Based in Thailand, the twelve members of the TEO ensemble give concerts almost every single day. Their music, performed on instruments including oversized drums, harmonicas, chimes, and the ranat (a Southeast Asian version of the xylophone), contains both composed and improvised sections and sounds, like a blend of local folk melodies and the music played in Buddhist temples.

All members have received a first-class education from Dave Soldier, a conceptual artist and guitarist who briefly performed in Bo Diddley’s band, collaborated with author Kurt Vonnegut, composed string arrangements for David Byrne, and worked with Pete Seeger (he is also a neuroscientist and professor working under his given name David Sulzer at Columbia University).

The TEO has recorded three albums so far and has been visited by journalists from renowned publications such as The Economist and The New York Times. The BBC has dedicated a detailed article to them, and various video documentaries of their work can be found online.

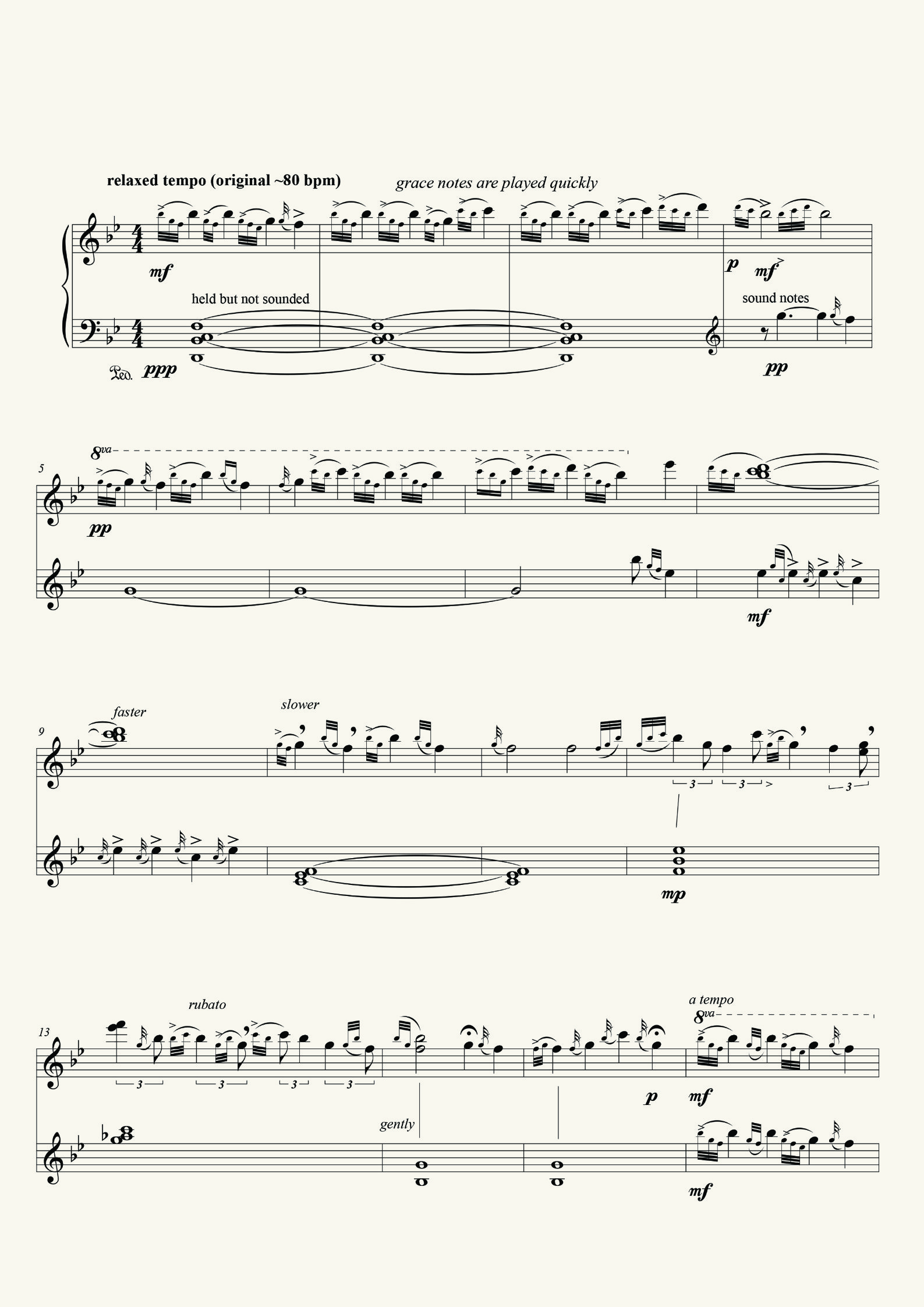

In 2012, The Composers Concordance Chamber Orchestra performed a transcribed arrangement of one of The TEO's improvisations at The DiMenna Center in New York. Following the performance, members of the audience were asked to guess who the composer of the piece might be. Impressed by the sounds they had heard, their responses ranged from John Cage and Charles Ives to romantic icon Antonín Dvořák.

This delightful anecdote still makes Soldier chuckle. The TEO, after all, consists entirely of Indian elephants from a conservation center near Lampang, a city in northern Thailand. Their triumphs seem to turn upside down a widely held belief about music — that it is the exclusive domain of humans, one of the few things that truly make us unique in this world.

However, even the Thai Elephant Orchestra hasn’t put the animal music debate to rest. Ever since the project went public, commentators have questioned whether their pieces can truly be categorized as genuine music. To Soldier, who went into the project almost without any expectations, that performance at The DiMenna Center was a Turing test of sorts.

“[W]hen asked if the sounds were or weren’t music, and if not informed of the identity of the performers, all questioned have replied, ‘Of course it’s music,’” he writes in a humorous and thought-provoking paper in Leonardo Music Journal.[1]

Soldier has even probed one of the orchestra’s members, Prathida, on her capacity to identify dissonance. Speaking as Davis Sulzer to The New York Times, he explained: “I put one bad note in the middle of her xylophone. She avoided playing that note until one day she started playing it and wouldn’t stop. Had she discovered dissonance and discovered that she liked it? She outsmarted the researchers.”[2]

Of course, the DiMenna Center performance wasn’t really a Turing test in the true meaning of the term. Turing’s Gedankenexperiment was devised to test the humanness of artificial intelligence: If a human subject is unable to distinguish between the responses of an AI and those of a human, the software passes the test. But animals are not artificial intelligence; a piece of music is different from a set of answers to specific questions; and training animals to play instruments is not the same as programming software.

Nonetheless, the outcome of Soldier’s experiment is remarkable. After all, the performances of the TEO are not strictly “animal music”. The elephants are not expressing themselves by blowing air through their trunks; they are working with human instruments to play human music. And rather than hitting random notes or coming up with alien structures, their pieces actually display a remarkable sensitivity — a sense of form, dynamics, and breadth that made shivers run down my spine the first time I heard them.

Had they been, as the skeptics would likely have it, just performing a circus routine? Or had they been, as the hopeful might suggest, emotionally transforming everyday experiences (like that one time someone snatched away the last banana right from under their trunks)?

For cellist, composer, and author David Teie, who conducted his own composition project with cotton-top tamarin monkeys (Saguinus oedipus), the conclusions are clear. “I tend to adopt simple and not specifically philosophical definitions,” he told me in email correspondence. “If it is produced like music and sounds like music, most people would agree that it is music, and if it is created on musical instruments, then I would say that is music.”

Certainly, all of the tracks on the albums of the TEO fulfill these criteria. Many of them are actually hauntingly beautiful. Then again, that was never the real point of contention. Almost everyone will agree that animals are capable of producing beautiful sounds — from the joyous trills of the wren and the wistful howling of wolves, to the mysterious clicks and cuts of marine mammals.

Some of these sounds have even been pressed on vinyl and released on CD to great commercial success. The seminal album Songs of the Humpback Whale, produced by biologist and environmentalist Roger Payne, for example, eventually went multi-platinum after its 1970 release. A selection of its songs would later be included on the Golden Record, which in 1977 was sent into space aboard the twin Voyager spacecraft as a message to other potential intelligent life in the universe.

But not everyone is as convinced as Teie that this automatically makes these songs music. Claiming that everything that sounds like music is music isn’t just circular; it also opens up an entirely new can of worms. Are those sounds that do not sound like human music, then, by default, non-music (or nachtmusik, as Soldier calls them)? What about the sounds that have similarities to our music but are the result of entirely different processes, such as the rhythmical stridulations of cicadas and crustaceans?

Some have proposed an elegant solution to these queries: that the definition of music lies in our own perception. Says Columbian sound artist David Vélez, “Trixi Alina wrote in the liner notes to my album El pájaro que escucha that what we hear on the outside is just a reflection of our inside. The music is entirely in our consciousness. Birds don’t know about music; they just communicate through behavior. But when we listen to their behavior, we turn it into something else. We make it music.”

I didn’t ask him whether these thoughts might have been influenced by the reception of John Cage’s “4'33", but it seems likely. Cage’s most famous piece, after all, focused attention on the noises of the audience, the subtle sounds of the pianist, the ambient hum of the concert hall — in short, everything we previously considered to lie outside of music.

By shifting our focus to these elements, the piece seems to say that they suddenly become interesting, perhaps even musical. (The approach was summed up by Cage’s statement: “Wherever we are, what we hear is mostly noise. When we ignore it, it disturbs us. When we listen to it, we find it fascinating.”)[3]

Vélez’s approach circumvents many of the issues raised by Teie’s minimalist definition because his focus is now on the recipient and no longer on the sender. But how do we know what messages animals are sending? And will an increased knowledge of the content of their songs truly lead us to a deeper understanding of them?

To provide us with the raw materials to answer these riddles, myriads of artists and scientists all around the world are venturing into the field, capturing the sounds of nature, and listening through endless hours of recordings in an attempt to decode the signals.

A World of Sound

One of the world’s major hubs for research on animal sound is the Macaulay Library. Located three-and-a-half miles from Cornell University’s stylistically colorful, hilly campus, and idyllically embedded in a rich, intensely green wetland of trees, bushes, shrubberies, and an oversized pond, the library is part of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s 90,000-square-foot Imogene Powers Johnson Center for Birds and Biodiversity, which also hosts the Adelson Library and a state-of-the-art visitor center.

Once you’ve crossed the wooden bridge connecting the island-like center to its surroundings, you’re literally inside a world of sound. Over the decades of its history, the Macaulay Library has amassed vast amounts of data — all of it meticulously arranged and tagged by a team of experts and students.

Even more impressive than the size of the archive is the speed at which it continues to grow. When I spoke to the Library Director, Mike Webster, in 2013, the count for audio files stood at 100,000 recordings of 10,000 species. Today, just five years later, more than three times that amount is available.

As Webster emphasized at the time, the volume of audio files in itself would be useless if it weren’t for the fact that the quality and scope of the data are constantly improving. The focus has shifted from isolated, signature sounds to detailed behavioral studies that monitor animals in their natural habitats over extended periods of time. This has allowed scientists to understand how individual, seemingly meaningless sounds are embedded in a complex web of influences and relationships. And the equipment is now more advanced, widely available, and boasts far longer recording times.

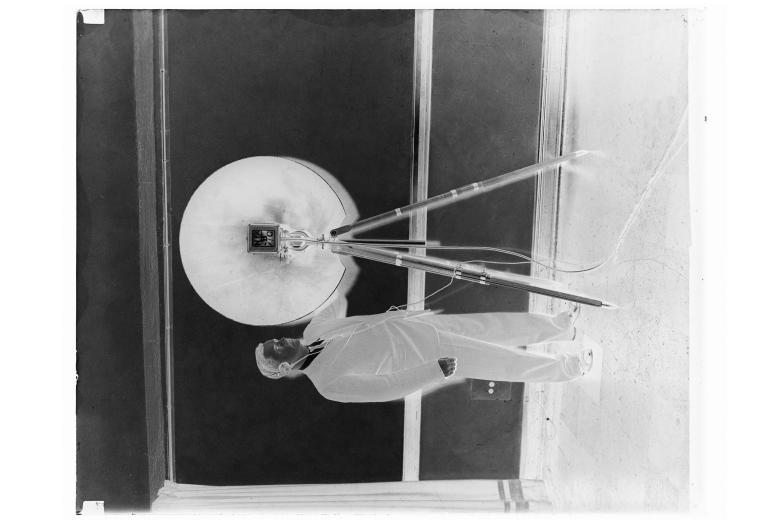

When bird specialist Ludwig Koch ventured into the wild in the 1930s, his gear weighed several kilos and produced a severely compromised sound. Today, as Webster stresses, one could “drop a recorder to the bottom of the ocean and collect it a year later to analyze an entire year’s worth of underwater sound”.

He is not speaking hypothetically. Norwegian sound artist Jana Winderen is already using 90-meter-long cables for her projects and says that she dreams of “wireless equipment to place hydrophones much, much deeper”.

Just like Winderen, her French colleague Rodolphe Alexis is a member of a passionate group of field recordists who are taking to the wild across the world to collect sounds that will either end up in the Macaulay Library or on their own releases.

For his project Sempervirent, Alexis spent two months in the forests of Costa Rica, one of the world’s biodiversity hotspots. The sheer amount of sound he brought back from the trip is breathtaking. A mere nine different species are included on the related 2012 Sempervirent album, released by the specialist label Gruenrekorder. But resting within his archive are recordings of sixty other animals, documenting a sound spectrum of an almost inconceivable richness and depth.

What makes Alexis’ approach particularly interesting is that he recorded panoramas of four different national parks as they changed over the course of several days. Sempervirent is a dynamic, living soundscape that includes everything from mysterious night-time chants to the ambient quiet of midday and the noises of lazy afternoons.

Most impressive, as Alexis recollects, was the break of day — the time when the dream-like state of darkness is pierced by the increasingly sonorous calls of awakening animals. Slowly it builds, with successive waves washing over the forest, leading to a majestic climax that can last up to half an hour. Then, as if prompted by an unspoken cue, the sounds recede; the noises calm down. One by one, the members of the chorus take their leave as the different animals go on with their daily routines.

The longer you stay in a place like this, Alexis says, the more you start to understand it. You begin to see structures where there appeared only chaos, and processes where there seemed to be randomness. As your nervous system familiarizes itself with the surrounding timbres and noises, it suddenly detects elements of a familiar palette: tones, frequencies, songs, and symphonies.

Does he believe this is, in a sense, the music of the forest, or the workings of the “great animal orchestra”, as musician and ecologist Bernie Krause once named it in the title of one of his books? Alexis is careful not to overstretch his interpretation: “Without wanting to sound too spiritual, I think that the apparent chaos of interwoven, natural noises requires some musicality, even if we’re not going to call it music.

"Some primitive, systemic harmony exists. It’s as if there were a logical arrangement, a language of nature, where each protagonist has to make itself heard in terms of harmonic placement, pace, and the number of songs. It seems that animals have an aesthetic conscience, a judgment. And I’m not just talking about communication. They can also be sensitive to a collection of objects that they find attractive.”

And yet, he is bothered by those who project aesthetic concepts onto the animal world: “What kind of aesthetics are we talking about? I think the concept is unique to contemporary art. If you ask me whether animals demonstrate some creativity, my answer would be ‘yes’, but if you ask me whether they produce art or culture, I would answer that I am not an ethology scientist nor a doctor in aesthetics.”

Interestingly enough, there can be no doubt in Alexis’ mind that the album Sempervirent is most definitely music because it involves selection, arrangement, and the careful diffusion of different voices across space. The act of composition creates a distance between the reality of the moment on location and its re-creation in the studio, creating a shift in the material. “It is a composed piece,” he insists.

A Creative Act

When Lara Cory and I set out to edit our book Animal Music (Strange Attractor, 2015), which was designed as an introduction to the topic, we deliberately left out the question of what constitutes music. It seemed like a sidetrack to us; the book was supposed to be a primer. And we did not want the content we had compiled to become overshadowed by a debate over semantics.

Looking back, that may have been an omission. Since then, I’ve become convinced that a precise definition of music wouldn’t just reveal a lot about our personal cultural backgrounds, but it would also tell us about the history of our species and our relationship with that history.

Such an approach wouldn’t only focus on the appearance of a sound but would take its origin and purpose, the intent behind it, into consideration as well. This is why the definition of music in Britannica (“an art concerned with combining vocal or instrumental sounds for beauty of form or emotional expression, usually according to cultural standards of rhythm, melody and, in most Western music, harmony”) doesn’t cut it.

Does instrumental sound include electronic synthesis and concrete, environmental noises (including animal songs)? Are beauty of form or emotional expression really the only reasons for making music? And what exactly are the “cultural standards” of rhythm, melody, and harmony?

In a bid to arrive at a more inclusive definition, Wikipedia describes music as an “art form and cultural activity whose medium is sound organized in time”. This far more modern perspective is abstract enough to include just about any contemporary form of music, but it ultimately remains vague.

Both definitions also seem to place too much emphasis on the organization of sound, whereas music, importantly, also deals with ideas, concepts, narratives, decisions, and direction. This is what Alexis meant when he made his entire rationale dependent on the question of composition, and it’s what Vélez was referring to when he placed the main focus on the listener.

It is not so much the nature of the sound that determines its musical quality; it is about how, why, and which kinds of sound are transmitted between a producer and her audience. If it weren’t, the entire debate around the musicality of animal sounds would have never been this difficult. Just like Alexis, most musicologists who do field work and have dealt with animal sounds for a long time will usually come to see the latter as the result of some sort of creative act.

Paul Pratley, the Honorary Secretary of the Wildlife Sound Recording Society, however, is one of the more pronounced skeptics. Considering how intensely emotional his first encounter with animal sound was, this comes as somewhat of a surprise.

“My very first experience of wildlife sound recording was when I was a teenager,” he recounts. “My father took me to the local bird group’s open day. There, for the first time, I was given the opportunity to listen to some recordings using headphones. The one that remains with me was of lapwings displaying. It felt like they were swooping and diving right through my head. I was hooked. From that day onwards I wanted to make recordings like that.”

The way Pratley tells the story brings to mind how children are often transformed by their first rock or pop concert. And although Pratley has since dedicated a large part of his life to the sounds of animals, he doesn’t believe they are music.

“Humans try to interpret the environment around them and turn it into music,” he explains. “Some species of bird, like the common blackbird, have a very melodic song, which can be translated closely to musical notation. But animals sing for a purpose because producing a sound takes energy and time. Therefore, an animal only produces a sound when it needs to — for example, to attract a mate, when alarmed, or to keep in contact with one another.”

Pratley’s objections are based on the assumption that there is always a utilitarian, functional reason for why animals sing, whereas music is about transformation, about going beyond what is biologically required. But this certainly hasn’t always been true for music over the course of its long and checkered history. At least, if we take Iain Morley’s The Prehistory of Music (Oxford University Press) as a reference point, we’ll arrive at a different conclusion.

Published in 2013, the book became an instant niche classic. It is remarkable in its multi-dimensional and cross-disciplinary approach, running the gamut from archaeology and neurology to creativity and craftsmanship. Most remarkable, perhaps, is Morley’s honest admission that what we don’t know might well exceed what we do. For every fossil or artifact we discover, Morley argues, there are most likely many, many more that have yet to be found, may never be found, or have long since decomposed.

Once we start taking these limitations into consideration, our seemingly clear picture of where and how music began turns into a puzzle with as many holes as pieces — which is not to say that we haven’t made significant progress. From the evidence he has gathered, Morley draws at least one undeniable and seminal insight: “Abilities that underlie some of our musical traits seem to be showing up in animals more and more.”[4]

And indeed, the vocalizations of many monkey species can sound remarkably similar to words, and some gibbons have been known to possess a liking for duets. These so-called “para-musical” forms of behavior exist in many different species, suggesting that when humans first started singing, a framework from which to draw inspiration was already in place: the wide spectrum of animal sounds.

Musicologist and semiotician Dario Martinelli, known for his treatise on zoomusicology, Of Birds, Whales and Other Musicians, even believes that “sound manifestations in non-human animals are homologous to musical manifestations in humans. They are not simply analogous.”[5]

Although our common ancestors might not yet have been capable of singing (or even producing particularly expressive sounds), they would have had access to the rudimentary processes from which these capacities would eventually develop. If Martinelli and Morley are right, our musical history is not just similar to that of animals; it would be unthinkable without it.

Read The Pleasure Principle: Part 2. Or move to Part 3.

Footnotes:

[1] Soldier, Dave, “Eine Kleine Naughtmusik: How Nefarious Nonartists Cleverly Imitate Music”, Leonardo Music Journal, vol.12, pp.53–48, 2002.

[2] Scigliano, Eric,“Think Tank; A Band With a Lot More to Offer Than Talented Trumpeters”, The New York Times, National Edition, p. B00013, December 16, 2000.

[3] Cage, John,“The Future of Music, Credo”(1937); Silence: Lectures and Writings. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press,1961.

[4] Barras, Colin, “Did early humans, or even animals, invent music?”, BBC – Earth, September 7, 2014.

[5] Martinelli, Dario, “How Musical is a Whale?”, Acta Semiotica Fennica XIII: Approaches to Musical Semiotics 3, 2002.