How to describe the work of the creative polymath Pavel Pepperstein? To engage fully with the Russian artist’s oeuvre, one may be required to suspend disbelief. It is a conditional surrender to the provisional laws of an alternate universe—one in which the artist’s private cosmos orbits so eccentrically that it escapes the gravitational bonds of historical time and space.

Described variously as a painter, writer, critic, art theorist, fashion designer, and rapper, Pepperstein is considered one of Russia’s most influential artists of the contemporary era. Boris Groys writes that he is—above all—a “designer of social spaces.”

Pepperstein grew up amidst the underground intelligentsia of the late Soviet era. His father, Viktor Pivovarov, is one of the founding members of Moscow Conceptualism, while his mother, Irina Pivovarov, was a poet and author of children’s literature. Both are prolific illustrators of picture books. The writer Michail Ryklin has remarked that, “Moscow Conceptualism to a large extent originated from the illustrations of children’s books. Pepperstein was growing up, one might say, in the epicenter of this process…”

Coming of age as an artist in the 1980s, as the Soviet system was on the point of collapse, Pepperstein has maintained a critical stance towards the influence of Western culture. In 1987, he co-founded the artist group Inspection Medical Hermeneutics to resist the accelerating Western influence on Russian life. The collective undertook a critical examination of Russian culture during the Glasnost period (1986–1991) when the country opened up to the West.

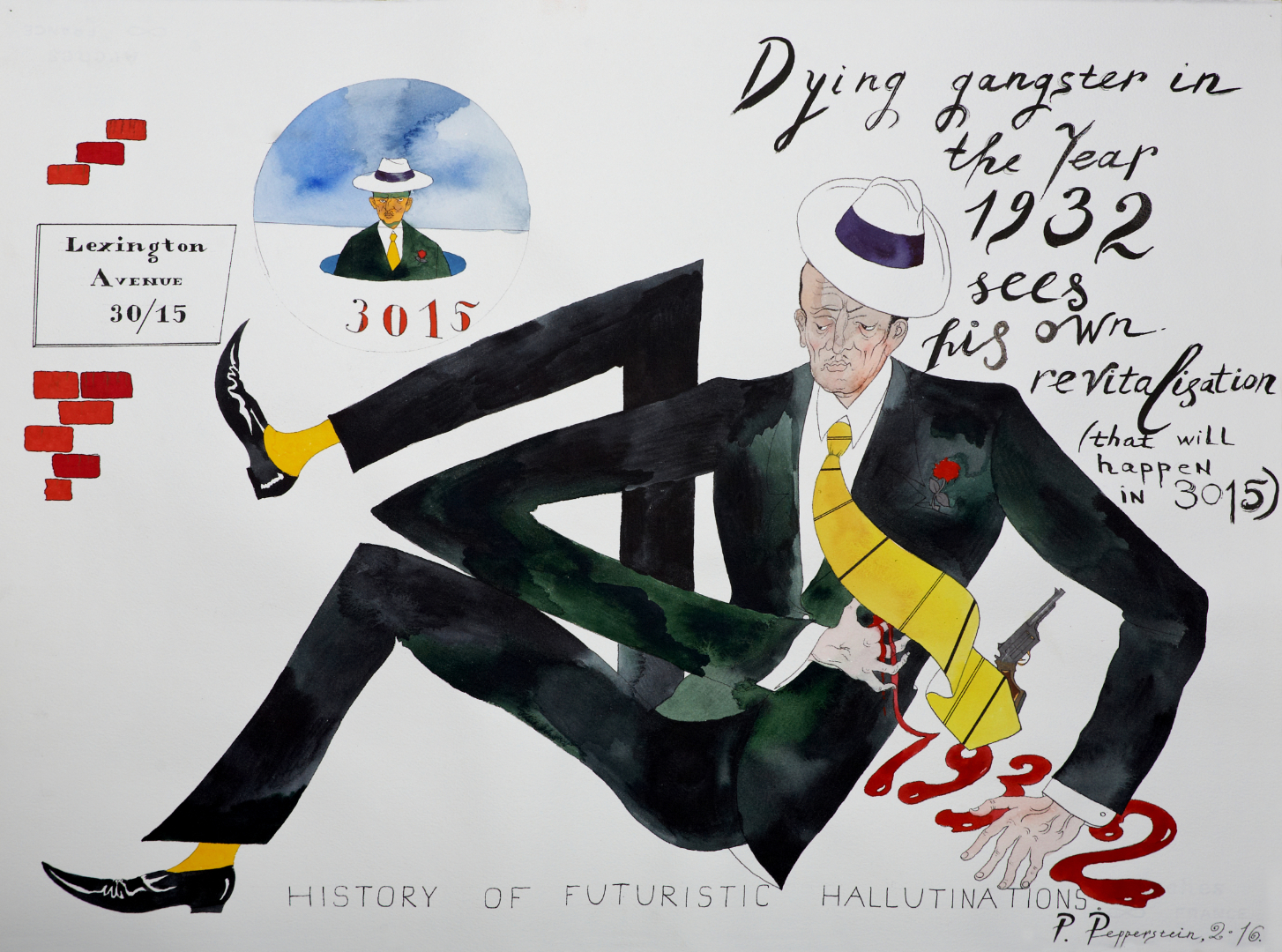

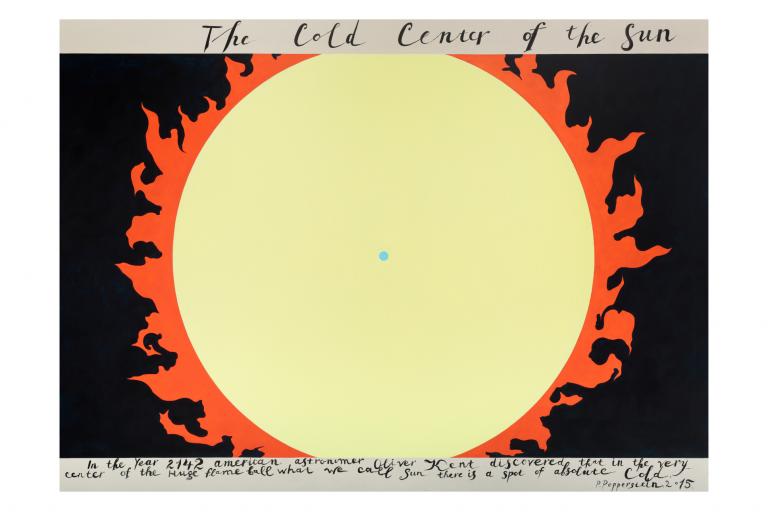

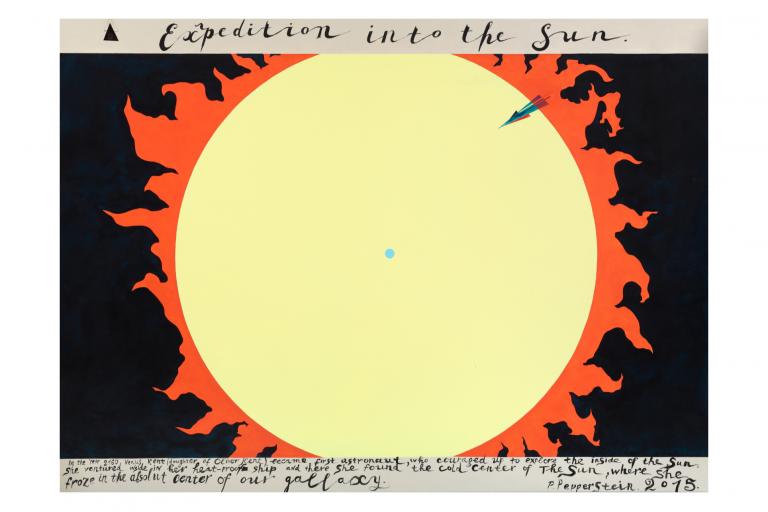

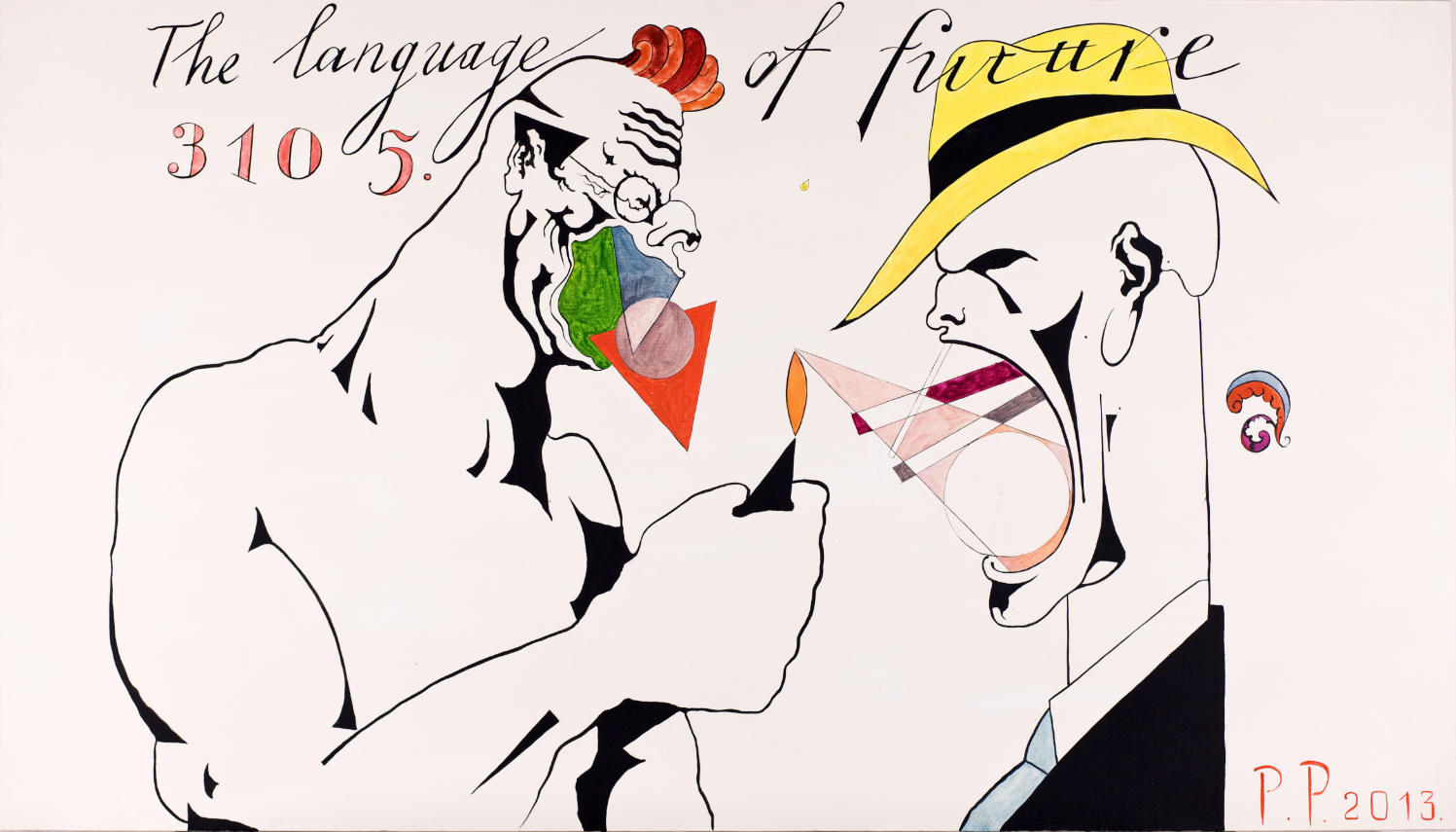

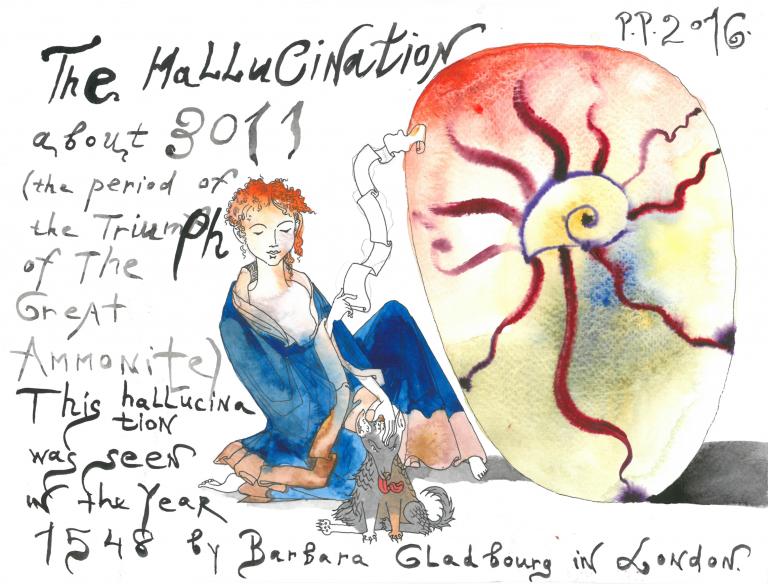

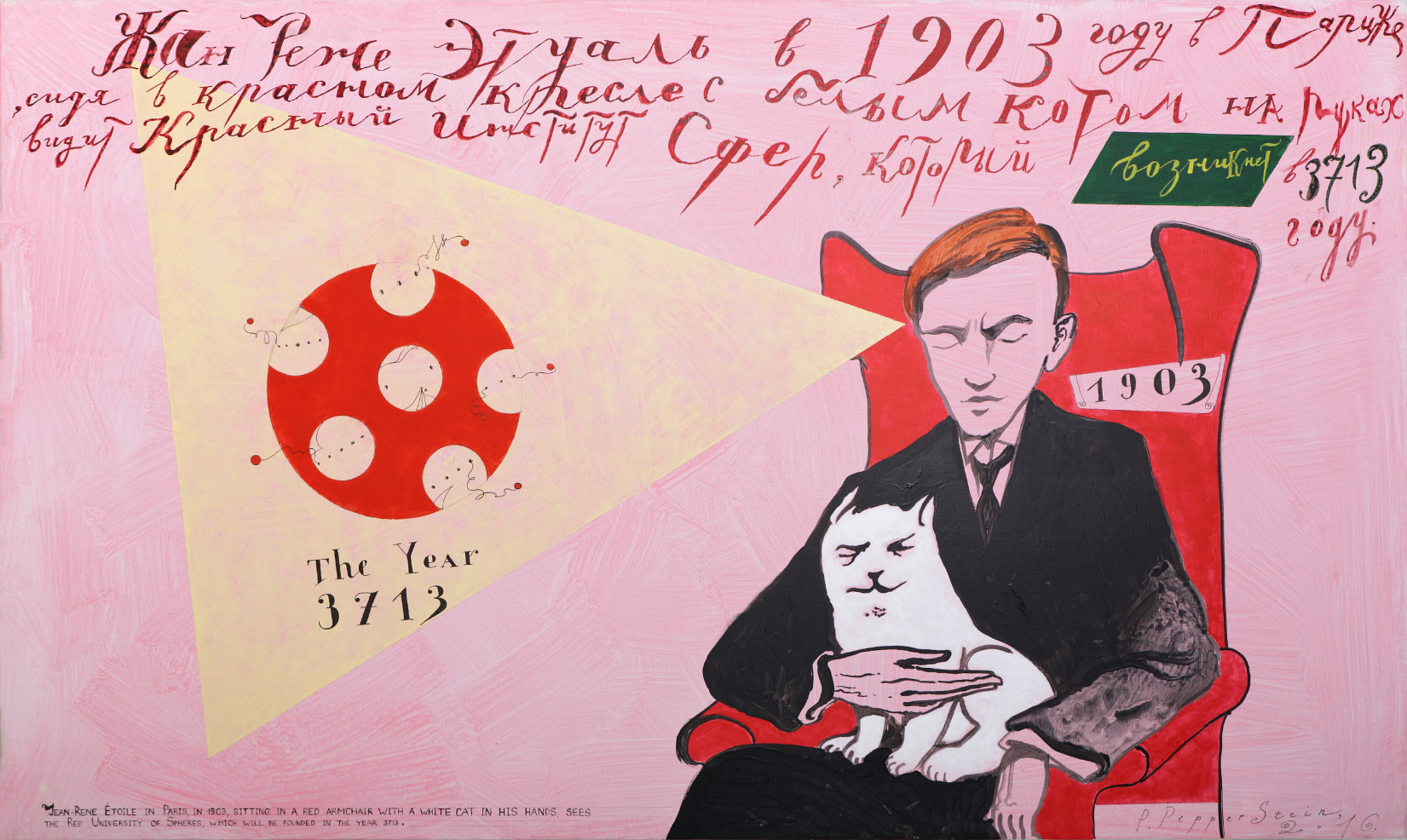

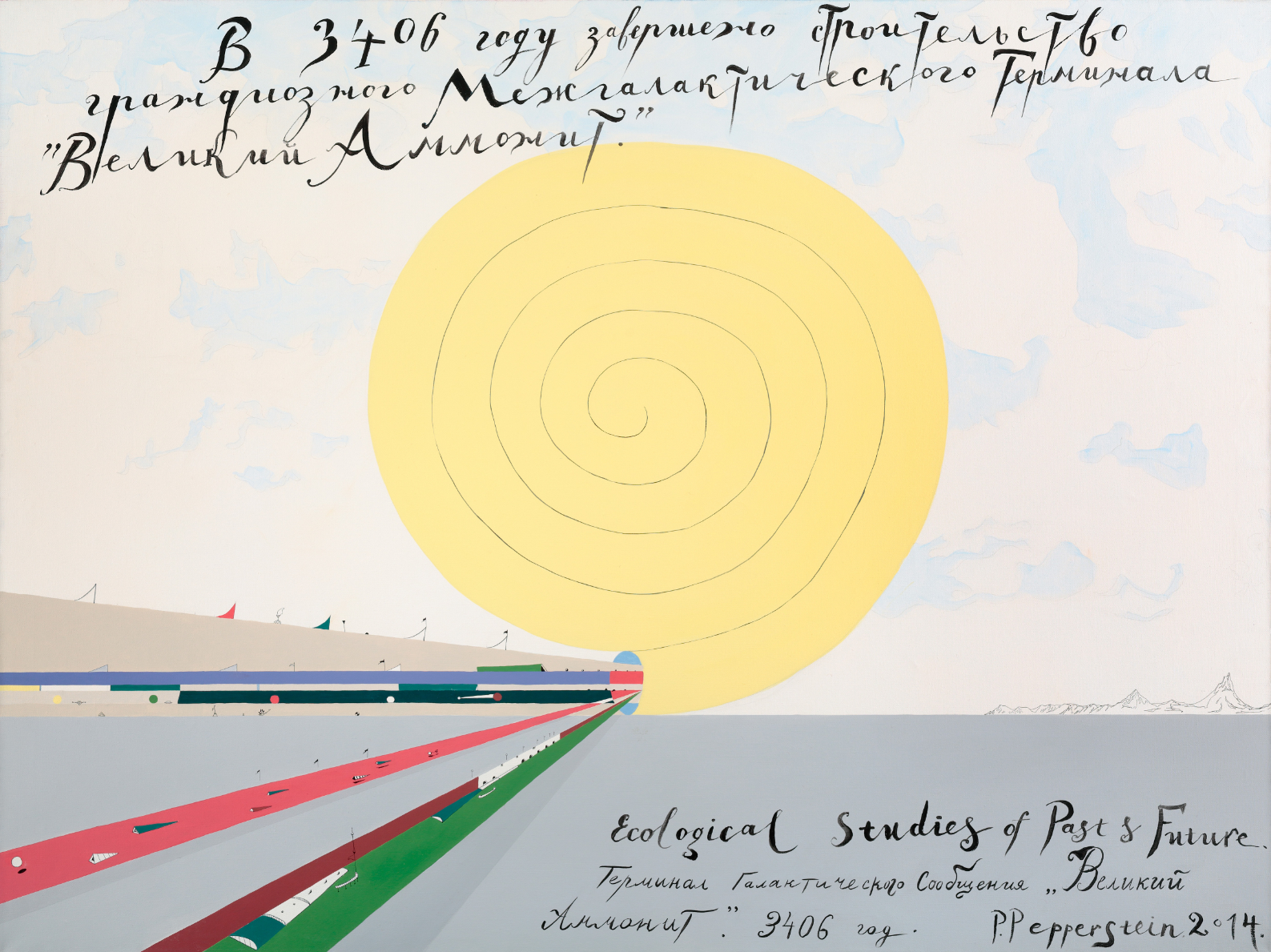

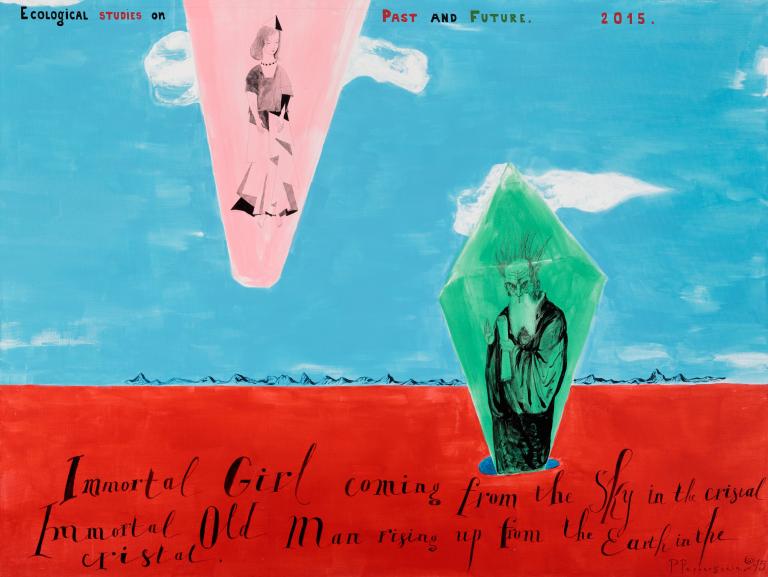

Pepperstein engages in what he refers to as “psychedelic realism.” In the creation of his new unbound worlds, his appetite for stimuli is seemingly insatiable. His artworks abound with free association, cultural and political symbols, textual annotation, and allusions to such phenomena as Surrealism, Malevich’s Suprematism, Eastern ink painting, pop art, book illustrations, and political caricature. In an interview conducted in the autumn of 2020, Roger Boyce dove deep into this protean figure’s mind.

Roger Boyce: Over the past decade or more, the contemporary art world has witnessed a resurgence of drawing—a primary means of making, eminently capable of summoning retinal delight while simultaneously shouldering weighty conceptual freight. In that light, the works of Marcel Dzama, Jim Shaw, Raymond Pettibon, and Jeffrey Vallance come readily to mind, as do your engaging forays into the medium.

Do you feel your work has any sort of kinship with these notable exemplars of the aforementioned contemporary drawing zeitgeist? Or does your practice differ categorically in sensibility or intent?

Pavel Pepperstein: For years now, I’ve been delving into an apparently deep abyss between word and image. The ever-changing territory of language summons entire, abundant worlds. My images may be seen as a sort of fruit of such worlds. But in turn, images are themselves a fruitful source of words.

My works wander purposefully through different fields of endeavour, meandering through culture, literature, illustration, etc. Especially the sorts of illustration found in children’s literature, because children’s tales and illustrations deal frankly with the subconscious and, of course, with psychopathology.

Studio procedures for working out ways of elaborating and elucidating divergent sensibilities open up special channels to understanding how all of this works and how diverse fields can be made to come together. Coincidence itself is very fruitful, very productive. But what conceptual art has to do with that is problematic.

When asked about my work, I often say it is a childish way of understanding—a fruitful means of subjectively responding to hard, objective realities. Different artists have, of course, inspired me in various ways, but I prefer not to cite particular names, because, somehow, who strikes me is not so important. Inspiration from other artists could be fairly characterized as a challenge, so to speak. But more in the how than the who, as such challenges arise more by accident than by design.

And at any given moment, one can never really know what or who might inspire. Inspiration might, for example, arise from a heady, momentary feeling, from the season, the weather, from hallucination, spontaneous emotion, or ineluctable intellectual configurations. Mixtures of all these elements provide the fabric of my drawings, fairy tales, novels, and movies. So that is my answer.

RB: I’m pleased to see “words” arising in our exchange, as, quite obviously, words—as visual signifiers, as literally readable tropes, as conceptual place-holders—perform a crucial role, both formally and conceptually, in a great majority of your two-dimensional works. As for the particular handwritten words you use, I have questions:

First, why the predominance of cursive English words and alphabetic characters in your image fields, rather than, say, Russian words borne on the back of your native Cyrillic alphabet? Or why not the written conveyance of some other continental language, given your reportedly nomadic lifestyle?

I’m also interested in your citing of hallucination as a sort of fertile, sense-expanding channel—or, perhaps, as an accessible means of summoning temporary states of psychopathology: psychopathological energies leveraged against the more ordered and static constrictions of conventional ideation. Induced hallucination as a sort of psychopathological interlocutor, capable of conjuring “incompatible descriptive language” — a phrase derived from your own ideology of Medical Hermeneutics.

Lastly, Sigmar Polke was reportedly a regular imbiber of psychoactive substances. One could readily speculate that the more pronounced Dionysian passages in his work may have arisen from his tripping tendencies. Would similar tendencies be present in your habits, your practice, and your work?

PP: I use both Russian and English words, Russian and English sentences. Sometimes I also use other languages, but rarely. Sometimes I employ Latin, Hebrew, or Italian. But mainly, of course, English and Russian.

My reason for using English is quite obvious: English, in our time, is considered the international language. If one writes something in English, it is readable and understandable to almost everyone. My use of Russian is also due to obvious reasons—obvious because it is my native language, it provides a feeling of place, a feeling of source. Sometimes I mix English and Russian. So, I think the answer is quite clear, hiding in plain sight: Why? To be understandable. And then there is love. I love both languages. That’s all.

Yes, of course, I can identify with artists who’ve employed consciousness-altering compounds. I, myself, have undertaken a number of experiments with various psychoactive substances— liquids, powders, and so on. And I must confess, I have often used the fruits of these experiments in my work.

So, hallucinations we can define—minimalistically—into two categories: psychopathological hallucinations and psychedelic hallucinations. I think the difference is clear and obvious. The first category (psychopathological) comes from sickness, from a sort of ‘mental damage’… let’s call it that. The second (psychedelic) comes from the inherent effect of certain medicaments or plants, or related things like that.

And of course, the content of hallucinations arising from my investigations could be said to be superficially similar, but the taste so to speak of each is markedly different. You’d hardly confuse one with the other. Unfortunately, I’m not familiar with which particular substances reportedly inspired Sigmar Polke. I can only speak knowledgeably about substances that have personally inspired me. But maybe I shouldn’t speak of this at all? Maybe such things should be kept secret? I don’t know.

RB: Would you kindly give our readers a peek into the origins of Inspection Medical Hermeneutics, the artist group you were a founding member of, and the group’s appreciable contribution to the evolution and international standing of contemporary Russian art—and its influence on art’s socio-political and cultural reconfiguration inside Russia since the dissolution of the Soviet Union?

PP: The Inspection Medical Hermeneutics group was created in December 1987, initially consisting of three members: Sergey Anufriev, Yuri Leiderman, and myself. Subsequently, in early 1991, Yuri Leiderman left the group and was replaced by Vladimir Fedorov. The group existed with this lineup until September 11, 2001, when it was officially disbanded.

Everything started with recording conversations on a dictaphone. We would meet at my house and record philosophical conversations. From this practice, a different one crystallized: the practice of inspection. That is, we would visit various places and give everything there a grade. A very complex grading system was created. There were remote assessments, assessments of prospects, and many other grading categories. But the most important was the HRC: Highest-Ranking Category.

The HRC grade was given according to a spontaneous, totally inexplicable reaction—it was impossible to rationally explain the grade. We started visiting numerous exhibitions, restaurants, and other events, giving everything a grade. And, of course, that included the studios of our painter friends. This way, we created a kind of alternative art governance.

This was during a time when Soviet unofficial underground art started to provoke keen interest in the West. We were constantly flooded with all kinds of personas: art collectors, gallery owners, journalists, and critics. This, of course, unconsciously affected our painters, and they began to adjust to the demands of these “aliens.” We wanted to create a sort of balancing, alternative authority, which, oddly enough, did happen.

There were no official promises to anyone, and it was understood that we were actually just some random guys, just like everybody else. Nevertheless, it worked. Painters from that time and social circle happened to develop a kind of double address: on one side, trying to satisfy aliens from the West—and on the other, trying to receive good grades from the Inspection. But no one knew our grades because all of this was done in notebooks, which were kept secret.

Subsequently, many years later, I was very flattered by a remark from a British art journalist who wrote a review of one of my exhibitions in London. She wrote that I was a member of the Medical Hermeneutics group, which, according to her, slowed down the entry of Soviet contemporary art into the international context by seven years.

I am very proud of this remark. Indeed, seven years is a long time. And if this is at least to some extent true, and we did manage to slow down the entry of Russian contemporary art into the international context for a whole seven years, then, of course, it is a great honour for us, and we have something to be proud of.

RB: Wonderful! Slowing down the entry of Russian contemporary art into an international context for a whole seven years is a delightfully Dadaist accomplishment. May I congratulate the Inspection Medical Hermeneutics group on its successful resistance to the homogenizing power of internationalist art machers?

And let me express here how impressed I am by the inarguably immense and protean range of your creative output—an output that sees you functioning variously as a filmmaker, rapper, novelist, painter, and draftsman, amongst other creative roles.

Do consistent thematic and conceptual threads free-associatively weave their way through all of your various media? Or do each of the polymathic methods you employ call up, shape, or particularly suit certain flavours of the heterogeneous collection of emblematic elements you wildly juggle?

For example, the recognizably reductive visual vocabulary of the historical Russian avant-garde, tropes derived from the go-go-Space-Age sixties, dark and broken narratives extracted from the Great Wars, the charming lyricism and mythopoetic tendencies of children’s illustration, or demotic and sometimes humorous quotes from Hollywood films and the speculative excesses of science fiction?

PP: Your question, if I may put it this way, in itself contains several answers to its own queries. And I will agree with these embedded answers with pleasure, joy, and enthusiasm. Yes, of course, the infinite, or actually finite, forms of my characteristic practice are all connected in this or that way. However, I sometimes endeavour to consciously break these connections and bring into play what was once—in Medi-Hermeneutics slang—called the “stream of free associations,” in order to create a kind of dissociative effect.

However, no matter how powerful the dissociations are, the associations are stronger. This way, everything weaves into a labyrinth-like landscape, through which you can apparently travel, or, of course, choose not to.

Some of Pavel Pepperstein’s answers have been translated from Russian to English by Mark Torochkin.