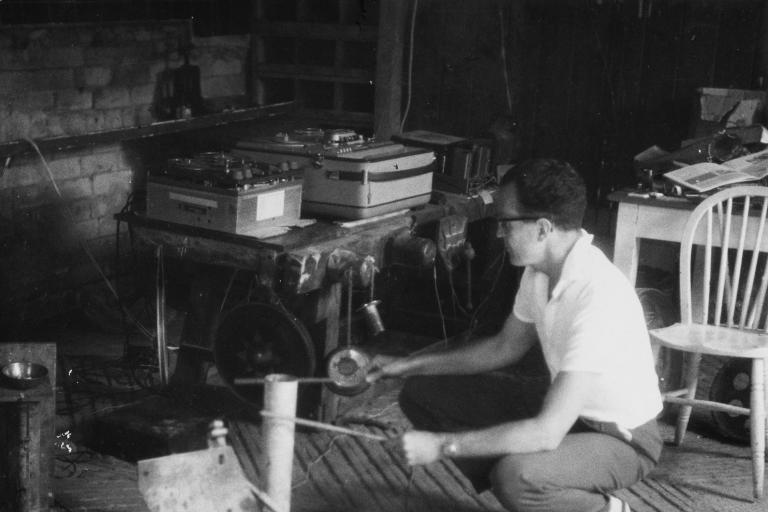

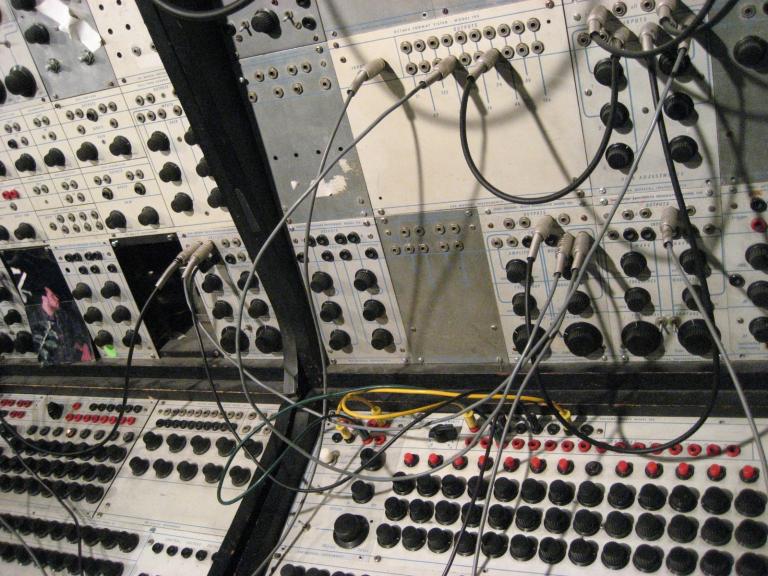

Buchla, a former part-time NASA engineer, built the synthesizer according to Subotnick’s specifications. Crucially, it had no black-and-white keyboard or any traditional inputs representing the history of music. Subotnick believed these would only lead the user to create old music with new technology.

Instead, the composer wanted to create what he calls a “new new music.” This was “Day Zero,” he believed, in the evolution of music. He also wanted the synthesizer to be accessible to anyone, regardless of their musical background. Subotnick saw this new technology as holding the potential to radically democratize high culture and foster a new musical literacy.

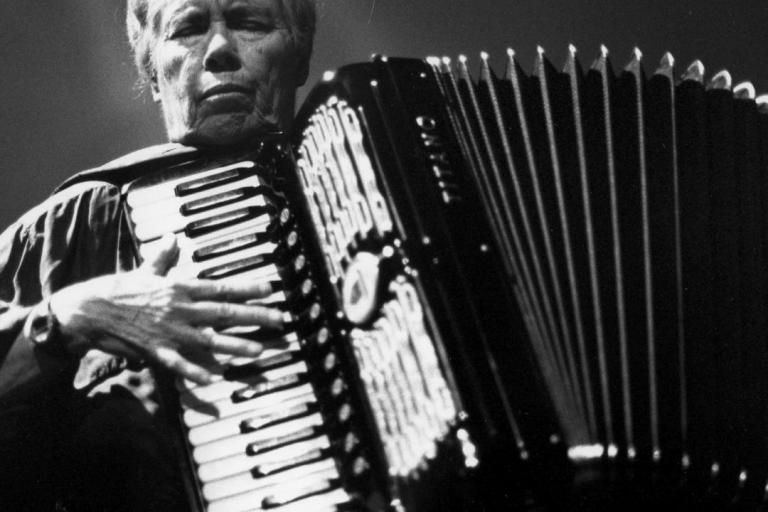

In 1966, Subotnick began work on his seminal work Silver Apples of the Moon for Nonesuch Records—the first electronic music composition commissioned for the LP format. While creating this revolutionary music, he received visits to his Bleecker Street studio in New York from bands, including The Grateful Dead and Mothers of Invention.

Silver Apples of the Moon was released the following year and became a surprise commercial success, topping the classical music charts. The former clarinetist and classical music prodigy suddenly became an unexpected, and at times reluctant, celebrity. Twice, Subotnick turned down requests to appear on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson, concerned that his music would be turned into a gimmick and used merely as a prop.

Electronic music today is unthinkable without Subotnick’s contribution. While appreciation for high culture may not have grown as much as he had hoped or anticipated, his work has nonetheless made a profound impact on popular culture. His influence has been cited by musicians such as Kraftwerk, Daft Punk, and Paul McCartney.

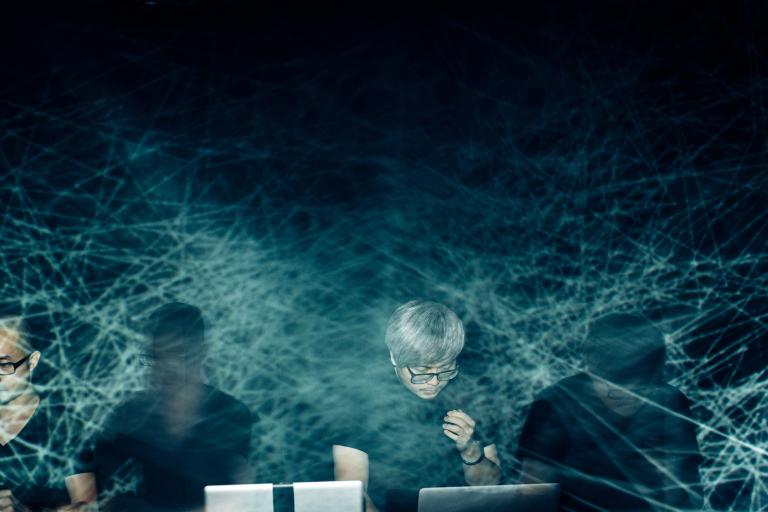

In December 2020, at the height of the COVID pandemic, Subotnick joined Paul Holdengräber on his podcast The Quarantine Tapes. Produced by dublab and Onassis LA, the podcast chronicled shifting paradigms in the age of social distancing. Holdengräber phoned Subotnick to hear how he was adapting to life under lockdown. The illuminating discussion covers a broad swath of the composer’s life and thought. The text has been edited for clarity and length.

Morton Subtotnick: Hello.

Paul Holdengräber: Hello, could I please speak with Morton Subotnick?

MS: Yes, this is he.

PH: Hello, Morton. This is Paul, Paul Holdengräber, calling you from The Quarantine Tapes. I’m so very delighted you could take time to speak to us today. Thank you so much.

MS: You’re welcome.

PH: Tell me, where do I find you? And if I may ask, what have you been up to in these now six months of quarantine?

MS: Has it been that long? I thought it was my whole life.

PH: Doesn’t it feel like that?

MS: Yeah. No, we’re up in Westchester, near Peekskill on the Hudson.

PH: And what have these six months been for you? What have you been doing, and maybe, what haven’t you been doing that you wish you could have done?

MS: Well, eighty-five percent of the time, I’m doing what I always do: I'm in my studio working. I have a lovely view of trees from here, and so that part has been pretty steady in terms of my work. Not being able to go anywhere is another situation, but I would say seventy-five percent of my time is doing exactly what I’ve been doing most of my life.

PH: Sometime, Morton, in the 1950s, it dawned on you that you were living through a pivotal turning point in the history of music. What was the nature, if one can say, of this epiphany? You compare that moment actually, so interestingly, I found, to what it might have been like to be at the beginning and the origin of the printing press.

MS: Yes, that was the end of the ‘50s, and I realized that at that point in time, we were already a little bit technical, technically savvy. We had radios, of course, but most of the history of the human being with music had been listening directly to someone playing, or playing it yourself. There was no other way to do it as far back as maybe 45,000 years, at least, because that’s when we got the first flute. That’s a long time.

And the same, of course, was true of the printing press, and until the start of writing. I guess they had tablets they could send around, but the printing press made reading what someone wrote available worldwide, and it changed lives. And it seemed to me that the same thing was going to happen with music.

I didn’t know exactly how it was going to be—probably with recordings, with vinyl records. I really didn’t know what would happen with the computer and so forth, but it seemed to me like an equivalent: suddenly, people in the middle of—I don’t know where, out in Borneo or wherever it’s remote—would be able to hear music. They would be able to hear the Berlin Philharmonic. Only people who lived in Berlin were able to hear the Berlin Philharmonic, if you could afford it. And it was cheap, too.

PH: You mean records were cheap?

MS: Yeah, they were cheap—they were under a dollar, the equivalent of three or four dollars today. But they weren’t very good; you could hear it.

PH: When I read about you comparing it to the printing press, it brought back to mind reading these wonderful books about the origin of the printing press and also the oral tradition. You might be familiar with Walter Ong, who wrote so beautifully about the theme.

I’m wondering if you can bring us back to that moment—a little bit later in your life—at Mills College in the early 1960s, where you worked on the development of the first analog synthesizer. You said you wanted to create—and I love this—“an electronic music easel, an object similar to what they’d be using in a hundred years.”

MS: Well, I thought one hundred years because it took that long for the printing press to get real books out to people—that was a hundred years. But I still feel that way.

I was playing part-time in the San Francisco Symphony at the time and also going on concert tours with a chamber music group—playing concertos and things like that with orchestras. But I realized two things: One was that music really speaks through the ear. If you’re a musician, it speaks in different ways through the body and so forth, like body memory. But most people hear music.

And I realized that this music we’re hearing is influenced by oral tradition. I say that because we did write music, finally, but that didn’t help anyone; they couldn’t hear it. That’s why I mentioned the ear.

PH: Right.

MS: Music enters through the ear, so musicians can play it from written music—and that is something—but it wasn’t the big turnover that the printing press experienced. And I realized that—it was complicated. I’m pausing because it’s a complicated notion.

A person like myself, who started music early—maybe at age six or seven—and pretty much got addicted to it, playing music all my life for hours a day and learning about music, that was it. So by the time I was seventeen or eighteen and getting ready to enter the world, I had already been playing professionally since I was fifteen or sixteen. It was just part of me.

But most people don’t. I mean, the majority of people don’t come near that kind of experience. So those people—the majority of people—were sort of stuck at seventeen or eighteen. You can’t decide, I don’t think, to suddenly become a concert pianist at eighteen years old. I mean, you could decide to do it…

PH: Yes.

MS: But it’s a very remote possibility at that point.

PH: It won’t materialize simply because you’ve decided.

MS: That’s right. I mean, it’s all about the body—energy and memory that you develop over all those years. Two things occurred to me that were similar to the printing press. People who were addicted to music in the traditional way, from playing an instrument, would probably continue that way. The technology was not going to change much for them. The good thing for those people is that they are good musicians. The bad thing is that you can’t take on new things. You can’t easily take on new things at that point.

But the majority of people would be getting it maybe for the first time. They’d be getting interested in music. The dichotomy for me at that point—and the reason I gave up playing the clarinet, left the concert world, and devoted myself to this other—is that people would be getting music through what we call popular music. That’s why it’s popular: because people listen to it. It’s not something that requires years and years of experience. It’s relatively straightforward, and it’s popular.

And so they’d be coming to it from there. We had the same kind of thing with the book when it first came. A lot of people felt this was terrible because people weren’t going to be reading the Bible—not in Latin or Hebrew but in every language, whatever the book was supposed to be in—and that was going to do some bad things. And it did democratize it, but it certainly caused a lot of problems as well.

PH: Yes.

MS: It’s a very difficult situation, and I felt that the beauty of what was going to happen with music was also problematic—that people were already illiterate musically, and this would make them literate only through the ears.

So I have a Schwinn bike, and one of the things I’m doing during this quarantine is I’m riding seven miles a day on it. I’m listening to a book and a number of things. Right now—probably for another five, six, seven days; it will be about two weeks in total—I’m listening to The Art of the Fugue as I go, and I’m watching mountains and grass and going through it on my computer as I do this.

PH: How glorious, how glorious.

MS: Yeah, I know it. And you know, I was thinking about that this morning. When you get to a double fugue, it’s just—it makes my heart race and my head opens up. Then I was thinking—reflecting back on those early days—it’s very unlikely that a person who didn’t grow up with as much literacy as I did would be able to hear that and know that’s happening. So, it was a complicated thing.

At that point, back in the late ‘50s and the early ‘60s, when I was working—actually, I started this in ‘63 with Don Buchla—I wanted to create something that was not a musical instrument. I like to call that now a traditionally based musical instrument, where you play. The only thing you can do on it is play the music similarly to everything that’s been done with it before.

If you have a black-and-white keyboard, it’s basically a keyboard instrument, and you have to tune it. So, whatever key you’ve got it tuned to, whatever tuning you’ve got, it’s going to give you that kind of music, and you have to learn to play it. I mean, it’s a crazy notion, but if you give someone a traditional instrument that connects to something, you still have to learn the thing to play it. So, I thought of that as something I’d call making “new old” music.

PH: Yeah.

MS: And what I was looking for was somebody at that age level—seventeen, eighteen years old, or younger—who wanted to create something musically. You could do that in paintings, but you can’t easily do it in music. So, that was the idea. I was going to have to place myself in order to make a “new new” music.

And perhaps, in time, if you had the right equipment to facilitate this, there would be some new new music—music that didn’t start at five years old but at eleven years old, or twenty years old, or thirty years old. It would be creative and have its own syntax, its own life.

So, I tried to place myself. This is going to sound presumptuous, but I thought of myself not as a composer—even though I was writing music then, more traditional pieces—but as a creative musician trying to make a new new music.

I was thinking of Berlioz. I was thinking of the grand pieces you could do. But I didn’t want to sound like Berlioz. I wanted to grow and find some language. I don’t know why, but I never really paid much attention to his background, although I know he got kicked out of the conservatory.

PH: Yes.

MS: In France, at one point. My guess is that he wasn’t quite as cool as some of the other people were—that he was a maverick of some sort, who came out of it because he certainly did a different thing than anyone else was doing at that time. And then odd people like Schumann would love him, but everyone else was saying, “What is this that he’s doing anyway?” So, that’s what I thought.

But I wasn’t really looking to make waves as a composer; rather, I wanted to help create this instrumentation—electronic instrumentation—that would show things you could do. I was positive—and for this part, I was completely right—that what would happen with this new technology is that people would want to get involved so they could make money. They would take what they knew about music, which was traditional instruments, and they’d make it electronically.

So, the first thing we’d have is a keyboard, and that was only because it was easy. If you wanted a trumpet—that did come later—as well as saxophones and clarinets, and other instruments, and finally string instruments. But those were difficult to make technologically, so the keyboard was the first. Then, certainly, the Buchla came.

“Silver Apples” was the piece that came one year before [Wendy Carlos' album] Switched-On Bach—luckily, because nobody would have listened to it otherwise. It is really a testament to how correct I was about what was going on—and that was my thought, a new new music that’s plagued me all my life. I still live with it. I listen to The Art of the Fugue and I wonder, in the new new music, what would be the equivalent of The Art of the Fugue? I’m trying.

PH: I’m just imagining you, Morton, bicycling those seven miles, listening to The Art of the Fugue, remembering your feelings about Berlioz, and also wondering: You’ve spoken about the need to see beyond electronic music, and I feel like that might be a life’s quest. I wonder what you mean by that. You’ve also said that technology should allow you to return to your inner self.

MS: You know, through technology, not beyond technology. I may have said beyond technology, but you need technology to do it. Well, I did it. I began doing it, starting with “Touch” in 1969. Around that time, I called Don Buchla and said, “I’ve made a big mistake.” I'd been thinking so much about painting that I was constantly telling him about using your hands—how we use our fingers and the different ways of pressing things and pushing things.

And I said, “I left out the thing that I’m actually best at—using, not my voice, but my breath—and I would like to use my voice and transfer that into the brush.”

So, he made me an envelope detector, which translated the amplitude of my voice, in addition to the touch things. I got really good at that; I still use that as a model. So, [vocalizes], I could take the very envelope of the amplitude and send it back into the electronics and make it go [vocalizes]—ah, well, I can’t sing; Dylan tried. I really perfected that by the late ‘70s.

I finally got “Until Spring,” and then “A Sky of Cloudless Sulfur” was the last one. That’s how I ended with the records and moved on to other places, and continued translating that in other ways. And I still work that way now. I have a wonderful breath controller that I use, which allows me to play the clarinet—practically, into it—not as a performance instrument, but rather as an entrance.

Instead of the brush, I have my mouth, my voice, which I can breath-stroke sound [vocalizes], you know, and then it translates into electronic sounds and moves through the room. Anyway, you get the idea. So that’s what I meant, and you actually can do it.

I think we’ll get better—that will get better—but you don’t get better at it unless someone needs it. Someone has to break that thing, and I’m writing a memoir and going to share—I’m trying to share like mad. I still teach lectures twice a week. I’m trying to make this known, and I’m releasing all the technology that I’ve done. Along with my memoir, there’ll be a website where you can come and download for free how to do all these things.

PH: That is so wonderful to hear, Morton. Really, how great. Both the memoir and what you’re going to share with the world in terms of technology. I want to bring you back again, if you permit me, to being even younger.

As a very young child, you were transformed by reading a biography of Mozart as well as several books by Stoic philosophers. What was it, Morton, about these books that opened your mind? When I read about this, it reminded me of the wonderful line by Frank Zappa, who said, “A mind is like a parachute. It doesn’t work if it isn’t open.” And what was it that opened you at that moment, with Mozart and the Stoic philosophers?

MS: I honestly don’t know. I was about eight, a little under nine years old.

PH: Amazing.

MS: And I don’t really know. I actually went through several years of psychoanalysis, but I still couldn’t tell you for sure. I don’t really know.

PH: This is your chance.

MS: And the pair, of course—well, I loved playing the clarinet. By the age of nine, I was already playing the Mozart clarinet concerto. Mozart and Brahms were the two composers who had music for the clarinet that I loved more than anything.

Reading the biography of Mozart—I don’t even know how I got it—but I can tell you it’s kind of odd. If my memory serves me correctly, what really opened my mind, and what I remember most, is that he was poor. He only lived to—I don’t know—thirty-some-odd years. I thought he lived to thirty; I know now he lived a little bit longer.

PH: Thirty-six.

MS: Yeah, but somehow the “thirty” rang in my head until later in life—I thought he had died at thirty. I even thought I was going to die at thirty, but I won’t bother with that story. You can read about it in my memoir.

I mean, the fact that he was a great musician and that the music was so beautiful didn’t open my mind. What opened my mind was that he was poor and died young. That triggered the notion that: a) maybe I could be a composer, and b) I’d better live my life as hard and fast as I can because I may die young.

And the Stoic philosophy—there was a kind of existential quality to it that meant you live your life. I read Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius, and I don’t know where I got it from—whether it’s from the books or just part of my memory bank that transformed it. But what I learned at that point was the meaning of life—and it never changed. You find out who you are; your duty is to find out who you are, what you are, and do the very best you can with that, and share what you do with other people. That’s what I’ve done my whole life.

PH: Not a bad lesson to learn.

MS: Not a bad lesson to learn.

PH: And not a bad lesson to learn when you find books in your parents' garage and read them for a year when you’re nine years old. You also met Stan Brakhage when you were both quite young.

MS: Yeah.

PH: To what extent do you see parallels between what he did in the realm of film and what you have done in the realm of music, and is he still with you?

MS: Yeah. We were very close in the early years—in the early ‘50s—and we spent lots of time together. His notion was—who knows, maybe I was influenced by it; I don’t know. There was no technology for music at that time. His notion was to make art.

He was very well-read—extremely well-read—but he chose film because he felt that it was not only a new medium for the future but also that film stock itself wouldn’t live—it would die. And we used to have these talks—maybe we should just close libraries so people would just live now and make things now. Of course, we spent a lot of time in reference libraries in Denver, looking up books and things like that, so it was kind of immature. But it was that notion of wanting to do a new new thing.

When we were starting the Tape Center in the early ‘60s in San Francisco, Stan came and lived in San Francisco for maybe a year. He actually made a film of us, which we can’t find—nobody can find it now. But he was trying to create a new new. He didn’t like many of the experimental people at that time—well, there weren’t that many—but those people whom I knew.

Certainly, Stan didn’t think he was making new old things, new old art, by having people talk on film, because you had that already going on in the theater. It should be an art form of its own. That was the real feeling at that point in time. It never really materialized to a large extent, but that’s what he was trying to do.

I think it is very similar to what I’ve done—what you hear on records is pretty much new, and not some new old music. I think it’s extremely difficult to make a new new thing, and I think you can influence people. But then abstract painting lasted for a while. It had the same impact. It stays, but still, the majority of people don’t go in that direction. But it does have an impact. It does make a change. In that respect, we were similar.

PH: Morton, what a pleasure to talk to you. It’s really wonderful. Reading about that moment in 1959 when the credit card first came about, and those pivotal moments when things actually changed, I imagine that Marshall McLuhan would have, at some point in your life, had an impact on you.

Thinking about that, I was wondering, what better way to end than to ask you to comment on this Marshall McLuhan quotation, where he says, “Every society honors its live conformists and its dead troublemakers.”

MS: Yeah, well, a group of us actually read some notes from the lecture he gave that led into Understanding Media. So we knew McLuhan’s writing almost two years before the book came out—three years, maybe even—and it was a big influence on me. The quote I like is, “We walk into the future backwards, looking through a rearview mirror.”

PH: Yeah, it’s fantastic. How do you understand that, Morton?

MS: Well, I’ve understood it differently throughout my life, but now I understand—because I’ve been listening to audiobooks on how the brain works with memory—that we have no choice. I used to think we had a choice, but now I don’t think we have a choice.

We have to reconstruct the past. We have no future. The future is always now, and we only have the past and the present. We don’t have the future; we’re constantly moving into it. And so, the secret for me—and I think that’s what it’s come to mean—is that you have to reorganize the past and allow it to break through in new ways to make a little crack ahead.

You’ll see a footprint that happens to go forward, so just try to look forward, you know. I can tell you that if I drop something, I know it’s going to hit the ground. That’s about it. Other than that, you’re just guessing. So, it’s the idea of constantly opening this up and pushing that road ahead—gradually being able to turn your head from the rearview mirror and walk into that dark future, making little, tiny steps at a time. That’s been my life. That’s it.

PH: Morton, thank you so much. Thank you so much for taking my call. It’s really been a great pleasure to speak with you. I hope that someday, when travel again is possible, we can meet in person. But until then—

MS: Oh, that would be very nice. Can I give you one little thought—because this being whatever you call these programs, the being locked up, the quarantine. I’ve always wanted to be the first colonist, or among the first colonists, of the moon or Mars. In either case, I have a little picture on my wall of people with little things around their heads. They’re out in the field but have these things around their heads because there’s no oxygen in the air.

When this first happened, I thought, well, I can’t go to Mars and I can’t go to the moon, but if I did, this is the way I’d have to live: in my house with oxygen in it, and I’d have to talk to people through technology. So, I mean, it’s not that I’d like doing that, but it gave me a sense that if we did actually colonize, this is the way we’d have to live—in quarantine, at least for many generations.

So, I’m not talking about what a wonderful thing it would be, but for me personally, it’s sort of like I never got to go to the moon or to Mars. This gives me a sense of what it would have felt like and what it will feel like at some point.

PH: When we go.

MS: Yeah, when we go… okay, that’s it.

PH: Morton, thank you so much, and all the very best. Stay safe and let us hope we meet here, or on the moon.

MS: I would prefer Mars, actually, but the moon’s okay.

PH: Okay. It’s a date and it’s a deal.

MS: Okay.

PH: All the best.

MS: Okay, all the best to you too. Thank you. Bye-bye.

PH: Bye-bye.