It’s been largely a private transformation. The shift was forced and unanticipated. Few musical artists love the stage more than Lucas Abela, aka Justice Yeldham. In fact, the artist says, up to now, almost his entire musical evolution had happened onstage in the presence of live bodies. But like musicians all over the world, in early 2020, Abela found himself banished to the bedroom.

As the Covid-19 pandemic began to unfold, I was in contact with Abela. White Fungus was about to bring him and Tokyo noise artist KK Null to Taipei for a performance at The Wall. Abela is one of the world’s most prolific underground touring musicians. By his count, he has played in as many as fifty countries. But he has never performed in Taiwan. Of course, the virus intervened, and the border was closed. The concert, like many of our plans, was shelved. Alas, I caught up with Abela recently to hear how he has been keeping in Sydney and to reflect on his unusual musical trajectory.

I first experienced Justice Yeldham in the mid-2000s at the experimental music venue Happy in Wellington. If I remember correctly, and memory does get a bit hazy, there was little warning as to what I was about to experience. The White Fungus crew frequented the venue in those days. It was a haven for the musically adventurous in a city that was largely disinterested in, or oblivious to, the avant-garde. Upon entering the bar that evening, its founder, Jeff Henderson, told us that someone named Lucas was keen to meet us.

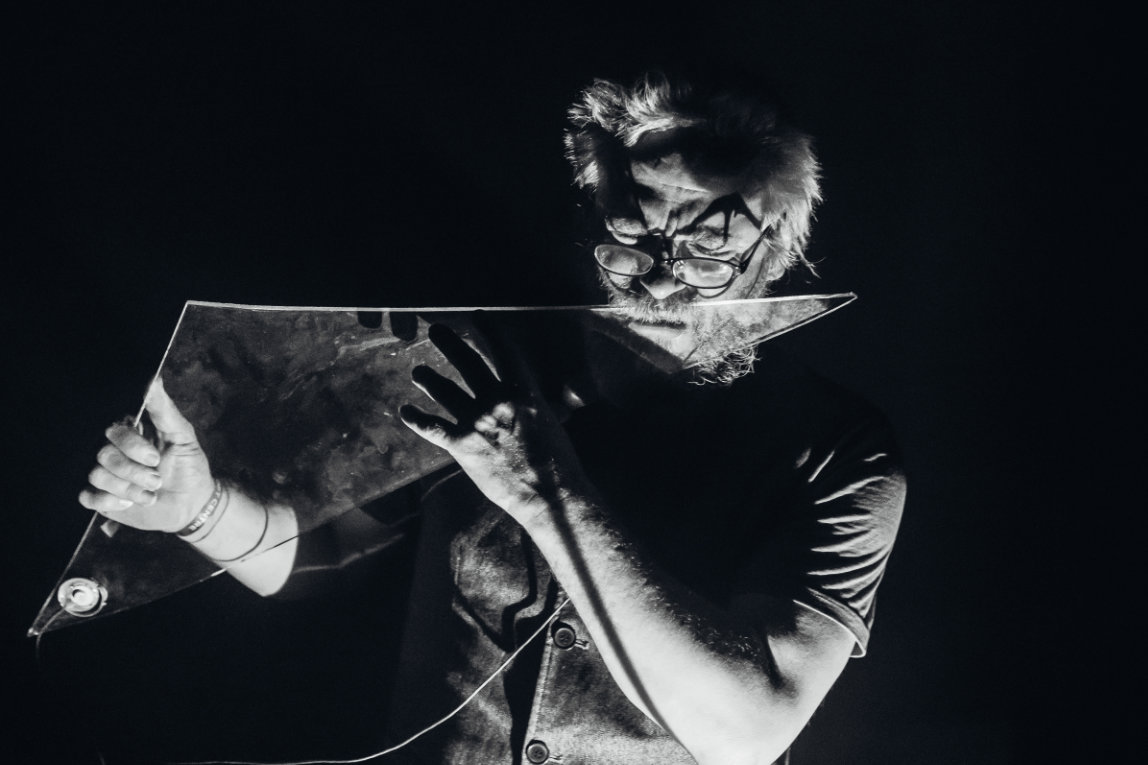

“Who?” we asked. And Jeff pointed to the stage. We looked over at a shaggy long-haired Australian artist with bare feet, who at that moment proceeded to press a scalene triangle-shaped sheet of mic’d-up glass to his lips. Attached to his waist was a super-utility belt of effects pedals. And it was a ferocious sound. It penetrated the entire body. Ranging from high-pitched squeals to rumbling dark metallic tones, Yeldham played the glass with unflinching precision; at least that’s what we hoped.

Through the transparency of the instrument, we could see his squashed blowfish-like face contorting as Yeldham enacted his various vocal techniques. Blood began to trickle and smear across the sheet, and then it began to stream. At the performance’s culminating crescendo, Yeldham smashed what remained of the sheet over his head. Shattered glass showered across the room. The crowd screamed.

It might come as a surprise, given the preceding description, that Abela offstage is mild-mannered, courteous, and soft-spoken. His extreme performances as Justice Yeldham, he says, are in part the result of overcoming performance anxiety. While he is comfortable with blood, he says, it is not his intention to bleed. Rather, it is symptomatic of his choice of medium.

Abela made his first musical experiments in the late 1980s as a teenager living on Australia’s Gold Coast. He had obtained a copy of the Industrial Culture Handbook, a guide to industrial music and performance art published in 1983. In it, he learned of a Boyd Rice (NON) record with an additional spindle hole punched in so it could be played off-axis. Unable to acquire the record, Yeldham sought to replicate it by drilling holes in 7-inch singles he had purchased.

“This led me to do a ton of other bedroom experiments with records,” he says, “slicing them up like cakes and reassembling them, removing the information in the grooves with soldering irons. I even constructed a jump ramp out of cut-up vinyl. I would slice vinyl from the edge to the center and then apply some heat to warp that section into a jump of sorts, giving the needle some air time once every revolution.”

Years later, Abela moved to Sydney and found himself doing a graveyard shift on Radio Skid Row. “I had hours to fill, so I started to recreate those models and build on those ideas. At a point, I stopped dismantling the media and started to manipulate the players instead.

"Whenever I found a turntable in the street, I’d snap off the tonearm, wire the cartridge directly to the audio cable with a phono jack at the end, and plop a pile of them on a record like spaghetti to get an assortment of snippets from the same record all at once. One of my favourite things to do was to place them one by one into the groove like a cartridge centipede to create a huge extended delay.”

One night, the musician and composer Oren Ambarchi tuned into Abela’s show. This led to an invitation to perform at the What Is Music? festival which Ambarchi co-organized with Robbie Avenaim. Yeldham’s career as a turntablist-of-sorts was underway.

Abela’s turntablism continued to evolve. He began replacing the styli with sewing needles and razor blades. Then, he turned to skewers, a Bowie knife, and even a samurai sword. “I had my glove with styli on each finger,” he says. “You could scratch with them in a more warbled way, placing your hand on the record and moving it back and forth.”

Abela replaced the decks with high-powered motors, to which he attached various discs of different textures, including record platters, humming bowls, stainless steel plates, and vinyl. At this point, he says, the music was a cross between turntablism and percussion. He shoved amplified skewers into his mouth and began manipulating them orally.

It was in 2003 that Abela turned to glass. From then, he would take on the moniker Justice Yeldham and the Dynamic Ribbon Device. “I was sound-checking a handheld garden hoe I’d been using at a new space we were opening in Sydney called Lanfranchi’s [Memorial Discotheque],” Abela explained. “We had just finished constructing partitions between the spaces in the warehouse and had installed windows in the walls. During the process, some glass had become broken, and as I sound-checked, it just stared at me, beckoning me to play it.

"Up until that point, I had been going from one instrument idea to another, trying to find sounds I liked. So when I first found the glass, it was revelatory. I was simply amazed by its resonant potential and quickly understood that I had finally found my instrument.

"My preference is to find the glass site-specifically. As soon as I arrive in a city, I start scouring the neighbourhood for discarded glass. The glass size and thickness definitely come into play, and these variants change the timbre of each piece. Thick and big have a better bass resonance, and thin and small, the opposite.

"The glass is played by vibrating the sheet with a variety of vocal techniques I’ve developed mostly onstage. Any sound waves hitting the sheet will have a response, such as a crowd cheering, or drums — which is great when doing a duo, as the beat gets interwoven into my vocals, giving me a heightened sense of rhythm.”

Word of Justice Yeldham performances spread quickly, and he was soon fielding invitations to perform at underground venues and experimental music festivals all over the world. Audience responses were strong and varied. There were instances of people crying or fainting. But others were elated and found it liberating. Abela admits that he enjoyed the performative aspect of putting on a show. He has said that the bloodiest shows were among his favourites, but over time he became disheartened as the music was being overshadowed.

“It got to the point where people didn’t seem to care about the music,” he says,“and just showed up baying for blood. I had complaints when I didn’t hurt myself and even had crowds chanting, ‘Blood! Blood! Blood!’ — which really irked me, as from my perspective, I had invented a rudimentary instrument that, when amplified and connected to some effects, creates organic electronica that’s capable of an immense variety of sounds.”

Abela began to tamp down the performative elements, playing while kneeling with his eyes closed. His musical evolution continued, but the bookings were starting to dry up. Then in 2017, an unusual turning point occurred. While passing through Sacramento on one of his many tours, Abela was invited to record with the popular experimental hip hop group Death Grips. Abela’s contributions would feature on the group’s 2018 album Year of the Snitch.

The collaboration generated an explosion of interest in Justice Yeldham and gave Abela a renewed confidence to continue performing. When he returned to the US in 2019, he discovered he had a whole new young audience, many of whom were only teenagers. He was demonstrating surprising crossover appeal.

And then came the pandemic.“I was in Melbourne for a few shows when it first started,” Abela says. “They started getting canceled just days before they were to happen, which was sad but not as frustrating as having to miss out on Taiwan.”

Abela began participating in the flood of live streams that followed in the wake of the pandemic, but felt a lack of connection with the audience and soon grew bored. “For a musician like me, who considers himself first and foremost a live artist, it was really hard. When I got locked down, I couldn’t play. I still wanted to make music, but I couldn’t go out and do it.

"I started playing at home for the first time in the twenty-odd years I’ve been doing this. I’d never rehearsed. All my musical evolution had happened onstage. Every technique I’ve come up with came from a shared experience. It made me want to redevelop my sound in a sense where it wasn’t all about this loud, live, cathartic, all-consuming sound that I’d produced in the past.”

The result has been Abela submerging himself into a tangle of squelchy, glitchy electronica. By feeding the signal into various parallel audio chains, his previously stark solo performances have turned into a cacophony of wayward accompaniments.

“It’s starting to have beats,” Abela says. “I’m using filters, and I’m using reverse envelopes to squash the filters down, and that’s turning into a kick drum I can control with my tongue.” His performances are becoming longer. For one show at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney, in early 2021, he played an epic three-hour set.

Now borders are open, and Abela is resuming his international tours. He recently returned to Australia after playing several dates in the UK and Norway. In 2023, he plans to tour the world to celebrate twenty years of playing glass. Performances will include two sets. The first will feature his original five-belt setup, while the second will introduce his new modular approach.

“I’m going to showcase this odd journey I’ve taken with the material,” he says. “Admittedly, I originally used glass as a means to make noise, but as an instrument, it’s become so much more.”