British settlement after 1840 brought a wave of change for the Te Arawa people of the North Island's thermal region. The remote geography of the volcanic plateau initially protected the Tūhourangi and Ngāti Rangitihi tribes from the full impact of the European incursion. But visitors soon found their way to the shores of Lake Rotomahana in search of the fabled Pink and White Terraces.

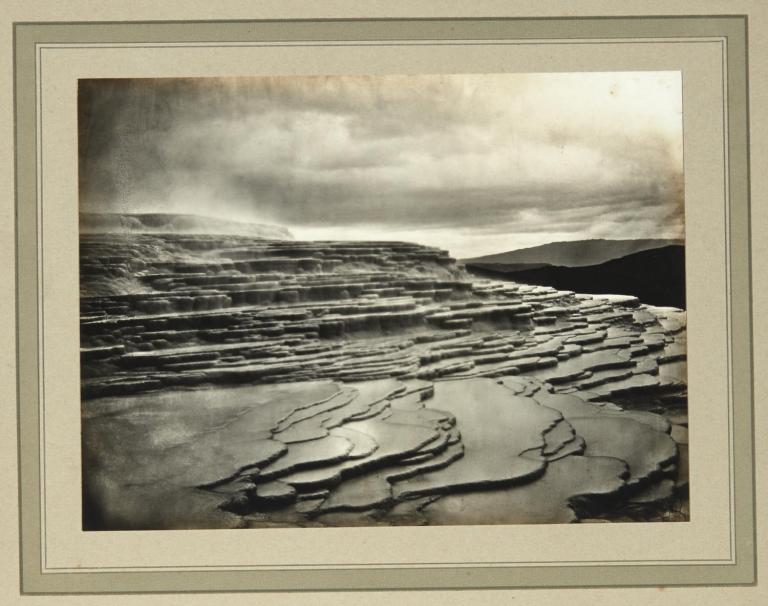

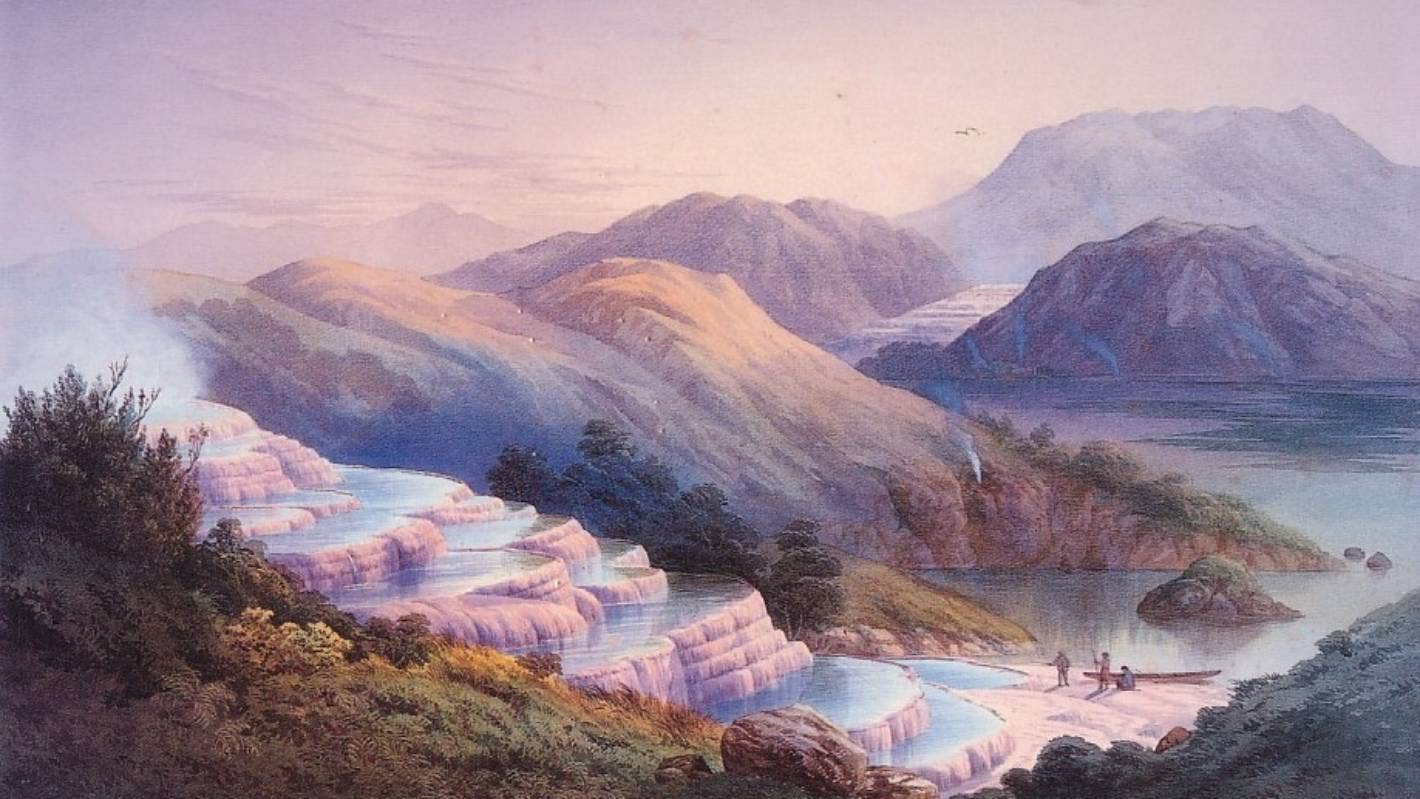

Rotomahana was a small steaming lake adjoining Lake Tarawera, rich in waterfowl, no more than a kilometer and a half long. In two places, volcanic terraces of coral-like silica stepped elegantly down to the lake's edge, created from the trickling waters of hot mineral springs cascading into the lake for over a thousand years. The terraces provided hot pools for bathing and a wondrous spectacle. New Zealand's tourism industry was born here.

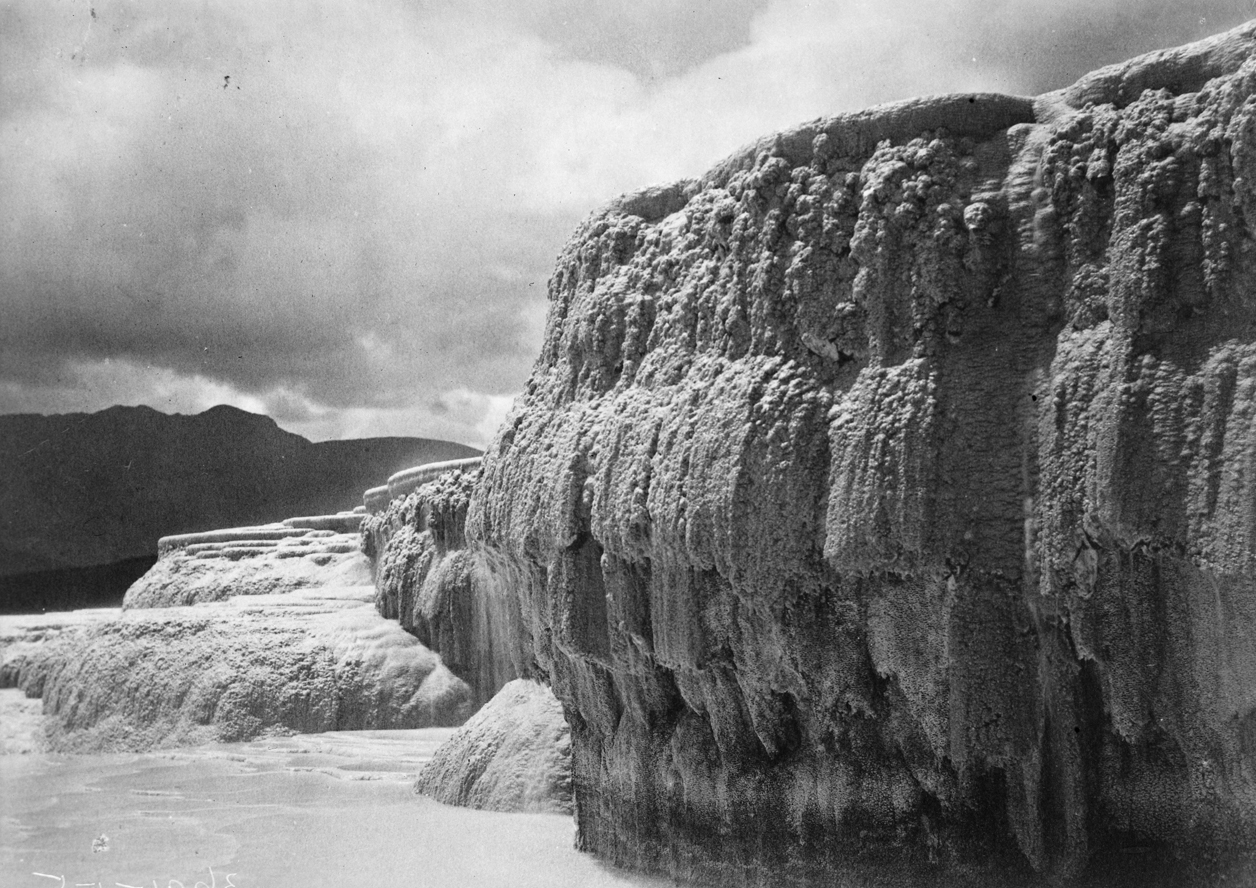

Te Tarata, the expansive White Terrace, is translated loosely from Māori as "Tattooed Rock". In geological terms, it was a white siliceous sinter apron. It fanned out like the tiers of a giant wedding cake from a deep, azure-blue, bubbling geyser pool 30 meters above the lake. Te Tarata covered a stretch of seven-and-a-half acres with pooled terraces of varied sizes, described by one visitor, Lieutenant Henry Bates (a Scottish sheep farmer), in 1860 as "almost too beautiful for this world".

Herbert Meade, a visiting English naval officer, said that "to convey an idea of its beauty is impossible". Others tried. Bishop Selwyn in 1843 likened it to a "frozen waterfall" and Stephenson Percy Smith, a government surveyor, to an "immense surf, 60-feet high just after it had broken". Its multi-patterned and coloured crystalline surface that shone white in the sun was described by one international traveller as a "collection of all the precious stones in the world" and by another as a "raised fretwork of stone, as fine as chased silver".

Colonial surgeon Dr. John Johnson described Te Tarata's oval basins as "adorned by stalactites of a dazzling brightness, reminding one of those ornamental fountains so often seen in Italian cities". They were "filled nearly to the brim with water of an opaline colour, which was continually in the course of change from streams of water pouring into them from a higher step".

Visitors ascended the terraces as if climbing a giant staircase. Dr. Johnson wrote, "The steps commenced, almost imperceptible at first but gradually increasing in height and breadth as we ascended... We had taken off our shoes as the water flows to a greater or lesser depth over the whole surface and found the temperature most agreeable."

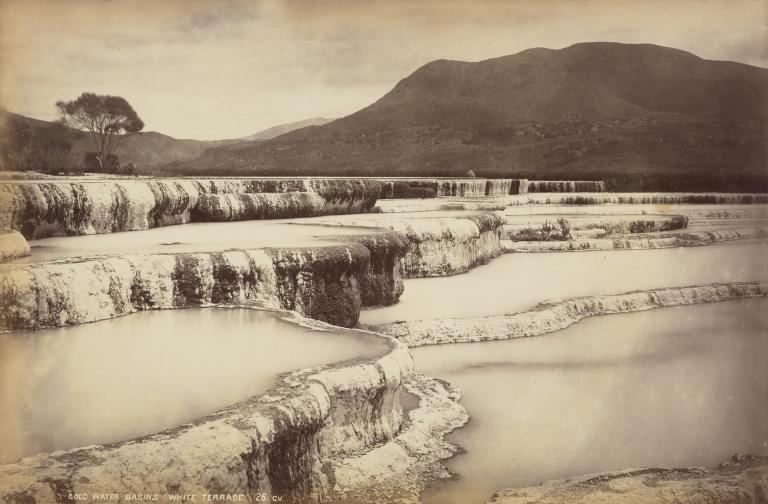

Te Otukapuarangi, the smaller, but some say more beautiful Pink Terrace, translated loosely from Māori as "Fountain of the Clouded Sky". Its summit was also a deep pool and geyser, but its surface was smoother and its buttresses steeper to climb. Painter Charles Blomfield wrote of the pink terrace in 1876: "The colour is the chief attraction. With the morning sun shining brightly on it, it is almost white, but when the sun gets round, and you get more shadow, the lovely salmon colour is very marked... The overhanging lips of the basins are exceedingly beautiful and graceful."

When Victorian novelist Anthony Trollope visited the Terraces in 1874, he observed the special quality of bathing in the Pink Terrace's basins. "When you strike your chest against it, it is soft to the touch, you press yourself against it, and it is smooth, you lie upon it and, though it is firm, it gives to you," he wrote. "You go from one bath to another, trying the warmth of each. The water trickles from the one above to the one below, coming from the vast boiling pool at the top, and the lower are therefore less hot than the higher. The baths are... like vast open shells, the walls of which are concave, and the lips ornamented in a thousand forms... I have never heard of bathing like this in the world."

Trollope speculated as to future tourist development of the terraces, suggesting that the modesty of Victorian bathing could be overcome by reserving the pink terraces for the ladies and the white terraces for the men.

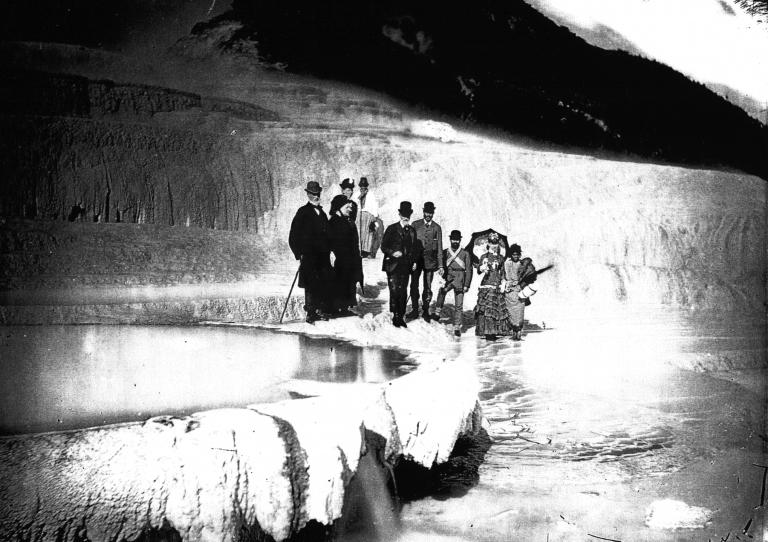

In the mid-19th Century, only the privileged could afford to visit the remote terraces of Rotomahana. The most frequent visitors were overseas tourists and officers of the British regiment. All served to promote the legend of the terraces' wonderous beauty and form. By the 1880s, the Hot Lakes District had become an integral part of the "grand tour" of the colonies for British high society.

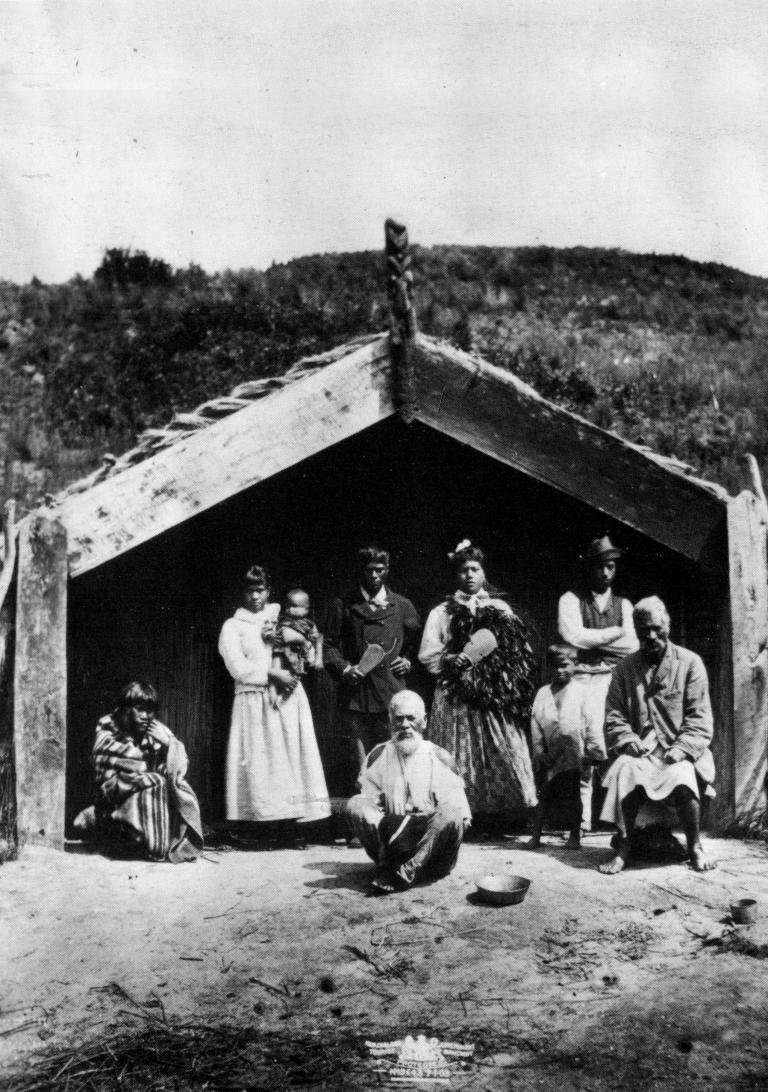

Three chiefly Tūhourangi families guarded and cared for Lake Rotomahana and its thermal attractions. The Rangiheuea family had several dwelling places within the vicinity, notably at Te Ariki, and were its principal custodians. Chief Rangiheuea spent winters on the lake at two small, flax-and-brush-covered islands populated with reed huts. Local Māori understood the hot springs' medicinal properties and visited the islands to bathe in their healing waters.

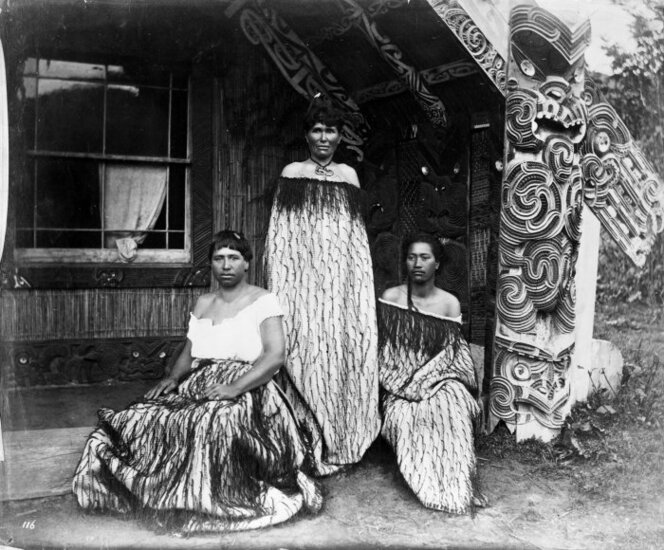

The other caretakers were Chief Wi Kepa Te Rangipuawhe's people and Aporo Te Wharekaniwha's family, Ngāti Hinemihi, guardians of the beautifully carved and painted meeting house Hinemihi on the shores of Lake Tarawera. Wi Kepa was the senior chief of the district. Based latterly at the village of Te Wairoa, Wi Kepa’s tribe provided guides and water transport for the visiting tourists, while Aporo and his wife Ngareta led haka parties who performed and sang for the visitors at the meeting house. Custody of the terraces was periodically challenged and disputed by Tūhourangi's neighbouring cousins, Ngāti Rangitihi. All were of Te Arawa, tracing their descent from the same ancestral canoe.

Te Arawa occupied a band of territory covering the central Bay of Plenty from south of Lake Taupo to the coastal town of Maketū, an important flax-producing town, and trading post. A fleet of Te Arawa coastal vessels operated cargo services between Auckland and the coast in the 1850s. Secure in their roadless country, the inland tribes were still firmly under the control of their chiefs.

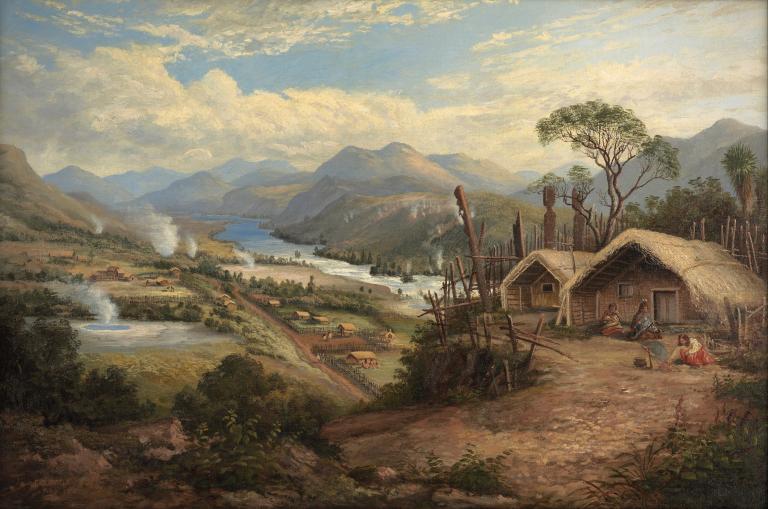

Rotomahana was one of the smallest in a chain of volcanic lakes, including Rotorua, Rotoiti, Rotoma, and Tarawera. The warm and fast-flowing Kaiwaka Stream, full of birdlife — teal, duck, and oystercatcher — emptied into Tarawera from the tiny Rotomahana. The stream was subject to an annual cull in summer but tapu to hunters the rest of the year. In the breeding season, a fence was erected at the stream's mouth to avoid the wildfowl from being disturbed by canoes. Visitors to the terraces traditionally crossed this short distance overland by foot.

In places boiling, the lake itself was warm and swampy, with the occasional spout from a puia or geyser rising from beneath its surface. Besides the terraces, other unusual craters, puia, and fumaroles dotted its surroundings and encrusted silica "pavements" flanked its shores. The hillsides were covered in fern brush, the lake with raupo and reeds. Beyond Rotomahana (the "Hot Lake") was the even smaller Rotomakariri (the "Cold Lake"). Above the lakes towered the vast black hump of Mount Tarawera.

The mountain's three pinnacles — Ruawahia ("split" or "cloven hole"), Wahanga ("bursting open"), and Tarawera ("burnt cliffs") were formed by the extrusion of rhyolite domes and pyroclastic debris over thousands of years. There was no oral record of volcanic eruption, but the names of its peaks suggest some dim ancestral memory. Te Arawa mythology told of an ancient and fierce cannibal spirit Tama-o-Hoi, subdued and locked in the bowels of the mountain by a tohunga or high priest of the Arawa canoe who was credited with bringing volcanic fire to the Hot Lakes District. In geological terms, the imperfectly cooled mass of lava that still lay in the heart of Mount Tarawera gave rise to the thermal wonders at its feet.

Tarawera was, and still is, considered highly tapu for the local people. The mountain's burial grounds were the final repository for the bones of their tūpuna, and only with difficulty did Europeans first obtain permission to ascend. Neither food nor tobacco was to be consumed on its slopes. While being surveyed for the Government by Stephenson Percy Smith (a pipe smoker) in 1873, the mountain was enveloped by mist. His party was forced to turn back twice before he respected the mountain's tapu by leaving his tobacco behind. On another occasion, some young local men collected the honey of wild bees on the mountain. Guide Sophia Hinerangi later recounted that all who ate it perished in the 1886 eruption, while those Tuhourangi who had refused, including herself, did not.

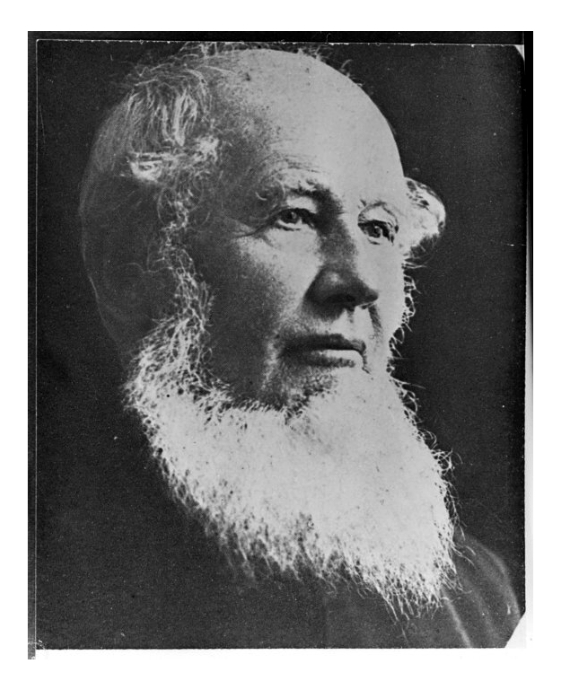

In 1843, pioneer missionary Seymour Spencer, from Mendon, Illinois, arrived in the area with his Philadelphia-born wife, Ellen. They founded first the mission station of Kariri — or "Galilee" — on Lake Tarawera, and later Te Wairoa as a “model Māori village” in a fertile valley two miles away, also by the banks of the lake. Te Wairoa would become the gateway for travellers on their way to see the Terraces.

At Te Wairoa, the Spencers established a pastoral domain of religious and economic instruction for the local Tūhourangi people. The town boasted one of the first water-powered flour mills. Its machinery and millstones were imported in 1860 to grind the wheat cultivated in Spencer's mission fields. Chief Wi Kepa converted to the Church of England and lived in the village in a European-style home.

Reverend Spencer directed the building of a chapel called Te Mu at a point overlooking the town, the lake, and the mountain. It was sawn from local mataī timber, felled, and hauled across a swamp to the shores of the lake where it was floated by raft to the Kariri headland, then overland by horse-drawn cart. Visitors to the Spencers' settlements in their heyday commented on the "neatness of the cultivation". They remarked at the "stout" fences, gates, and gravelled paths.

Among the earliest European visitors was Governor George Grey, who visited the Terraces in 1849 and was hosted by Reverend Spencer and his wife. Grey had been knighted for his services as the first governor of the colony in 1848. That same year he had assumed the office of Governor-in-Chief as part of newly established constitutional arrangements. Grey was respected by many Māori as an even-handed protector of their interests in the face of the colonial settlers, and he used his role to challenge provincial governments that clamoured for concessions of land. Yet, he was intolerant of native aspirations for political independence and governed as something of a despot.

Grey proposed to erect a hospital in the Hot Lakes District, probably at Ohinemutu due to "the efficacy of the waters for obstinate rheumatic afflictions". Reverend Spencer's wife Ellen noted the healing capacities of the local Māori were much faster than those of Europeans, and native visitors to the area sought comfort for their illnesses at Lake Rotomahana.

Grey was possibly the first, but not the last, to leave his mark on the terraces during this visit, planting his signature on the lip of one of its basins. He was known for leaving his initials — G.G. — as a message of his presence to Māori and Pākehā constituents in the areas he traveled. It is elsewhere recorded that his initials appeared "on a huge block of pumice stone standing upright on the solitary path between Rotomahana and Taupo".

In the early 1850s, the rivalry between Tūhourangi and Ngāti Rangitihi, who both laid claim to Lake Rotomahana, came to a head. Tūhourangi disputed Ngāti Rangitihi's right to offer land to a flax trader named Abraham Warbrick, who wished to set up a trading station. Warbrick was assaulted, dunked in the lake, and evicted from the land by Chief Rangiheuea's people. A challenge and a series of battles ensued.

Peace was not sealed between the two tribes until 1854, with Tūhourangi reconfirming their authority. However, Ngāti Rangitihi remained in the area. Warbrick's association also continued. He married into Ngāti Rangitihi, and his sons later pursued the tribe's claim in the Native Land Court. Their mother was Rūhia Karauna, daughter of Chief Paerau, killed in battle at Te Ariki pā in 1853. Both mother and maternal grandfather were laid to rest in burial caves on the shoulder of Wahanga Peak on Mount Tarawera.

Alfred Warbrick, the middle son, claimed to have been given his first bath in the warm water basins of the White Terraces (although evidence shows he was born many miles away). He later became known as a guide in the area, renowned for his daring deeds, and once spent twelve minutes rowing about on a geyser lakelet taking soundings, only to witness his brother Joseph perish at the very same geyser just three weeks later.

By 1859, the colonial Government was beginning to take an active interest in the geological wonders of their newly claimed domain. In that year, German-Austrian geologist Dr. Ferdinand von Hochstetter visited Rotomahana to survey its surrounds on the Government's behalf. He'd been told of its wonders by George Grey, now stationed in South Africa as Governor of Cape Colony. Hochstetter had been assigned to map the lake and the whole volcanic region, one of the few to do so before 1886. The terraces, Hochstetter reported, "baffled description".

The people of Te Wairoa were now exploiting the commercial opportunities that the terraces provided more systematically. In 1860, Lieutenant Bates described being "much impressed at the march of civilization as shown by a board which stood at the entrance to the settlement and with which large words inscribed the rates the natives required for travelling as guides to Rotomahana". Visitors remained dependent on the hospitality of local Māori until the first hotels were established in the mid-1870s.

Yet, once more, commerce was to be interrupted by war. With Grey's departure as Governor, political activism among settler communities had grown, and there was increased pressure upon Māori individuals to sell communally owned land. Disputed land sales and the fear of ever-encroaching settlement led to united Māori opposition under a new pan-tribal monarch, Tāwhiao of Tainui, the Māori King. Governor Thomas Gore Browne voiced the opinion that Māori needed "a sharp lesson". By the early 1860s, the situation had ignited into civil war. Over the next decade, government campaigns against the "Kingites" were countered by guerilla attacks from within the Waikato heartland or "King Country".

Historical enmities ensured that Te Arawa sided with the colonial Government against those rival tribes who took up the battle on the side of the Māori King. Chief Wi Kepa of Tūhourangi fought for the Kūpapa (pro-government Māori) army, where he rose to the position of major.

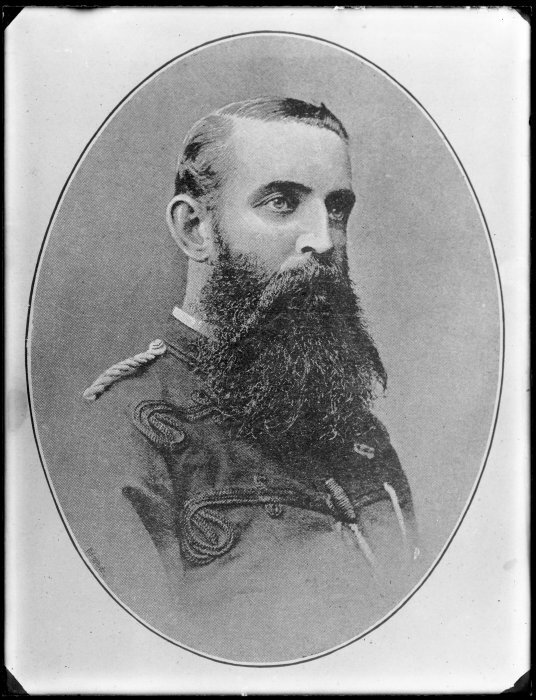

The uniform and equipment of the Arawa army were influenced by the Scottish attire of their colonial commander Gilbert Mair. The kilts of Mair's Arawa soldiers were more suited to movement through the bush than conventional garb. Warriors cut a striking figure in a red-banded cap, blue jumper, bright tartan shawl worn kilt-wise, tower percussion musket, belt, and bandolier.

At the height of the conflict, the missionary Spencer evacuated Te Wairoa with his family and settled in the coastal town of Maketū. Changed forever by the war, many Tūhourangi drifted away from the Reverend's evangelical Anglican teachings. The chapel that Spencer had built fell into disrepair, as did the flour mill.

In the midst of these skirmishes in 1870, Queen Victoria's son, Alfred, the Duke of Edinburgh, arrived "to see the wonders of the Hot Lakes District and the Rotomahana Terraces". He was escorted there by Mair's kilted Arawa brigade, under the charge of Major Frederick Gascoigne. The tapu on the water birds of Kaiwaka Stream was lifted for the royal visit, and the Duke was offered tribute by being poled by canoe up the sacred stream to the lake.

Gascoigne described the royal party: "The visitors enjoyed themselves thoroughly, swimming in the hot pools and seeing Māori war dances and hakas; and, copying my shawl costume, went about in kilts with bare legs... The Duke was well-tattooed on the arms, breast, and legs with coloured flowers, birds, and dragons, in the Japanese style, but Lord Charles Beresford was the most elaborately tattooed man I have ever seen. He had coloured designs, besides the usual nautical emblems, anchors, ships, and dolphins, all over his body. He was of medium height, very powerfully built, and of good figure. On parting, the Duke gave me a signed photograph of himself in memory of his visit and expressed himself as greatly pleased with the arrangements for his comfort, protection, and amusement." The Duke of Edinburgh left his signature elsewhere, following the example of Governor Grey and others by making his mark on the terraces themselves.

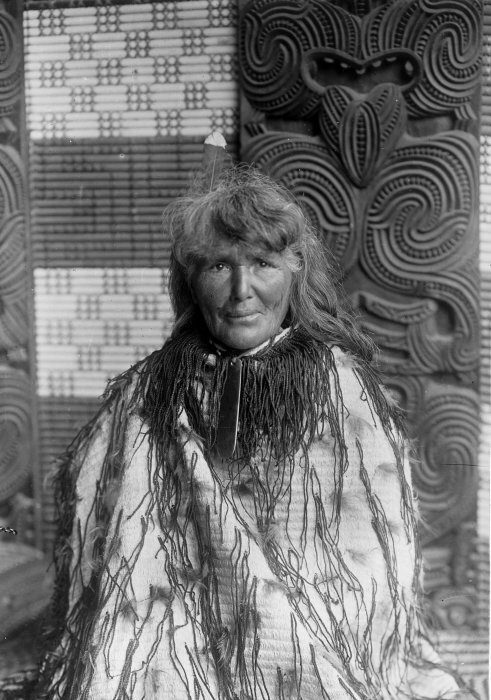

Around this time, there arrived at the terraces a middle-aged woman named Sophia Hinerangi. Originally from the far north, Sophia was to marry into the Tūhourangi and become one of Rotomahana's principal tour guides. Sophia was the daughter of a Ngāti Ruanui mother and a blacksmith father from Aberdeen. She had grown up in the Bay of Islands, where an earlier marriage was said to have born her 14 children. Her second marriage to Hori Taiāwhio, with whom she came to Te Wairoa, bore a further three.

Historian Jennifer Curnow describes Sophia: "Well-educated and bilingual, she arranged the tour parties, supplied visitors with information, settled accounts, organised the other workers and was a guide, philosopher and friend to thousands of tourists who were fortunate enough to obtain her services." Guide Sophia appeared to possess the spiritual powers of matakite, or supernatural insight. In the early 1880s, when a local stream on Tarawera rose rapidly to unprecedented heights, alarming people of the threat of flood, Sophia saw a giant ngārara, or lizard, struggling up the stream. No one else saw the creature, but many believed her.

Government land confiscations following the war were indiscriminate and often depended on the land's cultivation value. Some tribes that had sided with the Government lost large blocks, while other more bellicose tribes lost little or nothing. Native Land Courts regularly sat around the country to establish titles, but it was often merely preparation for purchase by the Crown. Māori men had had the right to vote in the governing constitution since 1867, yet large portions of the central North Island remained isolated and independent. While Chief Wi Kepa stood unsuccessfully for the Western Māori seat in the House of Representatives in 1871, 1876, and 1884, Tūhourangi still maintained firm control of their lands. With the war's end, tourism at the terraces settled into a regular pattern.

Travellers to the Terraces in the 1880s usually arrived by steamboat at Tauranga and took the bridle track inland at Maketū 70 km to Te Wairoa, stopping overnight at Ohinemutu on the shores of Lake Rotorua. By 1879, Ohinemutu boasted three hotels.

From Te Wairoa, visitors were escorted by whaleboat across Lake Tarawera to the tiny settlement of Moura, where they stopped to purchase cherries, potatoes, and koura (freshwater crayfish) for lunch, before beaching at Te Ariki, where they alighted and passed over a narrow strip of land to avoid disturbing bird life in the Kaiwaka Stream. At Rotomahana, a canoe was once more taken to reach the Terraces.

Organised guiding was a profitable profession. The boat journey to Rotomahana cost two pounds; permission to take photographs or make sketches, another five. The young men of Tūhourangi were rostered on whaleboats, up to twelve at a time, to ferry the tourists across Lake Tarawera. From guiding and boat fees alone, it is estimated that the tribe had an annual income of 6,000 pounds.

The commercial proficiency of the Tūhourangi was not welcomed by all comers. Charles Spencer, who published an illustrated guide of the area in 1885, wrote: "The natives have ceased to grind or cultivate the golden grain, preferring to cultivate the acquaintance of the Pākehā, and see what amount of gold they can grind out of him instead."

The Tūhourangi of this period were said to be so affluent that they had replaced the shells in the eyes of the carved figures on their meeting house with gold sovereigns — a story unsubstantiated by photographic evidence. In any case, the 250-odd Māori population of Te Wairoa lived well on a diet of pork, bacon, beef, bread, sugar, and butter. Families pooled money to buy alcohol for social occasions. All were purchased from a local Tūhourangi-operated store.

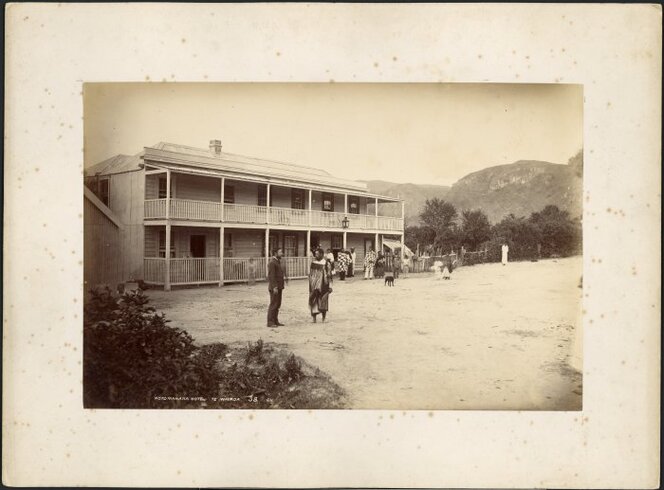

By the 1880s, Te Wairoa had two tourist hotels, the Rotomahana (formerly the Cascade Hotel), a solid two-story "well-managed hostelry" run by Joseph McRae, and the Terraces Hotel, an alcohol-free establishment run by a Mr. and Mrs. Humphreys "on temperance lines". Up the road was the Snow Temperance Hall, established in memory of a late American anti-drink crusader whose work was now carried on in the town by the local schoolmaster, Charles Hazard, and several leading men of the tribe.

In 1881, the Government passed the Thermal Springs District Act, laying claim to a portion of Sulphur Point, near Ohinemutu, as the site for a sanatorium to promote and exploit the region's thermal attractions. New roads were being carved through the area to enable better access for travelers. The number of visitors to Rotomahana doubled every few months, and plans were afoot to build a hotel adjoining the Pink Terraces.

In 1884, the artist Charles Blomfield negotiated a special fee of five guineas to paint the terraces over an extended period. On an earlier visit in 1875, the painter had encountered some hostility when he had ventured to the terraces on his own. This time, he arranged for a meeting with the affected tribal representatives to agree on a lump-sum payment beforehand. He brought with him six-year-old daughter Mary and his own boat.

The insistences of Tamihana, of the Ariki village, for further payment as a guide were doused when the authority of Wi Kepa, head chief of the district, was invoked. Tamihana was the grandson of Chief Rangiheuea. He and his young daughter, as well and his aged grandfather, who Blomfield described as "an old tattooed warrior of a hundred summers", spent time with the Blomfields, watching Charles paint, while the children skipped fearlessly among the geysers and hot basins, "making mud pies" and "hunting for petrified ferns and birds' feathers in the hot water".

Blomfield and his daughter spent six weeks at the lake, enjoying a view of the terraces that few visitors had or would experience again. He recalled, "On a moonlit night, I would take the boat, and leaving my little Mary fast asleep in the tent, pull slowly around the lake. It was a most uncanny experience, the mysterious shroud of vapour, the absolute solitude, the strange, weird sounds on every hand, hissing, gurgling, moaning, sighing seemed like some unknown world, while every few yards a wild duck would rise from the water with a startled cry, and vanish into the gloom."

He observed the tourists come and go, "every weekday, from ten to thirty of them, mostly moneyed people from all parts of the world. They would arrive at the White Terrace about 11 am, view the sights there... and have lunch at a little boiling spring where they ate potatoes and koura cooked in boiling water, cross over to the Pink Terrace, bathe there and go straight back". Blomfield noted with dismay that the locals now charged two shillings and sixpence for visitors to be canoed down the Kaiwaka hot stream back to Lake Tarawera.

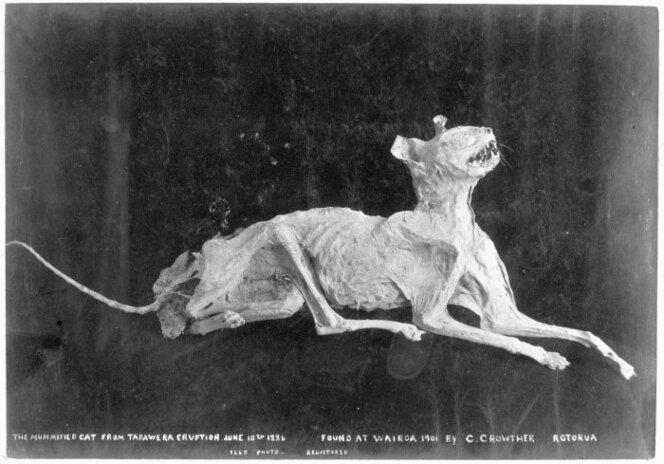

In the weeks before Mount Tarawera erupted on 10 June 1886, a series of strange events took place. A plague of sickness had besieged the Tūhourangi for several months, probably typhoid, taking the lives of many of the district’s youngest and brightest.

An old tohunga named Tuhoto Ariki became implicated in the deaths. Tuhoto was a relative of Ngāti Rangitihi guide Alfred Warbrick, said to be more than 100 years old and "a medium between the natural and the spiritual world". He was regarded with fear and awe because of the enormous power of his tapu.

Tuhoto was said to have visited friends in a village near the mountain. On his return, a previously healthy child at Te Wairoa had sickened and died. Chief Aporo Te Wharekaniwha, the guardian of the Hinemihi meeting house, confronted the old tohunga and is said to have cursed and handled him in a manner considered unwise when dealing with the tapu of a spiritual mystic. Aporo subsequently fell ill and died himself. Some say Tuhoto conjured up the ancestral spirit of the mountain in his indignation.

On the morning of 31 May, eleven days before the eruption, guide Sophia and a party of tourists arrived at the usual embarkation point on the edge of Lake Tarawera to find the creek dried up and the whaleboats stuck in the mud. As they stood there in Sophia's account, the water came up with a crying sound all along the shores of the lake, floating the boats again, then rushed away again just as quickly. The expedition proceeded when the lake level rose once more, but the guide, boatmen, and tourists were unnerved.

Aboard the boat that day were six Māori crewmen; Father Kelleher, a priest from Auckland; Dr. T. S. Ralph, from Melbourne; Mr. William Quick, also from Auckland; Mr. and Mrs. Sise, and their daughter from Dunedin; and three unnamed local Māori women, “one of whom was the dead chief’s sister, returning from her brother's tangi”, as Mrs. Sise wrote in a letter to her son. It was Chief Aporo's whaleboat. As it pulled out from the inlet, the chief’s horse was spotted on one of the nearby hills, a sign that the Māori people present interpreted as an omen.

Louise Sise’s account continued: "After sailing for some time, we saw in the distance a large boat, looking glorious in the mist and sunlight. It was full of Māoris, some standing up, and it was near enough to see the sun glittering on their panels. The boat was hailed but returned no answer. We thought so little of it at the time that Dr. Ralph did not even turn to look at the canoe, and until our return to Wairoa in the evening, we never gave it another thought. Then to our surprise, we found the Māoris in great excitement and heard from McRae and other Europeans that no such boat had ever been on the lake."

William Quick later confirmed to Alfred Warbrick that such a canoe had come "about half a mile from us and then it disappeared. It was to all appearances a war canoe of olden time, with a crew of paddlers," he recounted. "It had the projecting bow piece and the high sternpost that were fitted in large canoes of the waka taua or war canoe type."

Another boat on the lake that morning also confirmed the sighting of a vessel with the appearance of a war canoe. Josiah Martin, one of the passengers, sketched what he saw, although the drawing is now lost. Father Kelleher also sketched the canoe, from which a painting was later made.

The strangest account is that of Guide Sophia: "We thought it was someone going to catch kouras... but as we looked, the canoe got larger and shot out into the lake, and then from one man the number increased to five. They were all paddling fast, but to our horror, they appeared to have dogs' heads on the bodies of men. Then the canoe got larger still. It looked like a war canoe, and then we saw 13 in it, all paddling faster and faster. Whilst we were watching, astonished and terrified (for the boatmen had stopped rowing), the canoe got smaller and then, with the last remaining man, disappeared into the waters of the lake."

In a separate account, she said: "We had not gone very far over the lake when we saw another canoe in the distance being vigorously paddled but never moving. Several said they could see it, but as I looked earnestly, the men who paddled changed to dogs, and then the whole thing vanished."

When reported to Chief Rangiheuea, who was wintering over at Puai Island, the old chief is described as replying: "If that is true, there is going to be a big war and many chiefs and people will be killed."

Back at Te Wairoa, people were told of the waka wairua or phantom canoe. Tuhoto, the tohunga, declared the vision to be an omen: "It is a sign and a warning that all this region will be overwhelmed," Alfred Warbrick records him as saying.

At the terraces that day and again the following week, Sophia noted unusual thermal activity. On her last visit on 7 June, she described the unusually high level of the lake. She recorded seeing the geyser Whatapoho (a pain in the stomach) sending out flames and smoke. "I think this is my last day at Lake Rotomahana," she is reported as saying.

The evening of 9 June 1886 was clear enough in Te Wairoa for Charles Hazard and two visiting surveyors to engage in amateur stargazing. They watched the occultation of the planet Mars — whereby Mars was eclipsed by the moon. They retired at 11 pm.

Alfred Warbrick was in the area that night, out shooting pigeons in the Makatiti forest. He was awaiting his family's title to come again before the Native Land Court, then sitting at Tāheke.

Chief Rangiheuea was spending the night on Puai Island in the middle of Lake Rotomahana with ten others, laid on the hot earth to keep out the cold and rheumatism.

At Te Wairoa, Sophia and her family were asleep in their home, a long narrow whare with an unusually steep-pitched roof.

The tohunga Tuhoto lay in his small whare nearby, apparently sleeping also. But some say he was chanting karakia to unleash the punishing spirits of his ancestors.

Just after midnight, all were awoken by a prolonged and increasing series of booming earthquakes that could be felt as far away as the Bay of Plenty coast.

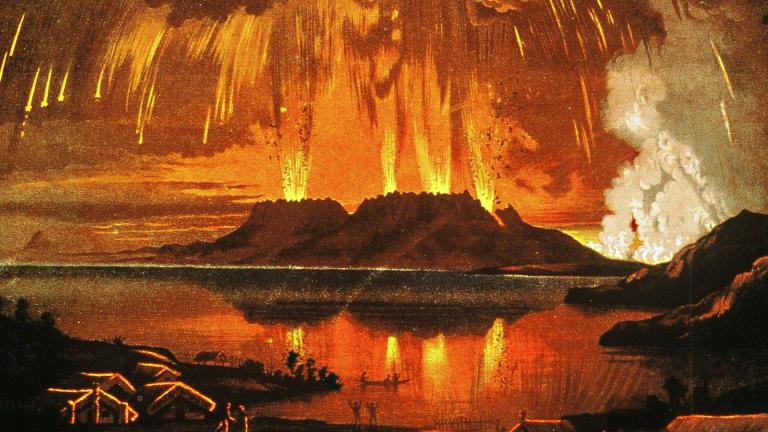

The eruption began at the Wahanga dome at 1:30 am. Those that had been shaken from their beds witnessed a rising black cloud above the mountain, cut by lightning and expelling electrical balls of fire. A violent earthquake at 2:10 immediately preceded an eruption column which rose over nine kilometers above the mountain, followed at 2:30 by basalt scoria eruptions that ripped a fissure down the length of the mountain with a noise described by those as far away as the coast at Maketū "as if all creation was being blown up". Witnesses saw seven or more distinct columns of fire spread out into black clouds that glowed red from the reflection of the fiery pits below.

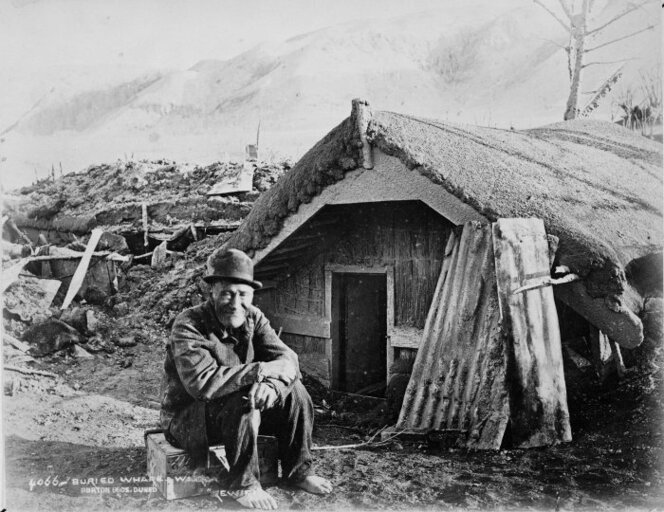

At 3.30, eruptions at Lake Rotomahana uncapped the large geothermal system in that area. The release of pressure allowed its waters to flash into steam, causing high-speed blasts of hot rock that swept horizontally outwards for ten kilometers from the lake, pulverizing the village of Te Ariki. At the same time, cold mud rained vertically out of the eruption cloud to bury Te Wairoa and the surrounding countryside as far as Ohinemutu. Thick volcanic ash spread for many miles further.

Sophia Hinerangi's solid steep-roofed whare proved a safe haven in the storm of rocks and mud that followed. Many of the townspeople gathered there for the night, once the roofs of every other building in the town, including the hotels, had collapsed beneath the weight of mud and ash. Sophia later claimed that her whare had been "tapued ".

More than 150 people were killed and buried in the violent events of that night. The eruption was all but over by 5:30 in the morning, although dawn did not break until well into the afternoon. The devastation it revealed was unprecedented.

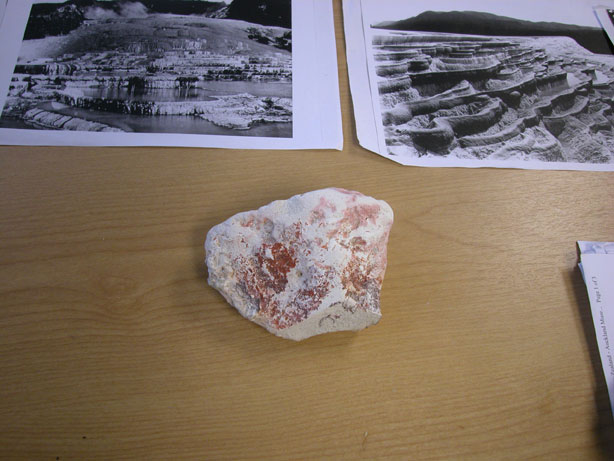

Geologists describe Tarawera's eruption as "unusual on a world scale". Surveyor S. Percy Smith found that the new level of what was once Lake Rotomahana was 250 feet lower than the former lake bed. The whole and its surroundings had been scooped out, leaving in its place a line of craters, mud geysers, and fumaroles.

Alf Warbrick and former Te Arawa commander Captain Gilbert Mair, now a judge of the Native Land Court, were among those who explored Tarawera to discover the terrain so vastly changed. Where the lakeside settlement of Moura once stood, a layer of mud seventy-five feet thick had blotted out the houses and the 39 people who lived in them. A large grove of karaka trees that had marked the village site was seen floating a mile out in Lake Tarawera. At the place where Te Ariki stood, houses and people were buried beneath 250 feet of mud. The tall, dense Tikitapu bush had been stripped and flattened as if by gale-force winds.

Alf Warbrick hauled a whaleboat across the devastated terrain from Rotorua. He lowered it 250 feet onto lake Tarawera to survey the damage. In his recovery expeditions, he unearthed the whare of his old relative Tuhoto, who emerged shaken but alive after four days of burial. Despite his protests, Tuhoto was removed from his dwelling. His long hair was cut, and he was taken to the sanatorium at Rotorua, where he died two weeks later.

Warbrick never accepted that the terraces had been completely destroyed. In the years that followed, he initiated a public debate about their fate and spearheaded calls to "uncover the terraces". But the terraces had been vapourized. In the next seven years, Lake Rotomahana refilled naturally with spring water to several times its original breadth and depth.

Warbrick went on to become the accepted guide for visitors eager to view the "post-eruption wonderland". In 1903, the Department of Tourist and Health Resorts inaugurated a “Round Trip” tourist excursion traversing the scene of the eruption, with Warbrick as their guide.

Sophia Hinerangi continued her guiding career at Whakarewarewa Thermal Reserve, near the new government-developed tourism town of Rotorua. In later years, she encouraged younger women to take up tour guiding, which remained a lucrative form of employment for the now-exiled Tuhourangi people. She died at Whakarewarewa in 1911.

The painted meeting house Hinemihi, which had sheltered many from the deluge on that tumultuous night in 1886, was excavated from the volcanic ash and mud and exported to Britain in 1893, where it sits to this day in the manicured gardens of Clandon House in Surrey.

Over the following century, New Zealand tourism grew to become the country's single biggest source of foreign earnings.