorta Yorta and Dja Dja Wurrung artist Tiriki Onus spoke at the launch of my book, he not only noted the importance of flying-foxes for the environment but also that they taste pretty good — because “they eat so much fruit, it’s like they come pre-marinated.” [8]

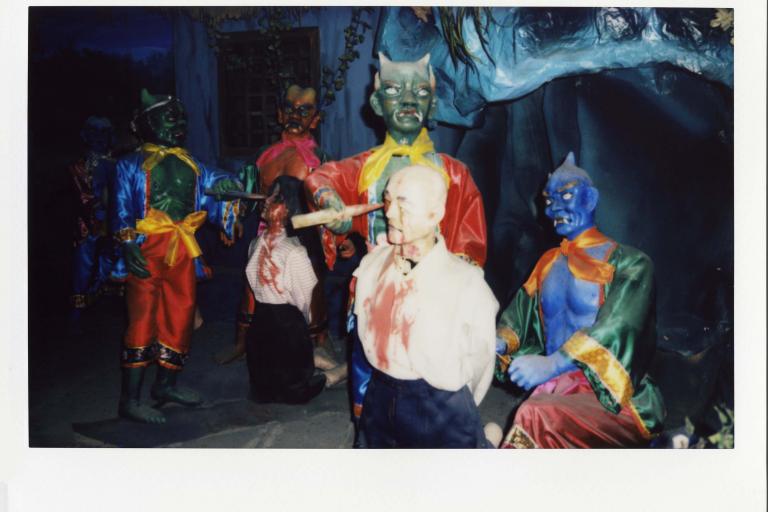

A friend living in Hong Kong sent me an article from the South China Morning Post at the end of May 2020, featuring images of posters in Guangzhou warning against the consumption of wild animals. One of them depicts a stylized bat wearing a face mask with a hole in its stomach. My friend contacted her friends in Guangzhou to make sure she had interpreted the poster correctly — the hole in the bat’s stomach symbolizes the fact that it’s been eaten, and a red strike-through circle surrounds the bat, warning against its consumption. Despite this grave message, the bat is pretty and decorative, with beautifully ornate wings.

Bats have traditionally symbolized good luck in China — one of the few places in the world where bat imagery is not dark and Gothic but full of whimsy and delight. Appropriately, my original article for White Fungus appeared in a bilingual issue where it was translated into Mandarin. I wonder if bats will continue to be emblems of good luck in China, but even at the height of the pandemic, a gentler view of them seemed to prevail in the detailing of this public health poster.

The pandemic has done nothing for the human view of flying-foxes in Australia, in spite of their having no link whatsoever to Covid-19. As soon as the suspected origins of the virus were reported, people here were calling for the eradication of bats, including the right-wing media commentator Prue MacSween referencing “Greenies’ love affair with bats” on Twitter and bizarrely accusing them of causing an AIDS-like virus in koalas. As scientists were quick to point out, koalas rely on bats to reforest the eucalypts they eat.

Bloodlust for the extermination — or at least eviction — of flying-foxes was soon directed at the very camp in Melbourne that had already suffered a significant die-off in December 2019. Residents of the affluent white suburb of Kew lobbied Tim Smith, their local Liberal Party MP, to get rid of the camp; he seemed only too happy to support their erroneous fears. Again, thankfully, scientists weighed in, but in some parts of the globe, residents took the law into their own hands, and there were reports of bat culling in India, Cuba, Rwanda, Indonesia, and Peru. [9]

These two (not unrelated) issues — the blaming of Covid-19 on bats and the attempted dispersal of flying-foxes — have both been brilliantly lampooned by the Guardian cartoonist First Dog on the Moon. [10] One comic contains a wonderful flowchart which asks the reader if they are angry, and if they are angry with bats, redirects them with arrows to where their anger should be pointed instead: the government.

The epic stupidity and cruelty of the Australian ritual of bat persecution was satirized superbly in Waanyi author Alexis Wright’s novel Carpentaria (2006) as the “Great Bat Drive,” which takes place annually in the fictional town of Desperance. “Every man had his chainsaw. Dozens revved. Mango trees — Baaaar- rrrrzip! Cedar trees — Raaaarrrrip! Poinsettia trees— Zipped.” [11] It all started when a bat bit a dog, and the dog turned rabid, after which countless legends circulated “about the effect of falling bat urine on human skin, of inhaling bat spit, or bodily contact with bat fur... Bats were high on the town’s list of things that can go wrong in the world. Everyone now believed bats carried a deadly disease. A disease which could spread to humans through the treasured fowl pens...”[12]

Tellingly, Wright comments that with all of this paranoia, nobody really saw the bats themselves anymore. “Showers of bat piss caught the imagination instead.” The white kids of neighbouring Uptown cry because they’re too scared to go to sleep in this “sad, sad, self-perpetuating sad town. Nobody had any idea how those kids grew up so fearful of the world and everything.” [13] Meanwhile, the Aboriginal kids are happily eating barbecued bat meat. In this scenario, the real virus is a fear of nature so profound that it poisons and incapacitates, or it leads to eradication, which in turn leads to extinction.

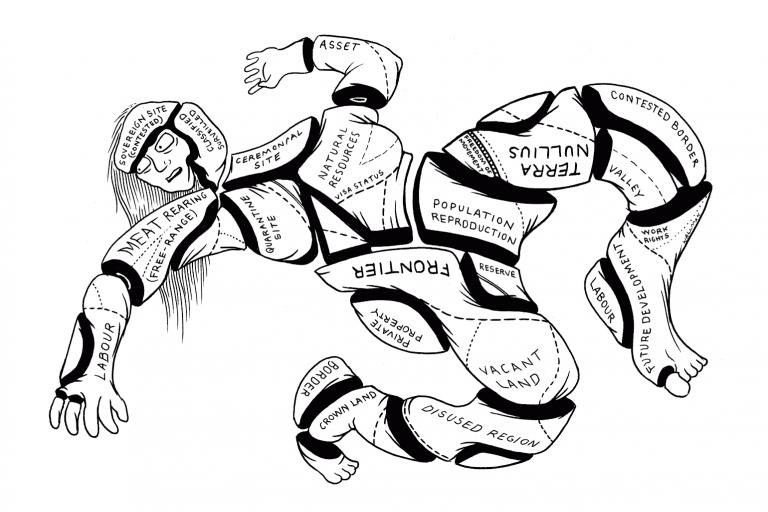

Brazilian anthropologist Els Lagrou writes that the Huni Kuin people of the Amazon attribute most illnesses to the fact that we eat animals, who then take revenge in the form of nisun, “headache and vertigo that can result in sickness or death.” This doesn’t make the Huni Kuin vegetarians, since plants, too, may be vengeful. Rather, one kills only what is necessary for survival via a series of negotiations, knowing all the while that “each action, each predatory act, unleashes a counter-predation.”

As Lagrou notes, it is not the fact that we eat pigs, bats, chickens, or pangolins that causes global pandemics. Rather, it is the extractive way in which global capitalism feeds on endless growth, creating the perfect breeding grounds and distributive networks for disease. [14]

Australian writer Laura Jean McKay’s 2020 novel The Animals in That Country seemed to anticipate a “zooflu” bringing the world to its knees. In the book, a pandemic is caused by a contagion with a peculiar side effect: People can understand what animals are saying. The animals don’t speak with human voices like Mister Ed, the talking horse. Rather, humans are suddenly able to comprehend the signals animals are already sending — through sound but also colour, gesture, and scent. The resulting cacophony drives humans wild with guilt over their horrific ignorance and arrogance.

After reading this book, I suddenly saw Covid-19 not as an example of zoonosis but of zoognosis. [15] That extra "g" signifies that animal life, indeed the whole lively planet, is full of knowledges, of mysteries — that all of us participated in once upon a time. Now we live lives of hyper-separation, alienated from our animal kin and earthly home. Zoognosis offers the key to a reawakening — sending encoded data from Gaia in the form of viral genomic sequences. The message is clear, if we have the humility to listen. [16]

We need to stop seeing ourselves as separate from nature, as if we ever could be. In a world of connection, there is no scapegoat. Such intimate entanglement is channeled brilliantly by American poet Sabrina Orah Mark, who, reflecting on the supposedly batty origins of Covid-19, notes that “every story begins with a bat.” This viral contagion of storytelling comes out as an incantation that is part witches’ brew and part jazz improvisation:

“So your mother is a bat, and my mother is a bat. I am a bat. You are a bat. My sons are bats. Every action we’ve ever taken is a bat. Every wildflower we ever picked is a bat. Sex is a bat and the soup you’ll eat tonight is a bat. This virus is a bat, and one day its cure will be a bat. Poems, even their crossed-out lines, are bats. Our lungs are bats. Death is a bat, and birth is a bat. The moon, the sun, and the stars in the sky are all bats. And when you cannot sleep at night that, too, is a bat. And when the president’s words fatten out of his mouth, those words are bats. And when you are afraid, your fear is a bat. And God, who created all the bats, is also a bat. And not believing in God is a bat, too.” [17]

This is zoognosis — a disease which enables the afflicted to remember that we are all diseased animals. We infect each other, and we affect each other, but that most infectious substance is, still, love — including, and especially of, the interspecies kind.

“I am a bat. You are a bat. My sons are bats. Every action we’ve ever taken is a bat. Every wildflower we ever picked is a bat. Sex is a bat and the soup you’ll eat tonight is a bat. This virus is a bat, and one day its cure will be a bat.”

As Australia unveiled its embarrassingly half-baked vision for a carbon-free future at COP26 in Glasgow, I returned to Yarra Bend Park to do some volunteer weeding and native planting near the flying-fox camp with Friends of Bats and Bushcare (FOBB). A few days earlier, there had been a terrible wind storm in Melbourne, and all night I kept imagining delicate bat bodies being hurled into buildings. Hundreds of bats did die, and rescuers said the roosting site at Yarra Bend was chaotic the next morning, as scores of baby flying-foxes had fallen to the ground and desperate mothers circled overhead.

Volunteers warmed the babies and gave them fluids before releasing them into trees where mothers could pick them up. Some mothers never came home. Those babies were given to foster carers, and two had been brought to the working bee by Megan Davidson, the FOBB secretary. At one point, Megan demonstrated the process of feeding the babies with a special formula. She asked how many of us were vaccinated. Everyone put up their hands, but then someone thought to ask for clarification: Vaccinated against Covid-19 or rabies? “Rabies,” she said, and we all laughed, as most of the hands came down. Only myself and one other volunteer were vaccinated, so we got to hold the babies.

It was magical to have this delicate, furry, and leathery being effortlessly latch onto my shirt, with her all-searching eyes, and exquisite, quivering snout. But it was also incredibly sad to see her tiny teeth exposed whenever she opened her mouth and cried, because she was crying for her mother, who hadn’t been able to weather the storm. And we know more storms and more heat stress events are on the way.

After holding this perfect creature, I continued weeding and found the decapitated head of another bat baby — no doubt one who had been downed in the storm, and then feasted upon by crows or other opportunistic wildlife. As painful as such a sight might be, I know predators are not the problem when it comes to flying-fox death. Habitat destruction, shootings, electrocution, and human-induced climate change are the problems. Some estimates say the grey-headed flying-fox endemic to this region will be extinct within eighty years.

The day I got to hold a darling baby bat was, appropriately, Halloween, the same day that the endangered long-tailed bat, pekapeka-tou-roa, was voted Aotearoa New Zealand’s "Bird of the Year," the first time in the sixteen-year competition that a bat had been nominated. [17] The next day, Tim Smith, the MP for Kew, who had postured about eradicating flying-foxes from Yarra Bend Park, resigned after being caught drunk driving. He had driven his Jaguar into the wall of a house where children were sleeping. His recklessness made me think of the fragility of the young life I had held in the park, and how the poor decisions of a powerful few could cause so much irreparable damage.

In 2022, some fantastic news arrived — the Victorian Government is constructing an AUD 180,000 sprinkler system to protect the Yarra Bend flying-foxes during heatwaves. Tim Smith, up to his old tricks, ridiculed the expenditure in a tweet, making his dislike for bats lucidly clear. It seems like a win for the flying-foxes, but even victorious moments like these are indicators of stress and suffering — the fact that the local government has been spurred to action is a reflection of the direness of the situation. Deborah Bird Rose insisted we face the suffering head on, but that we also open ourselves to the joy that bats bring into the world, that we embrace bats with a glorious assent. I imagine, for a moment, that each beat of their leathery wings is a loving hug, a literal embrace of life.

Footnotes:

[1] Judith Beveridge, Accidental Grace (Brisbane: University of Queensland Press, 1996),

[2] Judith Beveridge, Sun Music: New and Selected Poems (Artarmon: Giramondo Press, 2018), p. 181.

[3] Sia Figiel, Where We Once Belonged, Auckland, New Zealand: Pasifika Press,1996, p. 3.

[4] You can see Deborah Bird Rose perform an early version of her essay “Shimmer: When All You Love is Being Trashed”. The name of her bat book is Shimmer: Flying Fox Exuberance in Worlds of Peril.

[5] Shannon Woodcock, “Intimacy. Extinction. 2000 dead bats.” Overland, May 2019.

[6] See Merlin Tuttle’s Webinar, “Are Bats Really to Blame for the COVID-19 Pandemic?”

[7] Nardus Mollentze and Daniel G. Streicker, “Viral zoonotic risk is homogenous among taxonomic orders of mammalian and avian reservoir hosts,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, April 2020, 117 (17) 9423-9430; DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1919176117

[8] Buxton Contemporary, Melbourne, May 31, 2018. Tiriki is the son of the late artist Lin Onus, whose “Fruit Bats” sculpture from 1991 is one of the best-loved Australian artworks and one of my favourite artworks of all time. Tiriki also uttered the unforgettable phrase, “I love bats because they decolonize the landscape wherever they go.”

[9] Jason Bittel, “Experts Urge People All Over the World to Stop Killing Bats out of Fears of Coronavirus,” The Natural Resources Defense Council, https:// www.nrdc.org/stories/experts-urge-people-all-over-world-stop-killing-bats- out-fears-coronavirus.

[10] First Dog on the Moon.

[11] Alexis Wright, Carpentaria (Artarmon: Giramondo Press, 2006), p. 462.

[12] Ibid, p. 463.

[13] Ibid, p. 464.

[14] Els Lagrou, “Nisun: The vengeance of the bat people or what it can teach us about the new coronavirus.”

[15] The neologism ‘zoognosis’ melds the Greek ‘-gnosis,’ meaning ‘knowledge,’ and ‘zoo-’ for all animal life.

[16] See my article “Zoognosis: When Animal Knowledges Go Viral. Laura Jean McKay’s The Animals in That Country, Contagion, Becoming-Animal, and the Politics of Predation” in Animal Studies Journal, 2021, vol.10, no.1,pp. 30-56,

[17] Sabrina Orah Mark, “The Fairytale Virus,” The Paris Review, April 6, 2020.

[17] The annual competition is held by conservation organization Forest & Bird and decided through online voting that is open to the international public.