In the realms of Taiwanese noise, sound, and media art, no figure is more influential than Wang Fujui. As an artist, publisher, curator, and organizer, Wang’s contribution to establishing these fields in Taiwan has been indispensable. The artist’s biggest early impact was the founding of NOISE in 1993, Taiwan’s first-ever zine and label dedicated to noise. Wang communicated with musicians and artists around the world and connected them to the island’s then-nascent experimental scene. In 2000, he joined the media art collective Etat and launched the BIAS International Sound Art Exhibition.

Today, Wang is most well-known as one of Taiwan’s leading artists in these fields. He has given sound performances and exhibited all over the world. As the Head of the Tran-Sonic Lab at Taipei National University of the Arts, Wang has also ushered in a new generation of Taiwanese sound artists. In 2014, Alistair Noble interviewed Wang about his artistic trajectory. The interview was first published in the 14th print issue of White Fungus but is now available here.

Alistair Noble: I’m interested to learn about your early experiences and education. For example, did you study music? Learn an instrument? Were you always interested in technology, or did this come later?

Wang Fujui: My work came from my love of listening to music. My older brother and I both liked music very much when we were young. When I was in junior high school, and he was studying at the Affiliated Senior High School of National Taiwan Normal University (HSNU), we often bought cassettes, LPs, and CDs together in record stores.

We mainly listened to rock 'n' roll in the earlier period. Later, we could copy CDs onto cassettes after borrowing them, because, at that time, copyright protection was not strictly implemented in Taiwan. We had a SONY CD walkman at home. We often listened to CD samples and rented CDs, and the genres got broader, including jazz and music with stronger experimental qualities, such as releases from the ECM (Edition of Contemporary Music) label. I then entered HSNU copyright protection, spent lots of time on music and films, and gradually shifted the focus of my life from studies to these interests.

I don’t have a formal musical education. Nor did I learn to play any musical instruments. My intrinsic ability for music creation came from massive amounts of listening to music and attending live performances. I studied statistics at university, and at that time, I realized I was not bad at computer science. After graduation, I worked as a programmer for two years. But I didn’t use computers at all in my earliest works. Rather, I used various hardware such as an effects unit, auto mixer, and multitrack recorder.

In 1998, Atau Tanaka performed in Taipei, demonstrating live interaction with sound and images using body sensors, which surprised us. He also showed us the software Max/Msp at ETAT Lab. I then started to learn Max/Msp/Nato, Pure Data/Gem, and electronic sensor-related techniques and applied them to my work. I joined the ETAT Lab in 2000, and we began a series of artistic creations combining technology and media. Since I prefer working with sound, I applied technology to create sound art.

AN: How did you get interested in noise and sound art?

WF: During my music exploration, the genres of music I listened to became broader and broader, and more experimental. I remember it was around 1989 when I started to listen to industrial music. I rented the laserdiscs of Einstürzende Neubauten’s 1/2 Mensch and Test Dept.-Program For Progress at the laserdisc rental center operated by Taipei Pioneer.

One day, when it had been raining in Taipei nonstop for over a week, and I was in a very bad mood, I watched the gloomy film 1/2 Mensch. I wondered if it could be called "music" at all. It was pretty unusual for these two films to show up in a Taipei laserdisc rental shop, and actually, not many people rented them. Later, I bought these two discs when the rental shut down for business. Then, for no particular reason, I started to like this kind of music and began listening to noise music.

AN: I know you spent some time in San Francisco around 1995-1997. Can you tell me a bit about what you were doing there? Was this an important time for you in developing your ideas?

WF: I established the zine and label NOISE in 1993, issuing publications, cassettes, and CDs. I had regular mail communication with experimental musicians in foreign countries, and I was hoping to travel abroad to meet them in person and exchange ideas. I went to study in the USA in 1995 and, in the beginning, settled down in Sacramento. Joe Colley lived there, and he was the first person I met and someone who deeply influenced me.

We went hunting together for music-related equipment like effects units, synthesizers, etc., in flea markets. It was there that I bought my first synthesizer, a second-hand Casio CZ-101. I learned about sound art-related techniques when we chatted at his place, which opened up the path for my work. The first performance I saw in Sacramento was by Joe Colley and Merzbow. Colley’s music tended to explore the possibilities of experimental sound, which was different from violent noise artworks.

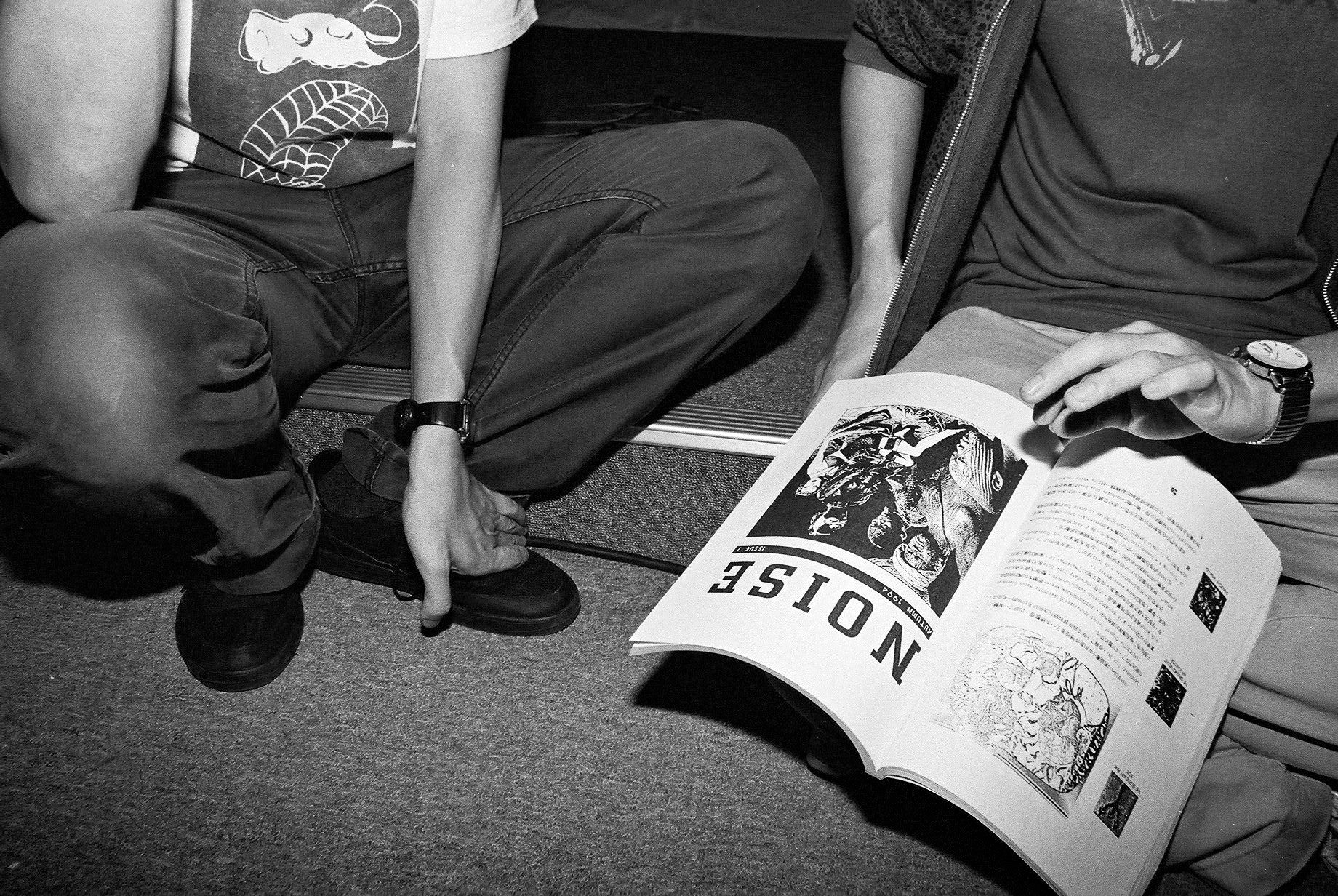

Then I moved to San Francisco and absorbed everything like a sponge. I saw many experimental musical performances and experimental images and had experiences with different subcultures. In the meantime, I edited the last Chinese-English bilingual issue of NOISE magazine, which had interviews with experimental noise artists and musicians around the Bay Area.

I made some good friends at that time, like Scott Arford and Randy Yao. Joe Colley also moved to San Francisco. My early sound artworks were included in the 1998 CD collection Soundtracks For Bride Of Sevenless, issued by Auscultare Research, run by Randy Yao. The biggest thing I gained in San Francisco was learning to open myself up to accept new things.

AN: In terms of people, teachers, ideas, or experiences, who or what would you say are the most important influences on your work?

WF: I think the most important influence on my work comes from life. Although music, books, and films can provide some inspiration and thoughts, it is the actual contact with people, events, places, and things that make one fathom and comprehend, which leads me into different stages of art creation as time goes by.

In 2012, Ron Hanson and Mark Hanson of White Fungus invited me to tour New Zealand. I performed five sessions in four cities. It was my first time performing so intensively abroad in different places, different atmospheres, and with a different audience. The tour allowed all the accompanying performers to appreciate each others’ work, and it was quite touching. I felt deeply each time I saw Samin Son performing, the solo dance of Zahra Killeen-Chance, and the noise art performance of Campbell Kneale. The work of my assistant Lu Yi has also broadened the scope of my performances internationally.

AN: I’ve been thinking about the design and style of your NOISE label releases in the '90s and comparing them to your recent performances and installations. Do you think there is an overall aesthetic in design, art, sound, and technology in your work?

WF: In the early period, most cassettes issued by NOISE were recorded by hand, and the covers were printed individually, then assembled, a bit like the Taiwanese family factories of the 1970s. We once exchanged cassettes with Aube (Akifumi Nakajima) in Japan, and he mentioned in a letter that the cover design of NOISE looked a bit like his style.

I liked the cassettes issued by G.R.O.S.S., a label owned by Aube, so maybe I was influenced by it. At present, when I work on my sound art installations, I try to remove excessive visual elements, so it is a bit minimalist. I hope people can concentrate on listening to the sound without being distracted by too much visual information or excessive decorations.

AN: Many people in the noise/sound field in Taiwan mention you as an important influence, even when their work is very different from yours. Thinking about the people who have been influenced by your work or been your students, what do you think is the most important idea or inspiration that you have been able to give them?

WF: When I wrote an article in a 1993 issue of NOISE introducing the cassettes issued by the Zero and Sound Liberation Organization (Z.S.L.O), we met at the Tianmimi Cafe, owned by Wu Zhongwei [located in Gongguan in the 1990s, closed now]. Z.S.L.O gave some wild performances there, and I also played the noise music of Merzbow, the Gerogerigegege, and others. We later became very good friends and often discussed our thoughts about sound together.

Once, I chatted with Lin Chi-Wei (a member of Z.S.L.O ) on the phone overnight until dawn. Most foreign artists who participated in the Broken Life Festival (1994) and the Taipei Post-Industrial Arts Festival (1995) were either previously introduced in NOISE magazine or had their works issued by the NOISE label.

After I returned to Taiwan in 1997, there was a time when Z.S.L.O., Dino, and I were like a group, organizing activities and performing together. When we were at ETAT, we held Bias, the first-ever sound art exhibition in Taiwan. It was the first exhibition calling for works in sound art and provided opportunities for further development for more young artists.

I then started teaching at TNUA (Taipei National University of the Arts) and became the director of the Laboratory of Computer Music at the Centre for Art and Technology (now the Trans-Sonic Lab). I also collaborated with IO Lab, which was formed by grad students Yao Chung-Han, Wang Chung-Kun, Yeh Ting-Hao, and Chang Yung-Ta, to work on sound-related arts.

I started to organize TranSonic activities in 2008, experimenting with performances that transcended sound art and combined different media. I don’t assign any direction to my students, so rather than bringing inspiration to my students or friends, we encourage and grow with each other.

AN: In the 21st century, I feel that the definitions of noise, sound art, and music are unclear. Sometimes I think maybe there are no boundaries at all. I wonder what you think about this in relation to your work.

WF: For people engaged in artistic creativity, "noise", "sound art", and "music" are just labels to allow ordinary people to easily recognize it. Critics emphasize defining the differences between these different labels. With artworks frequently using different materials or crossing over into different disciplines, it’s very difficult to commit oneself to such a simple means of expression.

AN: In live performances, what sound materials interest you most? (e.g., field recordings, computer-generated, electrically-generated…)

WF: I don’t limit myself to using any particular materials in my artwork. I don’t use traditional methods of composition when I work with sound. I found a unique way to create my works during the process of massively transforming and tuning sounds using computers. I use noise or unusually transformed primary sound sources as my original sound. Then, I use the convolution method of computer music.

Usually, this method results in sounds with various spatial feelings. However, my sampling of modern music, ethnomusic, electronic music, and ambient sounds gives the noise a special musical texture (or feeling), which is like intercourse between noise and music. The generative process requires computation and waiting, and the product is full of uncertainty. It usually takes a tremendous amount of trial and error to get accidentally surprising sounds. I use these sound materials when I perform and make room for improvisation.

AN: I noticed that you seem to have a fairly minimal set of gear when you perform. I wonder if you can describe your favourite setup or some of your favourite equipment?

WF: I often play different types of music and use different equipment accordingly for my live performances. I only use traditional effect units if it’s a noise performance. I bought most of my guitar-like effects units in San Francisco in 1995, including Meatbox from Digitech, Buzz Box, Whammy, and Delay/Sampler.

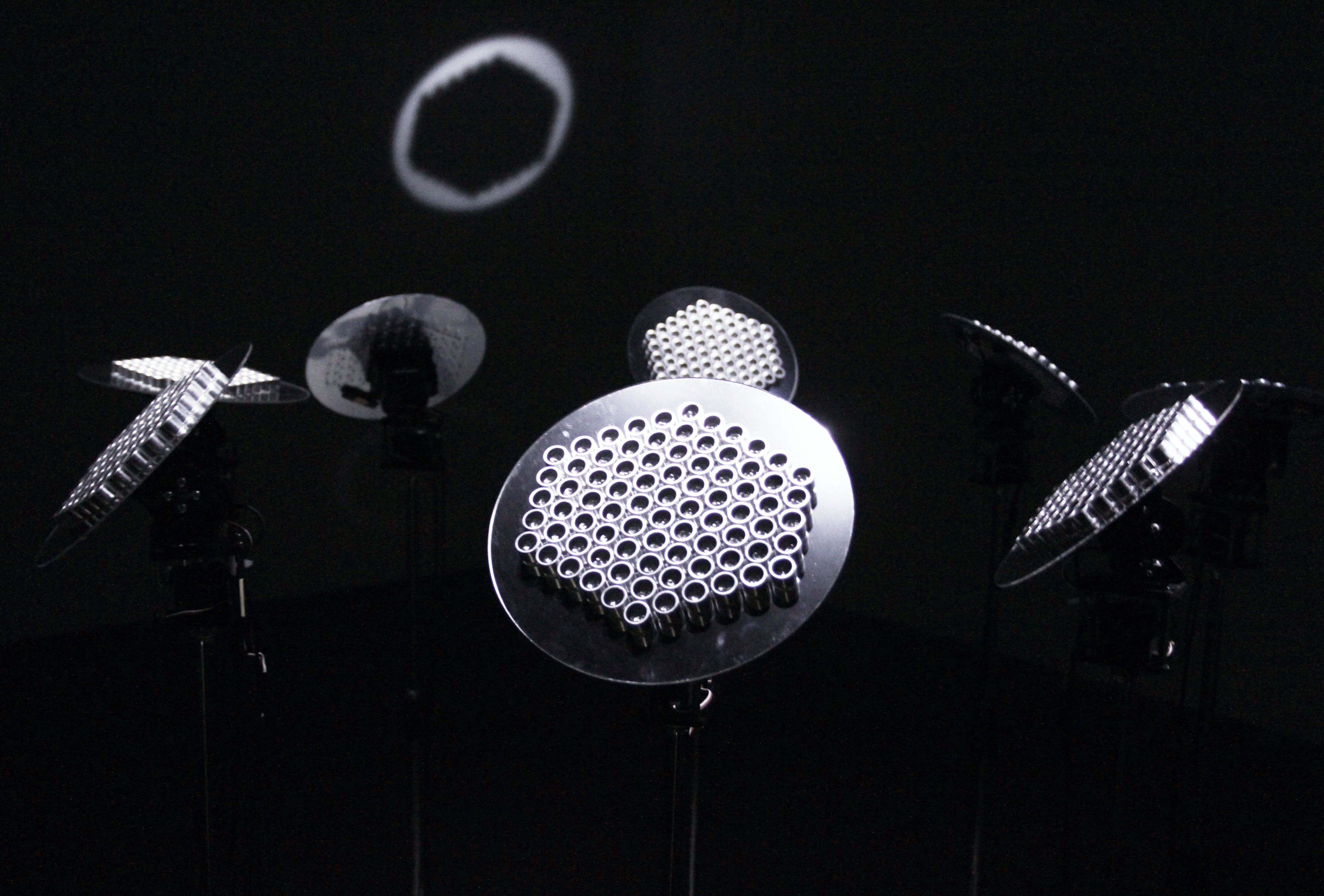

I use a notebook computer when it’s a performance of more electronic-like music, and I use Max/Msp for improvisation. Right now, I often use audio spotlight speakers to generate multiple spatial layers, which gives the feeling of sounds flying past your ears or flowing sideways around your body, the sensation that sounds are constantly flowing around in space.

This is something traditional speakers can’t do. I have seen audio spotlight speakers in sound installations, but have not seen people use them in live performances. Audio spotlight speakers are not without problems: The audio frequency is very narrow, and the sound volume is very limited, so it’s disastrous to use them to play music. I simply use them for their uniqueness; it actually is not that magical in itself.

AN: Your performances seem to have an interesting sense of time structure, and I wonder what you think of the shaping of time in a live performance. Also, I often feel a distinctive kind of rhythm sense in your performances. I’d be interested to know your ideas on that. For example, does it relate to rock music or something else?

WF: When I perform, I emphasize how I, as a performer, interact with the listeners via sound. When I began using a notebook computer more frequently in my live performances, I found that the corporeality of my performances became thinner, and this kind of deficiency of the body also loosens the connection between sound performance and the body. In other words, the performer cannot enter into the condition of the sounds present. How is it possible to communicate with the audience if the performer cannot enter into this state?

This was my thinking when I performed noise concerts in recent years using a guitar-like effects unit. When using it, no matter how violent or cacophonous the noise is, every turn of the knob and every press of the button creates direct feedback. And when the mind of the performer enters the state of the sounds, the body connects to the sounds naturally.

Therefore, I use the dials of a controller or a mixer even when I use a computer. As sounds come into my body, I turn these dials via rhythmic movement of my body, and through these dynamic sounds that penetrate the ears and stimulate the brain and the mind, I let the audience melt into this state with me.

AN: In Taiwan, it seems that all kinds of music and art are naturally political or are interpreted politically. How do you feel about this in relation to your work?

WF: For historical reasons, political activities are especially dynamic in Taiwan. And because of their importance, this brings about democratic progress. When I was an undergraduate, there was a student revolt, and I also participated in a student society for social investigation and gained a deep understanding of the complexity of politics. But, I’m not an activist, and it’s unnecessary to follow the trend of fashionable thoughts when making art. I just look for a path where I can create freely, making this society’s artistic culture more diverse.

AN: Do you think that any aspects of your current work are particularly Taiwanese, either in terms of culture or politics? How do you feel your work translates for audiences outside of Taiwan — for example, in Germany or China?

WF: I have performed at the Transmediale Art Festival in Berlin and the Tonlagen festival in Dresden. The audiences there gave me positive responses, mainly regarding the intricacy and elaborate sound processes. They were especially curious about the flowing, spatial feeling of the sounds I created using audio spotlight speakers. Also, it was refreshing for them because I was from Asia, and they were not familiar with the development of Asian experimental music.

This year, I had a tour of China and performed in Beijing, Hangzhou, Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Macau. Due to more frequent bilateral exchanges between China and Taiwan, at present, we are relatively familiar with each other, albeit with certain cultural differences. The societies in China’s first-tier cities have changed so fast, and people seem to be less interested in experimental music.

I felt this when I compared it to my performance in Beijing’s Mini Midi in 2008. The performance there in 2008 reminded me of the rugged waywardness and passion in the '90s in Taiwan. I also had similar thoughts when having dinner with Yan Jun from Beijing and Junky (Torturing Nurse) and Yin Yi from Shanghai this year after the performances. It’s quite admirable that they are still planning events, scheduling concerts, and making art.

AN: Given that the noise scene began as something that seemed very radical in the 1990s, I’m interested in your thoughts on the process of noise becoming more "establishment" now that people in this field teach at universities, do research, and have work collected by museums. Does this change how you work and how you think about the noise/sound field?

WF: In the '90s, we started from the point of knowing nothing and studied everything on our own. It all relied on intuition and instincts, similar to hammering in the Stone Age. As we accumulated more knowledge and techniques, we could then realize our ideas into artworks.

It was progress, tiny bits of learning, action, and accumulation. And even when we felt everything was in vain, I think that we achieved some results through perseverance. Because of these results, it was possible to be hired to teach in a school or become noticed by an art gallery or a museum.

In terms of art-making, noise, to me, is not just a genre of music. Rather, it allows me to pursue the possibility of various sounds courageously. In the meantime, since I am an artist crossing the analog and digital generations, I hope I can use the almost-forgotten sound-related knowledge and technology I learned in the early days of my artworks to connect in a developmental context and to collaborate with other artists.

Original Chinese text prepared by Lu Yi. English translation by Su Cheng-Wen.

Read a profile of Wang Fujui by Alistair Noble here.