Last year marked the hundredth anniversary of the birth of Paul Celan, often called the greatest of postwar European poets and the fiftieth of his death. Perhaps for that reason, 2020 also saw some important English-language publications on Celan: The Luxembourg-born American poet Pierre Joris capped a lifelong project of translating Celan’s oeuvre with the release of Memory Rose into Threshold Speech: The Collected Earlier Poetry (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux) and Microliths They Are, Little Stones: Posthumous Prose (Contra Mundum Press), while the legendary City Lights Books released a new edition of the French poet Jean Daive’s Under the Dome: Walks with Paul Celan (1996), in Rosmarie Waldrop’s translation, originally published in 2009. Finally, on November 23, Celan’s birthday, Duration Press issued another book by Daive, a collection of texts, Paul Celan: les jours et les nuits, translated by Norma Cole.

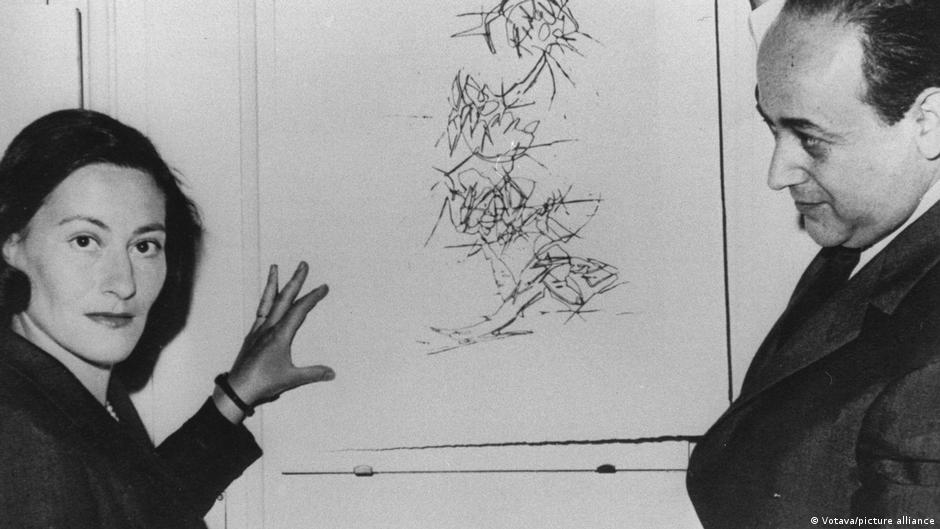

If one calls him the greatest postwar European poet, it might stand to reason that he is also the greatest postwar German poet. But not so fast. He was not German, and never lived in Germany (or, except very briefly, Austria), though his mature writing was entirely in German. He was born Paul Antschel in Bukovina, part of what was then Romania, now Ukraine — a member of a German-speaking Jewish minority. After the German invasion, his parents were sent to camps where they perished; he survived in a labor camp, and following the war made his way to Bucharest, where he came into contact with avant-garde literary circles, strongly influenced by Surrealism, and wrote some poetry in Romanian. In 1948, he settled in Paris, where he would live the rest of his life, and published his first book of poetry, in German. He married Gisèle Lestrange, an artist, and became a French citizen. In 1970, he drowned himself in the Seine.

Celan, therefore, wrote always as a foreigner. His use of the German language was always estranged and estranging. It never strove to sound natural. “Among the basic characteristics of poetry,” he once wrote, “is that it knows itself to be exposed to misunderstanding.” Because of this, his work acquired a reputation for difficulty, but that’s misleading if it implies that his is an ‘intellectual’ poetry; on the contrary, what we might experience as torsions or distortions of language register the extremity of emotion; rather than speak of difficulty, it would be better to say, simply, that one never knows in advance how to read this poetry: One can only learn how to read it by reading it. And if it resists being read, that resistance itself becomes something to be read. As Daive writes, “Paul Celan chews a word like a stone.” We too have to break our teeth on them.

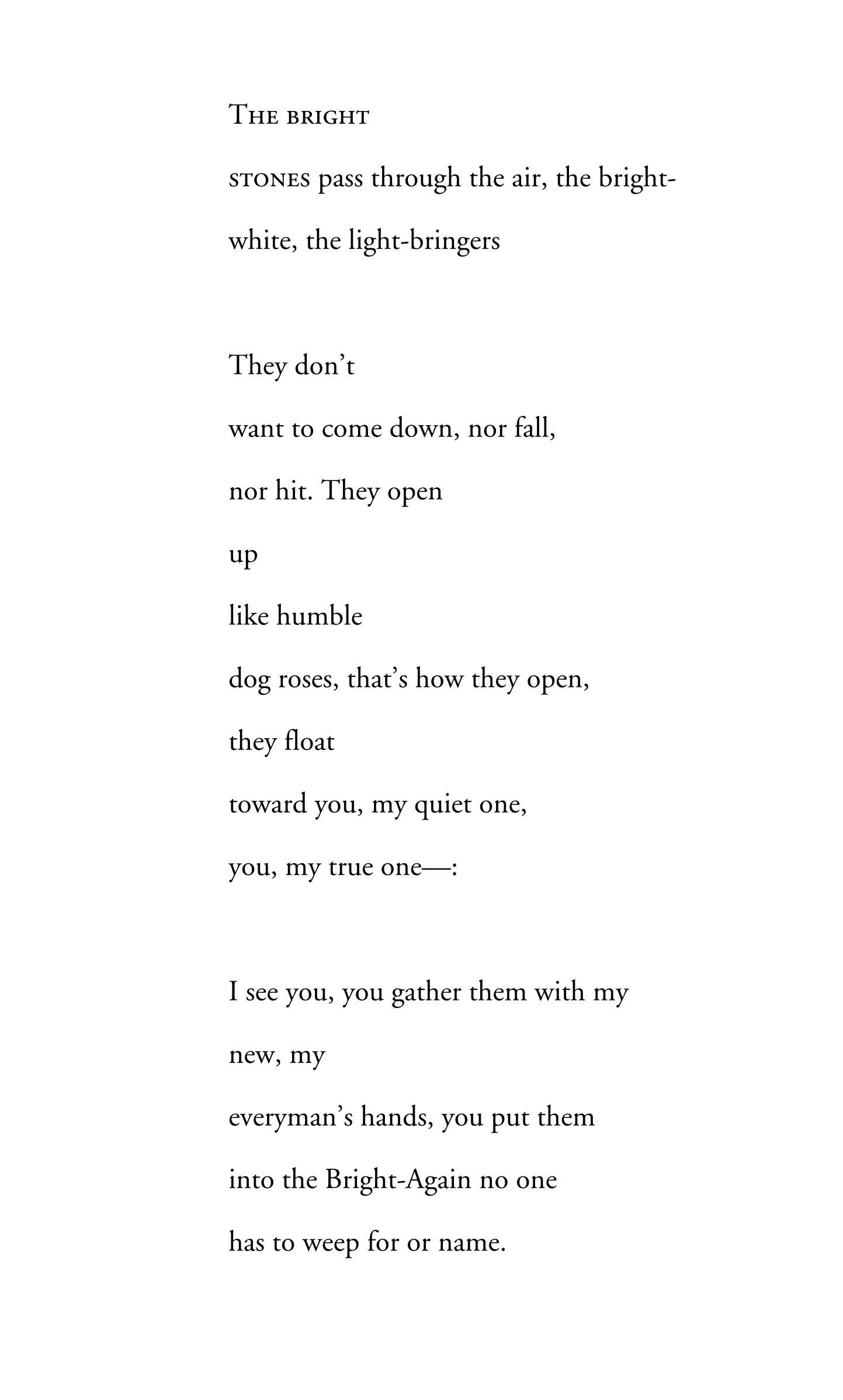

Words as stones we find, I think, in a poem like this one, which I quote in full, from the 1963 collection Die Niemandsrose — in Joris’s translation, “NoOnesRose” (as with many of Celan’s poems, the poem’s title is not separated out from the body of the text, but consists of its first words rendered in small caps):

What’s immediately apparent is the ardent intensity of address embodied in this poem. It’s less evident who is being addressed, who is doing the addressing — and for that matter, the poem ends by deliberately blurring the distinction. When speaking of the “white stones” floating in the air as “light-bringers”, which I take to be the words of the poem itself, which come not from the poet but as it were from the space around and in between the poet and the one addressed, the beloved, he declares that “you gather them with my… hands” that are anyone’s or everyone’s.

The intensity of longing is palpable in this poem. One could easily read it as an implicitly erotic longing, perhaps in that immemorial genre where earthly love becomes a figure for spiritual yearning; the “Bright-Again” where there is no weeping could well recall the Book of Revelations in the Christian Bible: “And God shall wipe away all tears from their eyes; and there shall be no more death, neither sorrow, nor crying, neither shall there be any more pain: for the former things are passed away.” As the poet John Wilkinson writes in an essay first published in 2007 and recently reprinted in his book The Following (The Last Books, 2020) — he is speaking of an earlier Celan poem, “Engführung” (Stretto) — “a flurry, mere linguistic shadows upon the stones, allows the stones to sing, gives the stones the power to mend the breach.”

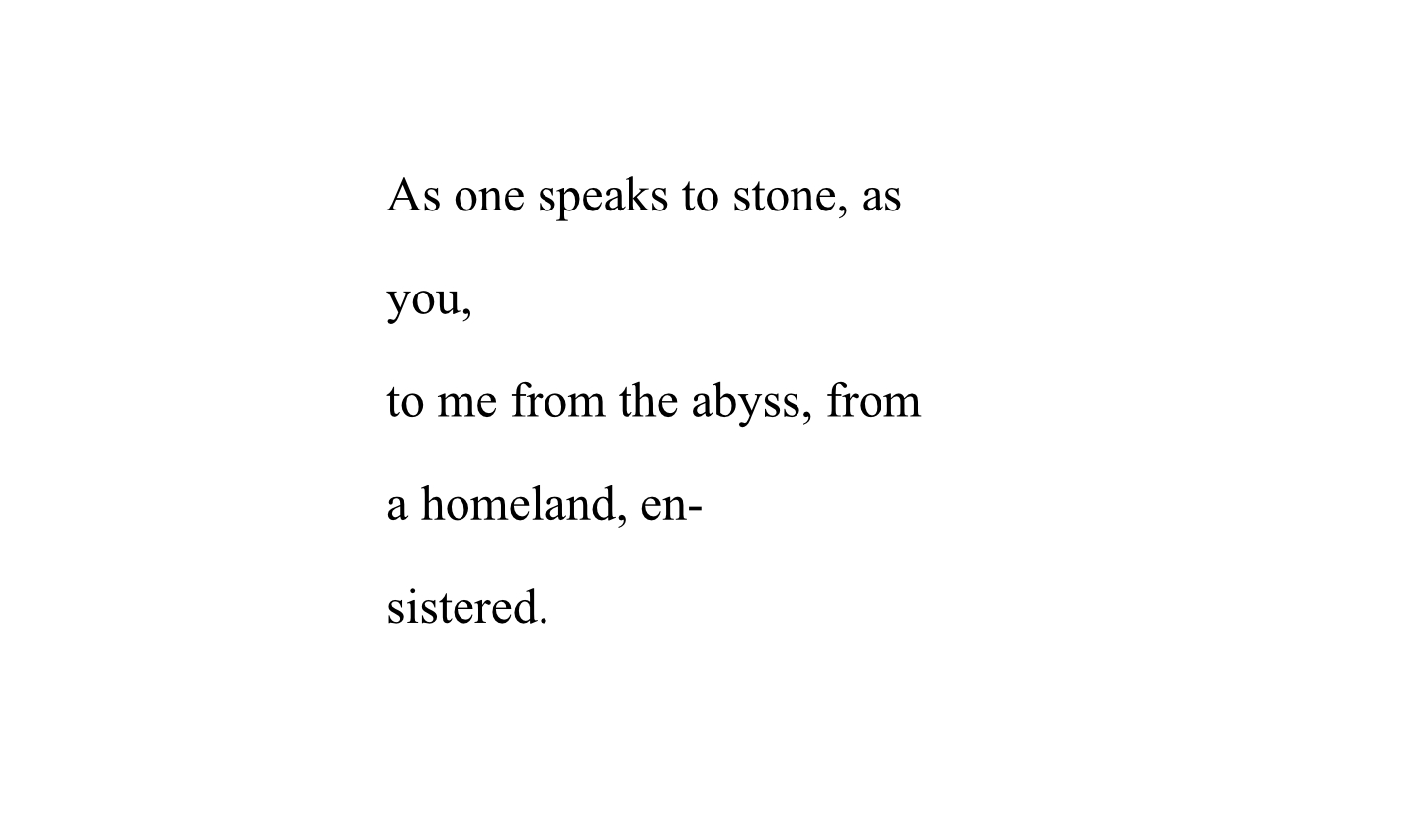

But as “Radix, Matrix”, yet another stony poem in NoOnesRose, perhaps makes more evident, the ultimate addressee of “The bright stones” — as in so many of Celan’s poems, and despite his manuscript dedication of this one to his wife — may, in fact, be his mother, murdered decades before by the Nazis. Or perhaps he was the addressee, she the speaker — again the “you” and the “me” are:

Lover, mother, sister — whoever or whatever she is, the interlocutor is always female. And yet the presumably male speaker feels so intensely identified with her that it becomes understandable that the Lacanian psychoanalyst Ruth Golan has speculated that Celan was one who crossed the nebulous boundary between the sexes, who “touched upon feminine jouissance and knew something about it”. Again, at the end of “Radix, Matrix”, in a partial return to its opening, the distinction between the female “you” and male “I” grows faint as the stone falls into a hand:

Is something as hard and recalcitrant as a stone also a nothingness? When the stone is a word, yes. In Paul Celan: les jours et les nuits, Daive recalls his friend saying this: “Man is without words. He is perhaps born from words, but he loses them. Life makes him lose them.” Just as one is born from a mother but loses her. With whatever trustworthiness, Daive’s recollections evoke Celan as a man whose everyday speech, strangely formal in a way his poetry is usually not, was nonetheless always, in itself, poetry. Or perhaps Daive can’t help but translate his memories of Celan’s conversation into a kind of poetry.

The poems Celan actually wrote have been translated into English many times by now — starting in 1955 with a version by the art critic Clement Greenberg of what is still Celan’s most famous single work, “Deathfugue”. In 1969, Cid Corman published unauthorized translations of eighteen poems, and in 1971 a book of selected poems translated by Joachim Neugroschel appeared. But the flood really began in the 1980s; among those who have translated substantial quantities of the work are Ian Fairley, John Felstiner, Susan H. Gillespie, Michael Hamburger, David Young, and the team of Katharine Washburn and Margret Guillemin. All these versions are worth reading; each refracts the poems’ light in distinct ways. Though hardly fluent in French, I’ve also benefitted from the versions rendered into that language by Jean-Pierre Lefebvre, which (precisely because I need to work through them by way of the dictionary) restore to the poetry a dimension of foreignness that any translation into one’s own language will tend to diminish. But the completeness and thoroughness of his effort aside, Joris is now the privileged conduit for Celan’s poetry into English, thanks to the acid-etched clarity of his language as well as the extensive and helpful notes he has appended to the poems.

I asked Joris how his passionate involvement in Celan’s work, now more than fifty years long, came about. He explained that in high school, he had been exposed to modern German poetry, remaining unaffected by it — until he read Celan: “I had maybe the only epiphany of my life — my hair stood up on the nape of my neck. The absolute realization that there was another way of using language — not how we used it every day at home or on the street, not ‘literature’ between quotation marks, either. This was something else.” A language that speaks more intimately than any other, almost without defenses, perhaps. But remember, to feel the hair standing up on the back of your head is a sign of excitement, but also fear. There’s something terrifying about giving oneself up to a language so exposed. But once experienced, it can’t be forgotten, and one longs to return there.