In his unceasingly referenced 1960 essay “Modernist Painting”, Clement Greenberg advanced his theory of “medium specificity” by focussing on the absolute flatness of painting. Two-dimensionality, according to Greenberg, is what makes painting distinct from every other medium. He claims in the text that the “making of pictures means, among other things, the deliberate creating or choosing of a flat surface, and the deliberate circumscribing and limiting of it.” [1] And he cites Kant as a reference for this interpretation: “Kant used logic to establish the limits of logic, and while he withdrew much from its old jurisdiction, logic was left all the more secure in what there remained to it.” [2]

Related to the logic of the Enlightenment in this way, painting, as picture-making, becomes a tautological exercise in which anything that extends beyond the conceptual limits one has deliberately circumscribed can, and ultimately should, be disregarded. It’s not surprising that it was largely on the basis of this flatness that Greenberg championed America’s ascendance in the modern art world. The ‘New World’ was meant to be a similar sort of picture; its mapped territory was an analogously circumscribed surface on which the white, masculine mind could work to create an internally coherent masterpiece of civilization. America was conceived as the ultimate blank canvas; it needed only to be primed through truly psychopathic violence.

Anthropologist Anna Tsing’s 2015 book, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins, describes how colonized land was transformed into surfaces that would support modern capitalist civilization:

In their sixteenth- and seventeenth-century sugarcane plantations in Brazil, for example, Portuguese planters stumbled on a formula for smooth expansion. They crafted self-contained, interchangeable project elements, as follows: exterminate local people and plants; prepare now-empty, unclaimed land; and bring in exotic and isolated labor and crops for production. This landscape model of scalability became an inspiration for later industrialization and modernization. [3]

Tsing’s analysis of mushrooms at times aligns with Greenberg’s analysis of painting in observations around ideals of self-containment; it counters such notions by describing the not only illusory but destructive nature of these ideals.

The mushroom she writes about is matsutake, a much-loved delicacy that grows throughout the world but almost exclusively in areas that humans have deforested. In Oregon, matsutake is foraged by numerous cultural communities of pickers who harvest it with varying degrees of legality. It is then distributed by multiple buyers and sellers in order to end up, most often, as an esteemed gift in Japan. Tsing traces the long and complex international supply and life chains of matsutake as they weave and tangle in and out of capitalism.

Every point along these chains — from how matsutake biology is enmeshed with that of pine trees and nematodes, to the often financially volatile negotiations between pickers and buyers — constitutes an encounter, a concept central to her analysis. “Encounters are, by their nature, indeterminate; we are unpredictably transformed.” [4] Western capitalism though, she emphasizes, has cultivated a steadfast refusal of transformation of this kind.

Self-contained individuals are not transformed by encounter. Maximizing their interests, they use encounters — but remain unchanged in them... A “standard” individual can stand in for all as a unit of analysis. It becomes possible to organize knowledge through logic alone. [5]

Comparing paintings and mushrooms might still seem a stretch, but Greenberg’s text is itself based on insights into both art and science. “That visual art should confine itself exclusively to what is given in visual experience”, he observes, “and make no reference to anything given in any other order of experience, is a notion whose only justification lies in scientific consistency...” [6]

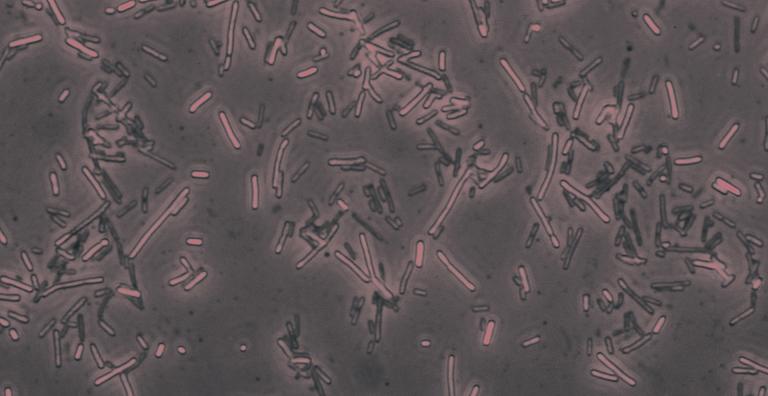

Tsing views this consistency more dubiously. She identifies scientific methods as “machinic”, a set of procedures in which a “phalanx of teachers, technicians, and peer reviewers stands ready to chop off excess parts and to hammer those that remain into their proper places”.7 Regarding biology, specifically, she states: “Species reproduction is [seen as] self-contained, self-organized, and removed from history... Self-replicating things are models of the kind of nature that technical prowess can control: they are modern things.”8 And again, she demonstrates that this bid for control based on standardized, scalable units wilfully disregards the fundamentally transformative nature of encounters that occur between species: “Even we proudly independent humans are unable to digest our food without helpful bacteria, first gained as we slide out of the birth canal.” [9]

Greenberg, for his part, states that he didn’t think the artists he wrote about were actually consciously trying to achieve the purity of modern scientific methods in their paintings. Nor, as he states when correcting some unnamed respondents in the 1978 postscript to his essay, did he himself hold the view that a painting’s purity was directly correlated it to its success. He positions himself merely as an observer of modern behaviour:

From the point of view of art in itself, its convergence with science happens to be a mere accident, and neither art nor science really gives or assures the other of anything more than it ever did. What their convergence does show, however, is the profound degree to which Modernist art belongs to the same specific cultural tendency as modern science, and this is of the highest significance as a historical fact. [10]

Tsing and Greenberg are not using the term “modern” in precisely the same way, and Greenberg’s interpretations of medium-specificity did not of course become a long-term explicit norm for either the production or analysis of art (see: post-modernism). But in considering ‘cultural tendencies’ (which are not themselves the stuff of scientific consistency), it’s not difficult to find instances of self-containment throughout the contemporary art world. The ‘white cube’ is essentially a scalable, self-contained unit that is reiterated around the world; gallery walls effect an erasure of local environments. Materials are often reduced to surfaces — even as illusionism has been disparaged in favour of clear-eyed recognition of paint-as-paint, critical analysis has generally made little, if any, acknowledgement of the chemistry, labour requirements, supply chains, or environmental impacts of this paint.

With respect to these two points alone it could seem as if the primary responsibility owed to an artwork is to prepare an empty space for it, a space in which people can stare intensely at its surfaces and think about how best to situate those surfaces within the self-contained cannon of Western art history. And art has actively been used to further the isolating tendencies that facilitate capitalism. In an essay for their 2014 SITE Santa Fe exhibition Unsettled Landscapes, curators Candice Hopkins and Lucía Sanromán discuss how the landscape genre has been used as an alibi to “cover up a culturally specific way of seeing”.

The Othering of the land and those directly associated with it — including Indigenous workers, indentured farm workers, and other agricultural labourers — is fundamental to this process [of using landscape as alibi]. The Western worldview creates a type of selfhood that is primarily invested in the desubjectification of experience in order to facilitate the management of (seemingly) inert, passive bodies that support the processes of production and consumption prevalent in late capitalism. With this in mind, our question is not what is landscape, but rather how is landscape used to support particular social values. [11]

Art forms have also been subjected to these isolating processes. We know European artists leading up to the era of Greenberg’s critical dominance drew from wherever they wanted, they Columbused abstractions, for example, from the artistic practices of cultures around the world, claiming geometric aspects of other people’s work as their own artistic ‘discoveries’, either severing these forms from their cultural and material contexts, or relegating these contexts to an idealized, traditional and therefore naive past. Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg scholar and writer Leanne Betasamosake Simpson (Alderville First Nation) describes the colonial abuses of land and culture: “The act of extraction removes all of the relationships that give whatever is being extracted meaning… extracting is stealing — it is taking without consent, without thought, care or even knowledge of the impacts that extraction has on the other living things in that environment.” [12]

In trying to either ignore or maintain control over the unpredictable transformations that encounters produce, the danger is perpetuating destructive selective extractions rather than generative, complex relations. Simpson also writes: “The alternative to extractivism is deep reciprocity. It’s respect, it’s relationship, it’s responsibility.” Limits are intrinsic to relationships. They mark, among other things, where individual experience and comprehension ends, but that does not have to be the point at which to circumscribe and sever. A recognition of limits can constitute a respectful acknowledgement of the presence and value of that which can’t be accessed or understood, and can prompt an appreciation of how deeply entwined we are with what is often unknown. In addressing artworks, criticism too can be a recognized as an unpredictable encounter in which authority is balanced with humility. It can be approached as a submission to — a commitment to — the process of transformation.