It may be a clichéd expression, but none of us is able to choose the time and place in which we were born. When asked where we are from, some may reply based on an inherent relationship to where they were born and raised. But these days, we are also free to choose our answer according to other criteria. Some may have a transient connection to place but nevertheless feel this connection to be an important one. With such experiences playing out in different parts of the world, we find ourselves in greater need to imagine other lands and the people living there. The works of writers such as John Maxwell Coetzee, Sijong Kim, and Michiko Ishimure offer a fortunate opportunity for us to broaden our imaginations in such a way. I feel similarly fortunate in being able to view the work of Chikako Yamashiro.

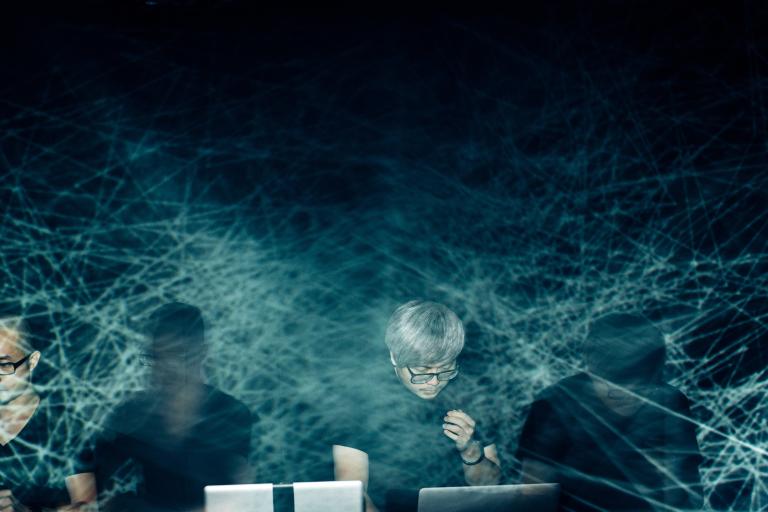

Yamashiro’s video works contain very little that could be considered descriptive; they are closer to poetry than prose. This allows her viewers to surrender themselves to the flow of images readily. Her works are remarkable for how the images seem to drift in a continuous experience without offering any fixed meaning. Lulled in such a way, viewers may be caught off guard by frequent, sudden changes in pace, and so this characteristic quality of the work may be seen to act in a way that is more subconscious than explicit. In other words, one is enticed to view the works through the senses rather than through the intellect.

Also noteworthy is how this allows Yamashiro to avoid positioning the political issues that have been confronted by many artists from Okinawa — the prefecture in which the artist was born and raised — in between the viewer and the work as existing knowledge. As one might expect, Yamashiro’s work gives considerable weight to Okinawan political issues. But as the work does not offer explanations, viewers may overlook such implications. Even so, the experience of having viewed the work should stimulate the audience to take a good look at similarly structured problems in other parts of the world. Therefore, it is highly appealing that the images, which flow like water at varying tempos, have a sense of plurality, the result of places other than Okinawa being folded into them. Let us take a closer look at some of the works in question.

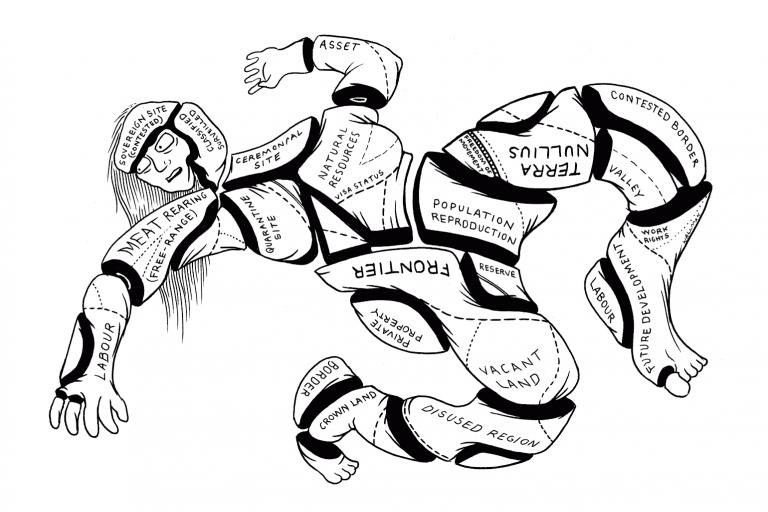

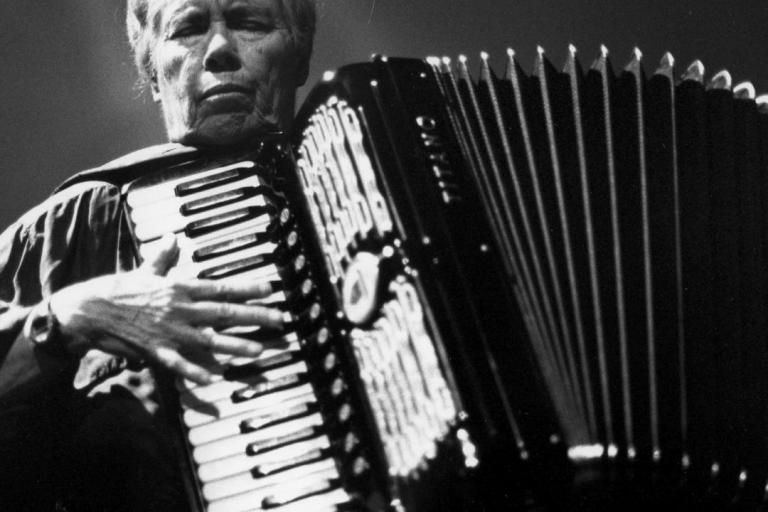

The first work I would like to discuss, “A Woman of the Butcher Shop” (2012), can be described as a video installation that explores the desire for flesh. It depicts a street market selling goods, including US military surplus and agricultural products. A large group of male workers wanting to buy food crowds around a woman running a meat stall. Their desire is exposed as more or less like that of an animal. Many viewers are likely to perceive the implications of violence against women in this image of men who work in construction around Okinawa’s US military bases, where sexual violence continues from the war years into the post-war period. In 1995, 85,000 people gathered in a mass rally to protest the assault of a 12-year-old girl by US marines. Of course, this problem is by no means limited to Okinawa; it concerns the history of war and humankind. During the early 1990s, former comfort women of the Imperial Japanese military forces gave testimony, with the Japanese government then acknowledging its involvement. Yamashiro’s representation of areas around US military bases intimates war and sexual violence.

Meanwhile, the butcher woman in Yamashiro’s video holds a large chunk of meat in her hands. She ecstatically smells it in a gesture where the desire for meat transcends gender differences. If anything, meat appears to be treated as a metaphor for the circulation of different things, rather like the practice of cultural cannibalism espoused by José Oswald de Souza Andrade, in which the other is taken into oneself. In bringing to our awareness such cycles of destruction and creation — in which a living creature is killed, becomes meat, and enters into the body of another living creature — the viewer is given the impression that the complex mechanism of political/economic dependence surrounding the history of military bases and war is absorbed into a larger cycle of culture and nature.

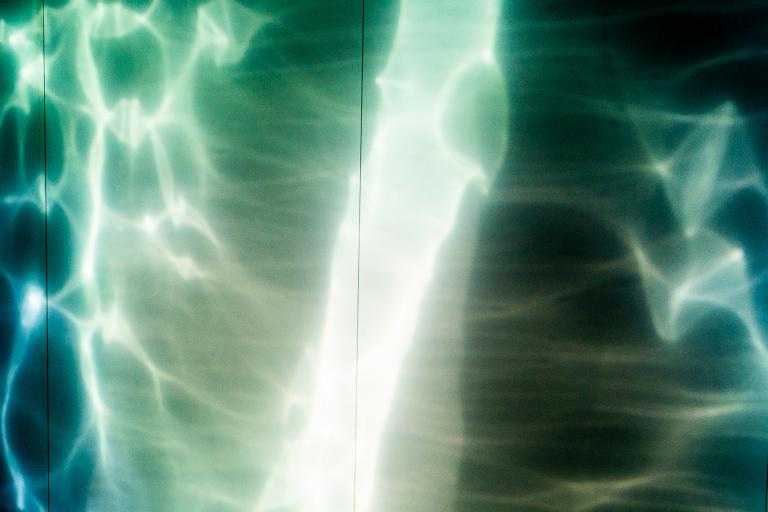

With meat creating such a powerful image, recalling the underwater shots that appear at both the start and end of this video may prove difficult. Shots of women walking in limestone caves like those commonly found in Okinawa are also incorporated into the work. All these contribute to a feeling of layering the body and nature, making the viewer imagine the workings of a primitive spirit or a kind of animism.

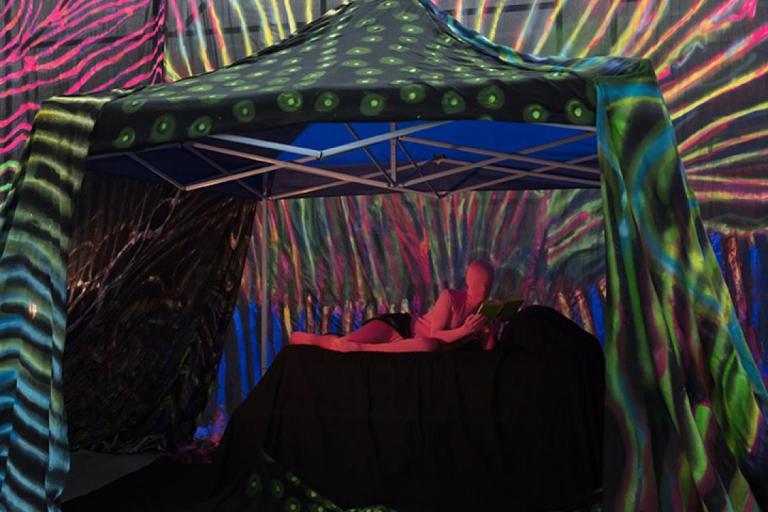

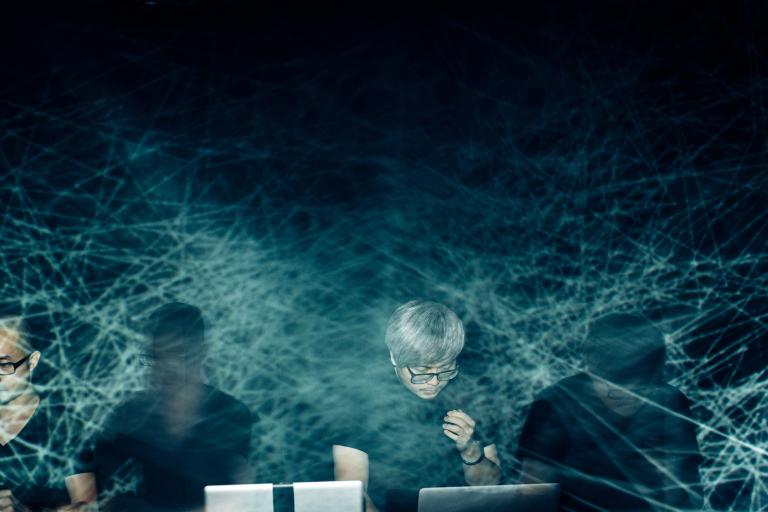

Next, let us move on to “Mud Man” (2016), a video installation in which the sound component and images of groups of people are used to create impressive variations in pace. Covered in mud, people lie on the ground, looking both as if they are dead and in the act of protest. Clumps of mud resembling bird droppings fall from the sky, waking up the sleeping people. They get up and start listening to words that emanate from within them. From the handouts accompanying the artwork, one can infer that these words are those of Japanese and Korean poets, but the viewer cannot take in the meaning of the words, as the video is not subtitled. Rather, one is left with an impression of words that flow out of the mud as a kind of melodic sound.

Next comes a battle scene, its uplifting mood created by the light emanating from fireworks and the vocal percussion of beatboxing. A collage-like way of working with images follows, in which scenes of people crawling forward are superimposed over those of people dancing in clubs. Images of the Battle of Okinawa and the Vietnam War also appear. Video clearly shot from a US military perspective and hip-hop music provide a rich feel for the cultural hybridity of post-war Japan and seem to indicate the ease with which the human body and technology can be redirected to combat.

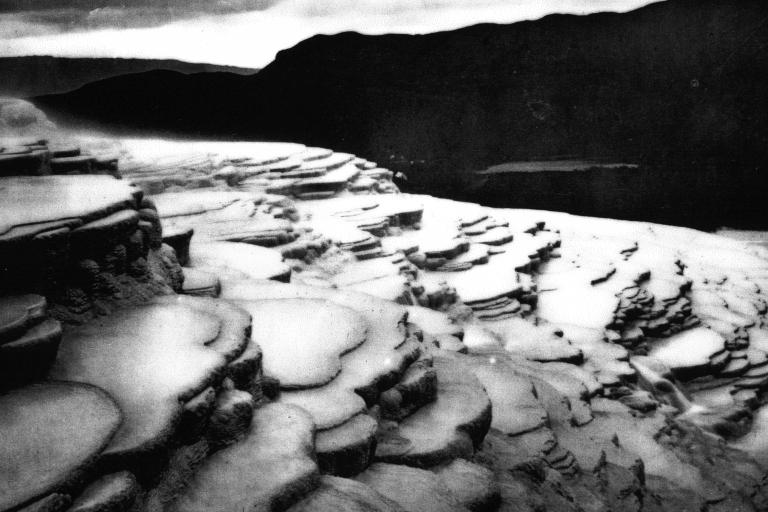

Scenes from Okinawa, such as its limestone caves, military bases, and the construction sites of Henoko (where land reclamation work is underway to build a new US military base), repeatedly appear in the work. Meanwhile, images from Jeju Island, South Korea, are also mixed into bird’s eye views of fields and hills. The work is edited to make no clear distinction between Jeju and Okinawa. Between the two islands, which are located far from the center of their respective nations, lie histories of violence and voices of resistance.

The words of the poems that flow out of the clumps of mud at the video's opening are experienced as sounds, and it is particularly impressive how this continues, like an echo, right through to the end of the work. We live in a world in which the voices of the past continue to drift in the air. Most certainly, these words are floating around even when we are not viewing the work; it is just that we are not listening.

In contrast to the past, contemporary society lives at a distance from the dead. In “Mud Man”, I feel that the voices of the dead echo here and there in the shots of Okinawa and Jeju Island. This can also be felt strongly in the rather powerful scene at the close of the film depicting the rhythmic clapping of hands, followed by a multitude of limbs stretched upward from a vast field of white lilies. The hands that the many men in “A Woman of the Butcher Shop” stretch toward us are now being stretched upward. Who are these people, whose faces we cannot see, who stretch their hands solely toward the heavens? They look like plants with hands sprouting up from the soil.

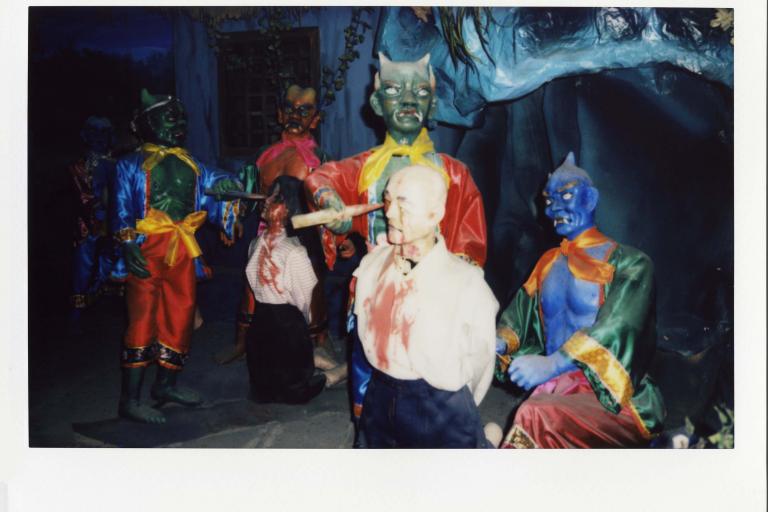

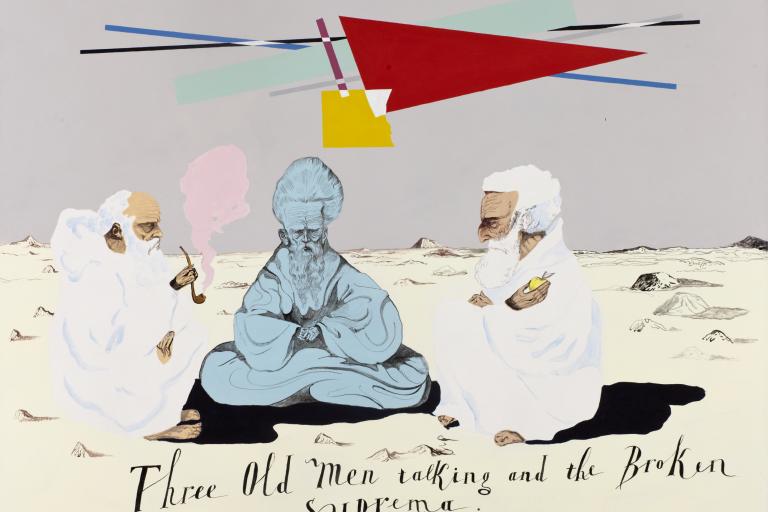

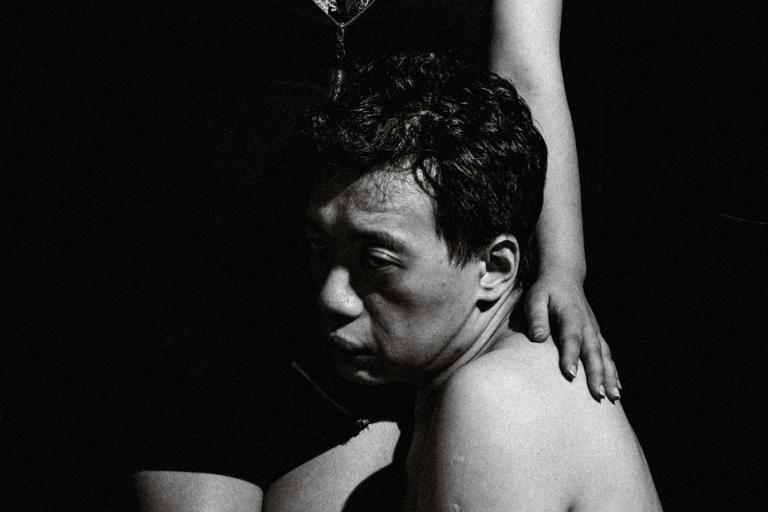

The final work I wish to discuss is “Chinbin Western: Representation of the Family” (2019). Chinbin is an Okinawan sweet, a bit like a crepe. In the manner that the Westerns made in Italy were called ‘Spaghetti Westerns’, this film (which is an opera) was made in Okinawa, hence, “Chinbin Western”. The story unfolds in a dry quarry, a landscape reminiscent of those found in that genre. A man (the husband in one of the two families around which the film revolves) works in the quarry, which mines material for land reclamation in Henoko, where the new US military base is to be built. He makes a show of supporting his seemingly happy family. Despite the children’s anxiety about the discord between their parents, the family manages to maintain its happy-looking veneer. Conversations between family members are sung in the imported culture of opera. This seems to imply that the male-centered ideology that maintains an image of the family for outward appearances is complicit in building the base.

Meanwhile, the film goes on to show the family of a different woman with impressive tattoos and piercings. Her conversations with her grandfather suggest a way of life that tries to be intimate with the history of nature and the land. At the quarry, people dressed in clothing from the time of the Ryukyu Kingdom (1429–1879) perform a play. “Chinbin Western” can be described as a mélange of traditional and imported culture, representations of the contemporary family, and heterogeneous elements.

A feature common to all the works discussed is how the video, which flows in a water-like way at different speeds, can dismantle a dominant story whose existence was once unshakeable through a technique of ‘crossing over’ different content. For example, in “A Woman of the Butcher Shop”, the cycle of destruction and creation that humankind has repeated many times over is superimposed onto the relationship between war and sexual violence. This does not obscure the general idea of the problem. Rather it gives a sense of the deep-rootedness of human desire. In “Mud Man”, war and words concern more than one place. The video’s cultural process of transforming a history of violence into verbal memory and an act of healing is impressive. Meanwhile, “Chinbin Western” dismantles the family's narrative through the contrasting intrusions of tradition and modernity.

Yamashiro’s work is also greatly appealing for how it dismantles dominant narratives and seems to shift them into other cycles. This may be due to the artist’s viewpoint on nature, such as the water or the caves in her work. How human beings in these videos are enveloped in such natural elements and seemingly become one with them is also striking. Political problems that one would have thought to be unique to Okinawa flow out into the cycle of nature. They transcend local issues to form a continuum between Okinawa and other parts of the world.

What I would consider important here is not that such problems will disappear by being integrated into the existence of Mother Nature. Rather, when seen as an extension of unstable human desire and spirit, these problems allow us to feel the close connection between the individual and external society. While having access to a huge amount of information, the individual is also under the firm control of politics and capital. I would argue that an imagination that allows the individual to associate with the external world is needed to expand the depth of our lives and overcome the instability of human desire.

Thanks to Natalia Filimonova and ZETTAI for their collaboration in producing this article.