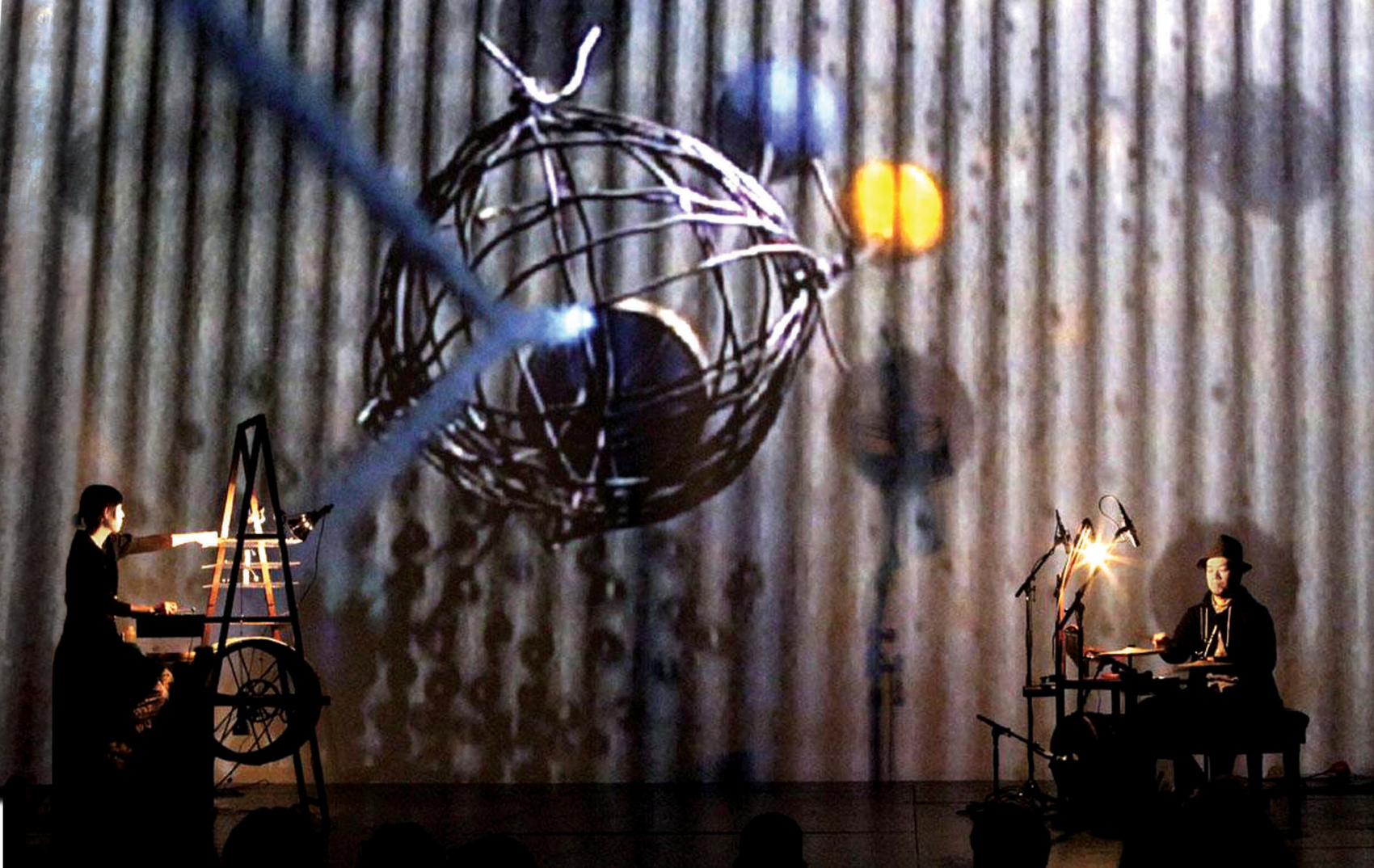

Japanese duo Usaginingen perform with a pair of large-scale, hand-built instrument-machines named “TA-CO” and “SHIBAKI”. ‘Usaginingen’ translates literally to ‘rabbit-human’, a hybrid concept reflecting their intuitive ability to dwell simultaneously and extremely effectively in multiple territories: cinema and music; analog and digital; screen and stage; craft and electronics.

Emi and Shinichi Hirai developed the project in Berlin after moving there in 2010 from Tokyo, where they had been working — perhaps surprisingly, given the rapid success of their venture into the arts — as an advertising graphic designer and a radiologist, respectively. They have since performed in over 40 cities in 15 countries, recently making their North American debut as part of the Antimatter Media Art Festival on the West Coast of Canada. The duo has been enthusiastically received at numerous European festivals; their performance at the 2014 Reykjavik Visual Music — Punto y Raya Festival won the award in the category of Live Cinema.

Watching Usaginingen play their machines is mesmerizing in and of itself, but their physical interactions with TA-CO and SHIBAKI are just one element of a deeply immersive experience that fluidly synergizes projections, shadows, reflections, live percussion, and Ableton-structured electronic music. We met up after their Antimatter performance to discuss their work and experiences so far; both artists were present, but Shinichi was more comfortable answering questions in English.

Kyra Kordoski: This is a really unique project. What was the genesis of it? How and why did you start working on it together?

Usaginingen: We were married before we started the project. We moved to Berlin in 2010. Before that, we lived in Tokyo, where I worked in a hospital as a radiographer, and Emi was a graphic designer working in advertising. Emi wanted to live in a European country for a while, at least once in our lives. We just thought it would be an experience.

During the first and second years in Berlin, we tried to find Emi a graphic design job. We brought her portfolio with us to parties, passed it to people everywhere, but unfortunately, she couldn’t get any offers. The German sense is very straight and simple, but Emi prefers to make more playful things. There are a lot of musicians in Berlin, though, and some of them, when they saw her portfolio, wanted to do real-time performances with her. The first guy who suggested it was Japanese. He had moved to Berlin at the same time as us, so we not only had creative things in common, we had the same kinds of problems: visas, how to get internet, basically everything, because it was a foreign country. So, we were kind of on the same wavelength in a lot of ways.

KK: Many designers and visual artists might have gone down an animation software or video production route when thinking about translating their work to something in real-time. Your machine is an astonishing approach.

U: Emi doesn’t like to use computers, and she’s actually not very good at using digital things! It’s the same in her graphic design work — she draws more and makes more handcrafted elements. Her machine, TA-CO, has layers, so the idea was from Photoshop, but it’s like a totally mechanical version of the program. And she also just had the idea that she wanted to ride something, like a bicycle.

I remember the day she first showed me some really rough sketches. I thought it could be interesting if it were real, so I asked my father to make it with us because I didn’t have any woodcutting or soldering skills. It’s not my father’s job, but it’s a serious hobby for him. It’s really a simple machine in the end — it has only the Plexiglas layers and the drum.

KK: How did your music become part of things, Shinichi?

U: The first year, she collaborated with musicians in Berlin, and I supported her — I went to the venues and helped put the machine together, sat in the audience for every performance. And then that started to get boring, so I told her I wanted us to perform together. When I was in university, I played bass guitar, and I produced music a little bit. That was it. But we built a machine for me. SHIBAKI has a midi controller, percussion elements, and an electric string instrument. It has two strings. I use Ableton when performing and Logic for the music I produce in advance, to be mixed in during the live shows.

KK: Your performances are an incredible synthesis of sound and visuals, human and machine performance… You use electronic devices, but what you do is so far removed from just sitting at laptops. There are a huge number of components, but everything is so effectively integrated. Did you have to put a lot of work into finding that kind of overall balance and flow, or did it seem just to come quite easily?

U: Because we were married before the project, we’d already spent a lot of time together, and we are always trying to be equal. I don’t want to fit my music to her visuals or vice versa. We want to make something together. So maybe that’s one reason. We usually perform at digital media arts festivals, so people watch digital things all day, and we’re always the exception. It seems to come across as very classic and nostalgic.

We tried having the visuals just projected onto a big screen the first year, and we performed beside it. Then a guy told us after one performance that he was really tired from looking back and forth, trying to watch both the screen and us, so we thought, OK, we should come forward onto the stage more. We also started using shadows, reflections, and light to bring the visuals out into the whole performance space, to create a total atmosphere. My music is about 50% improvised, but her machine isn’t fit for improvisation because you need to prepare all the materials for it in advance. She never remembers my music structure, so that doesn’t help her keep track of her sequences. Her approach is to practice a lot and put the actions into her body as muscle memory.

KK: You say in your brief artist statement that you “express [your] respect to the animals, nature, and humans.” How do those ideas — animals, nature, and humans —inform what you create? Are different performances built from specific concepts or narratives?

U: With the first set we performed at Antimatter, Pendulum, it wasn’t a strict concept. But our general idea with that one was exploring different perspectives, seeing the same thing in different ways. It was loosely based on a trip to Egypt. While we were there, a Japanese journalist was arrested by ISIS. Before that, we’d felt really comfortable there. It was very new but comfortable. After we heard that news, there was an element of fear. So, with this performance, we tried to make something that shifted frequently and always had two faces simultaneously. The second set, Bath, was created after we’d traveled to Iceland and we were thinking about global warming. We used water, a lot of fire-like visuals.

When we lived in Tokyo, our top priority there was working. After we moved to Berlin, that changed. We thought we needed more time to feel… everything… and not just constantly rush around and spend money on clothes. We didn’t have a job for a long time after we moved, so we talked a lot about life, Japan, culture, politics — which was also, in part, because we’d touched a different culture there. Lately, we’ve been thinking more that we are like a part of nature. And also, she just likes animals. She has a lot of animal kitchenware and designs animal things all the time.

KK: You also mentioned on your blog that you find you receive different reactions when you perform in different countries?

U: Latin people have a very direct reaction. English people are really into the music side of things. Japanese people are really quiet during the performance, but afterward, if we talk to them face to face, they tell us they enjoyed it. When we perform in European countries, people say it feels Japanese, and when we perform in Japan, they say it seems quite European or German. But children, they’re all the same in how they react. They don’t ask many questions, but during the performances, they really respond to the specific elements: water, an apple… I remember one funny question from a junior high school student. She asked us, “What is your relationship?” She was a teenager, so of course, she was interested in relationships.

In Japan, we often perform in schools — from nursery schools to universities — and we speak a little after the performances. Since the 2011 Tsunami, I think people's ideas about what they want, their ideas about their lives, have been changing. We have many friends who moved out from Tokyo to the countryside. These performances are part of our own exploration of this phenomenon and, especially when we perform to young audiences, we want to express to them that they can try to do whatever they want. Before, it was just accepted that you go to school, go to university, and work at a big company. We used to do that. I used to work in the hospital, and she had a really ‘good’ job. But we quit. And somehow, I want to show these kids the possibilities of their lives.