On March 18, 2013, the BBC reported that the European-owned plane maker Airbus had won a record order for 234 planes worth EUR 18.4 billion from the Indonesian air company Lion Air. The order trumps last year’s record order of 230 Boeing planes — also from Lion Air. This fact confirms the current state of Indonesia, a country that is definitely “flying high”. Considering the reality in which we live, a reality that is ever more porous, where every facet — culture, and finance above all — is intertwined and deeply connected, the fact that the art scene in Indonesia is also flying higher than ever comes as no surprise. Before presenting the practice of a selected group of artists working in Indonesia, a brief analysis of the scene and its recent emancipation might be required.

In May 1998, the Indonesian dictator General Mohammed Suharto was forced out of power when his cabinet and the other generals — faced with escalating mass protests — abandoned him. The second upsurge of protest, drawing in even larger layers of the population in November 1998, forced Suharto’s successor as Indonesian president, Bacharuddin Jusuf Habibie, to call elections. Around the same time — between 1997 and 1999 — the curators Hans Ulrich Obrist and Hou Hanru organized the traveling exhibition “Cities on the Move”. The exhibition —focused on the new model of metropolis developed in Asia — included among the others Arahmaiani Feisal — whose work we will discuss later — Heri Dono and the Dutch-Indonesian Fiona Tan.

While Heri Dono is still active and can be considered the pioneer of the scene, in the following decade, the 2000s, the situation evolved, and ‘traces’ of Indonesia started to appear in the work of international artists: from Damien Hirst’s series of paintings developed while staying in Bali to Luigi Ontani’s use of the local Balinese craftsmanship for his masks, Indonesian culture — one of the richest and multi-layered in the world — has become more and more present in the contemporary art field and people started to refer to Indonesia not only as a tourist spot but mainly as a place for cultural production.[1]

A pivotal figure in this regard is the American artist Ashley Bickerton who — after his breakthrough in the 1980s New York art scene as part of the Neo-Geo group, together with Jeff Koons and Peter Halley — moved to Bali and started to make disturbing works that took his interest in the legacy of painting to the next level, merging it with an ironic and rather direct critique of the way Westerners look at tourism and exoticism in South East Asia.[2]

While this was happening, a group of Indonesian artists realized that their work needed to circulate outside the country. They started to understand the need for showing abroad and having connections with a broader community. If this seems pretty obvious for any scene coming from the so-called periphery — if this word still makes any sense—and we can see it in the development of the art scenes in Poland, Mexico, Romania, and Israel, for Indonesia, things were very different. The swift pace of the economy in the country generated a unique situation: a group of businessmen, mostly Chinese Indonesians, who are also avid collectors of contemporary art, gave financial stability to many artists who therefore needed time to realize they had to step out of their comfort zone and face the international arena.

This process took a long time also due to the lack of infrastructure, or rather the presence of another kind of (infra-) structure, where the artist leads his own market — here to be understood not strictly financially — in tandem with the collector and often with the auction house, leaving gallery owners, curators and art critics marginalized.

At the same time, the porosity of our reality, a quality that is even more visible in the field of visual art, allowed artists to move forward through grassroots action and self-organization, although some examples, like Cemeti Art House in Yogyakarta, remain quite provincial in their way of dealing with the art system, not understanding that the borders between what is institutional and what is commercial, between the underground and the establishment are continually being negotiated and redefined. In this scenario, examples like the 2013 Indonesian Pavilion at Art Stage Singapore and the Indonesian Pavilion at the 2013 Venice Biennale[3] become relevant moments of exploration and understanding of the emerging art scene in the country.

A participant of both the aforementioned projects, Entang Wiharso (Tegal, Central Java, Indonesia, 1967) is definitely the leader of the newly emancipated scene in Indonesia. Working with different media, his work consists of sculptures, installations, paintings, videos, and performances. They employ a strong visual language to create a link between elements of the Javanese culture — such as the puppet tradition — and biographical elements, as in the lightbox The Family Portrait (2012), which can be considered the manifesto of what he calls “the Indonesian Diaspora”.[4] In his work, the figure of the artist, Wiharso himself, in many ways is presented as an outcast. The artist symbolically presents this relationship to the world and its related state of mind through the quasi-mythological figure of the “black goat”, which is a recurring element of his practice. At the same time, confirming the necessity of being active “in the field” and not only in the studio, Wiharso — who is based between Yogyakarta (Jogja) and Rhode Island — has been able to pair his art practice with interesting side projects like the 2003 Jogja Biennale, whose structure he reshaped with Christine Cocca, as well as Antena Projects, a project-based initiative he runs, again with Cocca.

Also included in both the pavilions in Singapore and Venice is the work of Sri Astari (Jakarta, 1953). An important figure of the Indonesian art scene, Astari is the embodiment of many complexes and fragile contradictions: from being a woman artist in the biggest Muslim country on the earth to her desire to link her Javanese roots — which she shares with Wiharso — to the recent developments in Indonesian consumer society. Perfectly illustrating this “state in-between” are the installations she presented at the 2010 and 2012 editions of Art Jog in Yogyakarta. The Peace Keeper (2010)[5] is a fabric sculpture consisting of a woman’s purse whose outside surface is pink-instead-of-army-green camouflage. The inside surface is a pattern featuring Rupiah’s bills — a sign of the money-oriented attitude of the Indonesian army. Guarding the purse is a small figurine whose features are reminiscent of Punakawan, the Javanese theater's ironical and critical servant character.[6] In Skeleton Woman and the Dragon (2012), a skeleton dressed in traditional female Javanese clothes — through which you can see a light-flashing plastic heart — looks at the audience with frightening eyeballs while guarding her ‘pet’: a life-size cherry-red plastic reproduction of a Komodo dragon. In many ways, Sri Astari is the quintessential representation of the female dandy — an oxymoron in itself, even more so if we consider the Indonesian context.

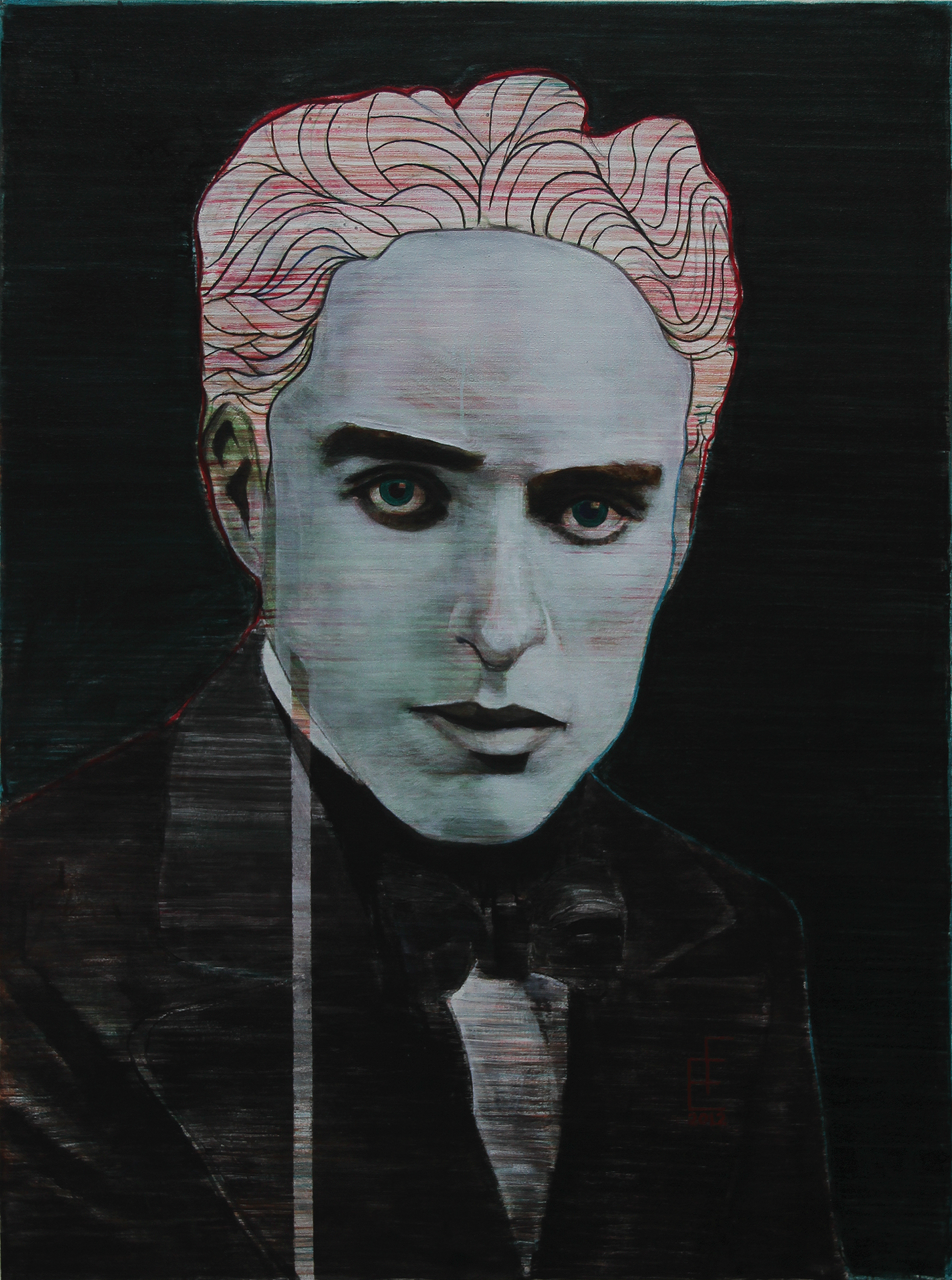

Balancing the studio practice with a more systematic and structurally engaged attitude is Fendry Ekel (Jakarta, 1971). Born to Indonesian parents and raised in the Netherlands, which colonized the country for 350 years, he studied under Michelangelo Pistoletto, Narcisse Tordoir, and Luc Tuymans, who inspired and influenced his approach to painting, an approach Ekel always pairs with a mix of different cultural and historical references he consequently twists: from Franz Kafka under the Empire State Building[7] to Walter Gropius dressed like a military figure, from Leon Trotsky with the hairstyle of the already appropriated[8] poster of Bob Dylan designed by Milton Glaser, to Mata Hari, the legendary Dutch exotic dancer — born Margaretha Geertruida Zelle — who was accused of being a double spy and eventually executed by a firing squad in France under charges of espionage for Germany during World War I. A real “painter painter”, Ekel is also the co-founder of OFCA — Office for Contemporary Art International, which originally started in Amsterdam. Now based in Yogyakarta and co-directed with Astrid Honold, this artist initiative continues its unique activity, creating dialogues among fellow artists, sharing knowledge, organizing lectures, and producing exhibitions and books in collaboration with curators, galleries, and museums.

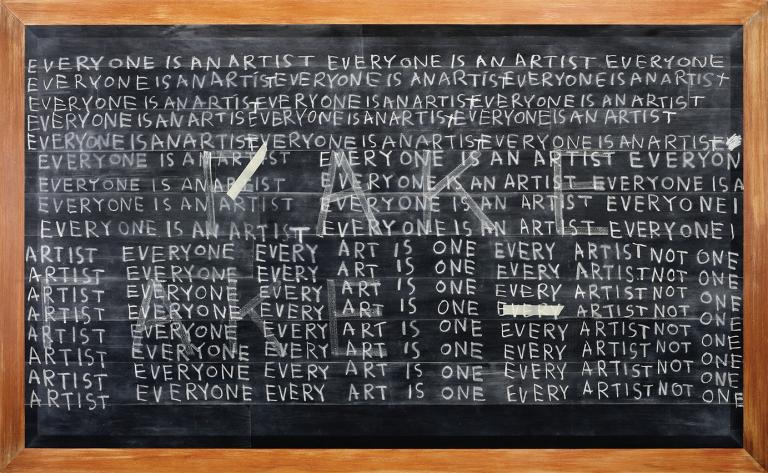

A member of OFCA and a real “painter painter” is also Jumaldi Alfi (Lintau, West Sumatra, 1973), whose leadership level within the Indonesian art community is similar to that of Wiharso. However, in the case of Alfi, leadership is always delivered through collective and collegial efforts rather than through individuality and isolation. In fact, before OFCA, Alfi was a member of the Jendela Art Group together with Rudi Mantofani, Yusra Martunus, Yunizar, and Handiwirman Saputra. The group can be seen as one of the most interesting models of semi-collectivity in Asia. It can be easily compared to the Ładnie Group in Poland, hobbypopMUSEUM in Germany, and Rafani in the Czech Republic.[9] Among the most celebrated artists in Indonesia, Alfi’s best-known body of work is the “Blackboard Series”, a group of large-scale Trompe-l’œil canvases which “repudiate the superiority of Western thoughts and norms and present an alternative, edited visual thesis” and “often reflect futile efforts by Indonesian artists to come to terms with expectations about contemporary art practices that please specific aesthetic or thematic preferences”.[10]

Like Ekel, the practice of Melati Suryodarmo (Surakarta, 1969) came into shape through the dialogue between the East and the West. Based in Gross Gleidingen, Germany, and Surakarta (Solo), Indonesia, the artist studied with Marina Abramović in Braunschweig and aligned with her teacher's durational and body-based actions. Syryodarmo became one of the most interesting art performers of her generation. Always based on the artist’s physical strength, her pieces use the gallery’s architectural elements questioning the pristine and aseptic state of the so-called white cube with theatrical and sometimes dangerous performances: from her one-hour performance at Art Stage’s Indonesian Pavilion, where she used clothing to investigate concepts of migration, identity, and behavior, to her performance at the National Gallery in Jakarta where she blocked the door connecting two rooms of the museum with a brick wall which she then destroyed by walking through it. For Exergie — butter dance (2000), her infamous[11] performance at Lilith Performance Studio in Malmö, Sweden, she wore a tiny and tight black dress and high heels, dancing on a block of butter, to the rhythm of music from Makassar, South Sulawesi, Indonesia, and falling on the floor several times.

Also performative, although not exclusively so, and definitely politically and socially engaged, the life and work of Arahmaiani (Bandung, 1961) question the very core of the “Indonesian identity”, a dynamic notion that can hardly fit the monolithic standards of the West. For instance, her untiring movements across the globe — from Australia to Tibet, from Europe to the United States — and related projects can be considered a macro projection of the movements within Indonesia itself, an archipelago of 18,307 islands and one of the most populated countries in the world.[12] Furthermore, her personal story — her father is an Islamic scholar, and her mother is a Javanese of Hindu-Buddhist extraction — mirrors the variety of cultures, races, and religions cohabiting within the same nation. Perfectly summarizing her “attitude” are two projects recently presented in Yogyakarta and Singapore. Stitching the Wound (2011), her participation in the 2012 Jogja Biennale consisted of an installation where Arabic signs were transformed into large sculptures made of stuffed fabric that the artist consequently displayed on the floor as well as suspended in space. At first sight, feminine, the work can be considered catharsis from her paternal roots. On the other hand, Memory of Nature (2013), her performance and installation at Art Stage Singapore, which was destroyed on the last day of the fair, was focused on environmentalism, and included among other things, a panel discussion with a llama, an environmental activist, and an earth scientist.