The soundtrack is the creation of audio artist Stephen Vitiello, perhaps best known for releasing a record of unaltered recordings made by affixing contact mics to the windows of his World Trade Center studio just weeks before the towers were brought to the ground. This piece is the December installation at the sound gallery Diapason (run by Michael Schumacher, another audio sculptor). I became aware of it when I saw an oversize postcard — its incongruity leaping out at me — at another Manhattan gallery during a Christian Marclay performance.

The postcard features a photograph of Dolly Parton against a black background, along with the dates and address for the installation. Vitiello’s Dolly Ascending takes a segment of Parton’s recording of “Stairway to Heaven” and stretches it to the point of losing any connection with the source. It’s bright, ethereal, glistening, angelic even. It’s neither Dolly’s country nor Led Zeppelin’s epic rock. But it is gorgeously musical.

I wrote those words a decade ago, and that postcard has remained over my desk ever since, a reminder of the piece I was trying to figure out, the widespread Parton fascination I wanted to get to the root of so many years ago. I collected information. I worked it from different angles, trying to find a way to get to the essence of this thing called “Dolly”. The more I considered it, the more complicated it got. Here was this larger-than-life woman who stands not an inch over five feet tall and whose attributes — the voice, the hair, the bosom — are the stuff of legend. She’s easily one of the most successful women in show business, in any business, and yet, no matter how much it might make her the butt of jokes, she manages to remain a down-home millionaire.

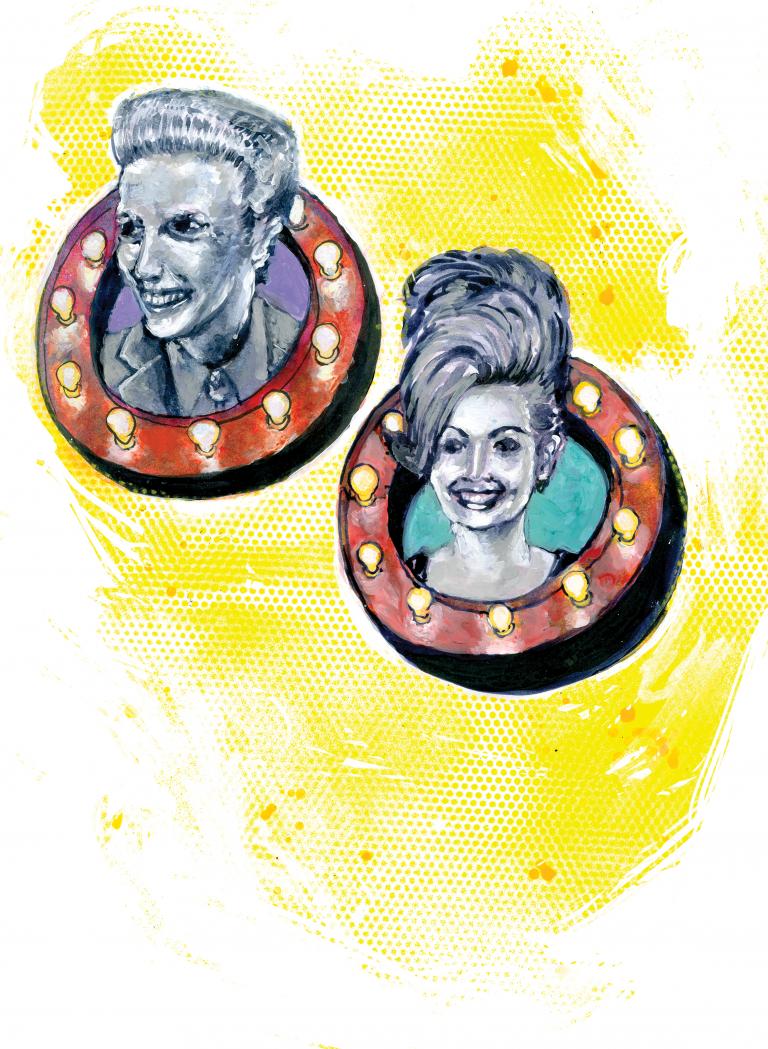

She’s a talented and immensely likable entertainer, one who clearly gets the key to longevity in the business. But she treats herself with more irony than does Vitiello. She can laugh at herself, and in interviews, likes to say that she looks like a drag queen (which is an understatement; gender aside, Mizz Parton is the Drag Queen Bee). She was part of a wave of older country artists who found freedom, maybe even inspiration, by being pushed aside by the industry at the end of the last century. Johnny Cash teamed with rock producer Rick Rubin, Merle Haggard signed with punk label Epitaph, and Parton began making genuine and solid bluegrass records, enlisting some of the best roots musicians around and, like Cash and Haggard, doing some of the best records of her career. At the end of 2015, a movie based on her signature song “Coat of Many Colors” — the first of a four-movie deal with NBC — earned huge ratings, and an opera about her fans was staged in lower Manhattan. In March of 2016, she announced plans for a tour of the United States and Canada to hit more than 60 cities, plus a new double-CD set. Dolly Parton doesn’t just remain vital; she is omnipresent.

The more I worried about the subject, the more I became convinced of two things: One is that, while she might be an easy target for ridicule, you’re not going to find a joke to make about her that she hasn’t already made herself. The second is that she might be the best-known and best-loved person alive today. It’s a bold claim to make, but I haven’t been able to think of anyone else so widely known and so rarely — if ever — disliked. Be it for her music, her movies, or merely her image, rare is the person who has no interest in her. She seems the last of a breed; Elvis Presley and Frank Sinatra were bigger ticket items, but they’re gone now. And in this media-saturated world, it’s hard to imagine anyone else ever occupying a global stage the way they did. Today’s superstars — Taylor Swift, for example — are niche artists by comparison.

It’s that popularity that makes Parton insusceptible to ridicule. You can make fun of her, but you can’t disparage her. You’ll never get Dolly’s goat. Even in the big, culturally elite city where I make my home, any mockery is served with respect or at least affection.

Perhaps the greatest of New York City hoity-toity takes on Parton dates back three decades when an effete and willfully strange New York artist gained unexpected national notice due in no small part to the nascent music video market. Laurie Anderson’s 1981 single “O Superman” — with its repeating “oh oh oh” vocal rhythm track and its neurotic monotone vocals — was the hit, but on the B-side, Anderson name-checked Parton. With a repeating toy-dog bark replacing the ohs, Anderson furthered her ruminations on modern life, and the hybrid of performance art and stand-up comedy on which she’s built a career:

It was a hilarious indictment of the selling of celebrity, coming on the heels of a five-year run that was probably Parton’s biggest string of commercial success to date. A crossover into the pop charts earned her more fans than she lost (no small feat there), starting with “Here You Come Again” in 1977 and peaking with the song and movie “9 to 5”. She appeared on-screen alongside Sylvester Stallone and scored a hit written and produced by Barry Gibb. But to ask what Anderson meant seemed beside the point. Like David Byrne during the early days of Talking Heads, Anderson purveyed a wide-eyed take on the culture of commerce. She didn’t sit in judgment; she allowed us to. She innocently asked who would be walking Dolly’s dog. We (in our intellectualized big-city way) knew (or thought we knew, or were made to think we knew) that the last thing Parton was ever going to do was to go back to the Tennessee mountains and walk some mangy mutt. Dolly, unlike Laurie at the time, was a superstar.

Anderson played on a common contempt for celebrity and, at the same time, a cultural love for Parton that ran deeper. In hindsight, it seems a little unfair. Anderson’s sympathies lie with the dog, but does Parton really deserve the condemnation? Anderson is playing the innocent, but we know her intention is to call Parton out. We can also easily imagine Parton giggling about the lyric. She comes out on top, possibly without even having heard the song. Her goat ain’t been got. A similar lyric about Stallone wouldn’t have had the same endearing quality.

I’ve long had a love for Parton, one that (as I suspect is true for most people) isn’t easy to articulate. On television in the early 1970s, she embodied (quite literally) the limited comprehension my young mind had about sexuality. She was, or they were, rather, a remarkable sight, bejeweled with rhinestones as if you might otherwise miss this tiny blonde with the 40DD breasts. I remember Johnny Carson telling her he’d give a week’s pay to look under her shirt. I was mortified, but Dolly laughed (squealed, really, as she does), and I thought I had caught a glimpse of swinging adult life, imagining a world where you could talk openly to ladies about their boobs at cocktail parties.

But my love for Parton wasn’t pure. Growing up in central Illinois — on the border of the Mason-Dixon Line and in the country of country music — and spending summers at my grandmother’s Tennessee farm (although in the dust bowl of the western end of the state, opposite the Appalachians where Parton came of age), all I wanted was out. I wanted to get to where art and punk and ideas thrived. And oddly enough, 30 years later, Dolly provided me a bridge between North and South, between city and country, and the artificial divisions between high and low art. After visiting the Dolly Ascending installation, I wrote Vitiello (who lives in Virginia) to ask him about his interest in Dolly Parton. I wanted to know about his motivations and, in particular, if there was any irony in his source selection. He wrote back:

“I listened to it expecting kitsch and found the performance to be really touching. There’s something about the roar of the crowd and her down-home response, too, which is hard to belittle. The band sounds like the normal old-session musicians, but she rises above them.”

Vitiello began working on his piece while in Italy, preparing an installation for the Sound Art Museum.

“I was staying at the American Academy in Rome, which is on a hill and very quiet at night. People in the courtyard all seemed to be talking about the Pope, who was on his deathbed.”

It was the perfect environment to consider Dolly the Christian songbird and her heavenly ascent.

“I think place, state of mind, time of day all affect what one makes. For me, it seems so clear so often that what I’m trying to create is always some sort of response — to the material but also to the immediate environment. Sometimes a tense situation can bring on a successful result as well.

“The first night, I couldn’t sleep and started playing with the live track, adding delays and convolving (using the sound of the bell as a reverb across the whole track) the sound of a bell onto the voice and using various forms of time-stretching. I worked on it from about 11 pm until 4 am. I did the same thing the second night and ended up with three very long pieces. “Dolly 2” and “Dolly 3” have more recognizable sounds from the recording than “Dolly 4”, which is what I used at Diapason. That one is the most abstracted and ethereal.”

Abstract and ethereal it is, and far removed from the blonde manes of Dolly Parton and Robert Plant. What wouldn’t seem to have been an inspiration for Vitiello to select the song for his cloud soundtrack, and what assumedly was for Parton deciding to do the song in the first place, was Plant’s beyond-famous lyrics:

I’m not sure I ever really understood the first verse of Led Zeppelin’s song, or if it even makes sense. But who more than the shimmering millionaire herself might it describe? All that glitters is not gold, we know. There are also sequins and rhinestones, and sparkly lipstick. But can Parton get whatever she wants whenever she wants with just a word? It’s hard to imagine not. And materialistic? With her money, I’d be too — although I’m not sure I’d open a theme park with 27 stores. Is she likely to be turned away at the pearly gates? I don’t think so. We can almost imagine Parton deciding to sing the song without understanding that the protagonist isn’t supposed to be on the right track toward salvation. Oh, it makes me wonder.

Vitiello wasn’t the first avant-gardist to alter Dolly’s music. In 1988, John Oswald — the prince of plunderphonics — warped Parton’s version of “The Great Pretender” and created a gender-identity argument befitting the Drag Queen Bee. The liner notes to the Plunderphonics set (released on Negativland’s label Seeland) elaborated on the psycho-sexual effects of altering Dolly’s voice:

“‘Pretender’ takes a leisurely tour of the intermediate areas of Ms. Parton’s masculinity. This ç, an unaltered transition between the ‘Dolly Parton’ the public usually hears and the normally hidden voice, pitched a fourth lower. To many ears, this supposed trick effect reveals the mellifluous male voice to be the more natural sounding of the two. Astute stargazers have perceived the physical transformation, via plastic surgery, hair transplants, and such, that make many of today’s media figures into narrow/bosomy, blemish-free caricatures, and super-real ideals. Is it possible that Ms. Parton’s remarkable voice is actually the Alvinized [chipmunked] result of some unsung virile ghost lieder crooning these songs at elegiac tempos, which are then gender polarized to fit the tits? Speed and sex are again revealed as components intrinsic to the business of music.”

On her 2002 album Stifled Love, the British sound collagist Vicki Bennett — aka People Like Us — created a track of stuttered “ums” and “uhs” called “Dolly Pardon”. The album comprises love songs chopped and altered, as Bennett told me, “before people can express themselves properly”. Like Vitiello, Bennett expressed to me a sincere admiration for Parton and her work:

“I love Dolly Parton because she is a strong woman who has directed her own career, yet remained a kind of friendly human being (or at least that is how she comes across to me), and her music contains great spirit. I also like that she has a private life — she does her job but also appreciates that there is more to life than being well-known. I like sampling strong female figures of older generations, the ones who aren’t stupid. She’s particularly inspiring being a female since there aren’t that many who will persist in the way that a male can find more natural.”

A file of incomplete thoughts and interview notes sat on my hard drive for the ensuing years, occasionally revisited but never finished. I was fascinated by how these artists working outside the mainstream seemed to embrace Parton even while using her work to their own ends, but it was somehow incomplete. I eventually realized that I was ignoring half my identity and, as such, half the reason I was trying to write about her. I was just collecting representations of Dolly, filters through which she could be viewed, which could also be fitted (and it chills the Tennessee DNA coursing through my blood to say it) as somehow representative of my East Coast, Ivy League, avant-garde, culturally elite lifestyle. A Soviet potato farmer would better understand what Dolly’s about than anyone might through the construct in which I’d wanted to house her.

Part of this realization came from seeing Tai Uhlmann’s 2006 documentary For the Love of Dolly. The film is less about Parton herself than it is about her fans. Uhlmann followed four sets of Parton fans as they prepared for an annual pilgrimage to the opening day of Dollywood. It shows the sincere dedication of her fans, but perhaps more to the point shows that the relationship is not entirely one-sided. It’s one of idol worship, of course, but Parton receives her public with generosity and grace, accepting their handmade gifts, posing for pictures, and remembering many by name. I met Uhlmann at the Brooklyn Academy of Music after the premiere (more cultural elitism there) and was so taken with the film I arranged for subsequent screenings at Anthology Film Archives in Manhattan and the WFMU Record Fair, and got the DVD as soon as it became available. During the course of several conversations with Uhlmann, I told her about my floundering essay and about how her film made me realize I had failed to address the phenomenon of Dolly Parton directly. She encouraged me, strongly and with a warm smile, to make the trip to Dollywood, which eventually, I did.

It turns out Laurie Anderson was wrong. Dolly did go home again, only a few years after “O Superman” was released, and she brought with her the mindset of the music industry. To city folk who might romanticize mountain life without even wanting to spend much more than a couple of hours without an indoor toilet (as Parton is fond of saying, her childhood home had two rooms and running water “if you were willing to run to get it”), that might sound like the spoils of capitalism, but the economic vitality she brought to her old corner of East Tennessee shouldn’t be underestimated.

Dollywood was created in Pigeon Forge, Tennessee, on the site of another amusement park that was struggling to stay alive. First opened in 1961 as “Rebel Railroad”, the park was reinvented as “Goldrush”, “Goldrush Junction” and “Silver Dollar City, Tennessee” before Parton became a co-partner in the facility with amusement park developers Jack and Pete Herschend in 1986 and rechristened it “Dollywood”.

Like Silver Dollar City, the corner of East Tennessee had its financial struggles. In her autobiography Dolly: My Life and Other Unfinished Business, Parton remembers her adolescence in the area of Pigeon Forge:

“We used to cruise Gatlinburg and Sevierville, circling the Tastee-Freez, flirting with the boys, and singing. I’d always carry my guitar. Most of the girls around there were kind of shy, and I would always manage to attract the boys with my singing and joking.”

Fond memories notwithstanding, it was an economically depressed area. Parton not only went home again but, through her business venture, became the largest employer in the community.

While Dollywood itself is a low-key and perhaps surprisingly pleasant park, the surrounding area is rife with souvenir shops, record and musical instrument stores, and dinner theaters featuring such entertainments as a Hatfield and McCoy re-enactment. With the inclusion of several miles of satellite business outside of the park, Parton’s economic impact on the area is, perhaps, inestimable.

Like her amusement park, Dolly exists on both sides of the wall that separates reality from artifice. She can project genuine emotion through the sap of her songs. She manages to radiate even through cosmetic surgery.

Parton, her music, her movies, and her theme park all shine through the crass commercialism of big business. Dollywood is a remarkably pleasant place to be. It’s filled with trees and music and instrument-makers. The restaurants have relatively non-gaudy signs, and the rides are cleverly hidden behind the tree line. It’s an oasis amidst the miles of immodest merchandising for which it’s responsible. It’s a multimillion-dollar temple for her, made by her, and yet somehow, like Parton herself, manages to seem humble.

Parton has made an enterprise of singing about herself, portraying herself, and being herself. With the theme song from “9 to 5” being a notable exception of fiction in her canon (she no doubt works her ass off, but she’s never clocked hours in a secretary pool), Parton has probably recorded more first-person songs than just about anyone — the abysmal “Coat of Many Colors”, sure. Still, the examples are endless: songs about fame, songs about Tennessee, songs about growing up poor. Take, for example, this excerpt from “Better Part of Life”:

Ultimately, that self-assuredness might be what gives Parton her appeal. There are too many singer/songwriters, busty blondes, and mediocre actresses for any of those — even all three together — to explain her popularity. What Parton has is a deep belief in herself and an ability to exude that quality. In her autobiography, she tells the story of announcing that she would be “going to Nashville to become a star” during her high school graduation ceremony. As she remembers that day:

“The entire place erupted in laughter. I was stunned. What were they laughing at? I remember thinking to myself, ‘They don’t know. They just don’t know.’ Somehow that laughter instilled in me an even greater determination to realize my dream in a kind of ‘I’ll show them’ way. It is very likely that I might have crumbled under the weight of the hardships that were to come had it not been for the response of the crowd that day.”

The next day she was on a Greyhound bound for Nashville. Within three years, she was being seen in homes across the country as a featured performer on The Porter Wagoner Show. The duo, Wagoner and Parton, had 21 charting singles between 1967 and 1974, before Parton set off for a career of her own, becoming the most powerful woman in country music, if not in show business.

Dolly Parton turned 70 in January of this year and remains an icon — perhaps the last one — of genuine American superstardom.