In communicating with Carolee Schneemann in the last months of her life, there was a sense that the artist was in a race against time. Schneemann — now regarded as one of the most important artists of the 20th century — knew that death was approaching, and there was still so much to clear up, articulate, and preserve. In the last years before her passing in 2019, Schneemann had finally overcome decades of rejection and neglect of her work to receive the art world’s recognition and adulation in its fullness. There were major retrospectives at the Museum der Moderne Salzburg, the Museum für Moderne Kunst in Frankfurt, and MoMA Ps1 in New York. In 2017, Schneemann received the Golden Lion award for lifetime achievement at the Venice Biennale. And yet, it wasn’t always easy for the artist to enjoy this newfound respect. The path had been hard.

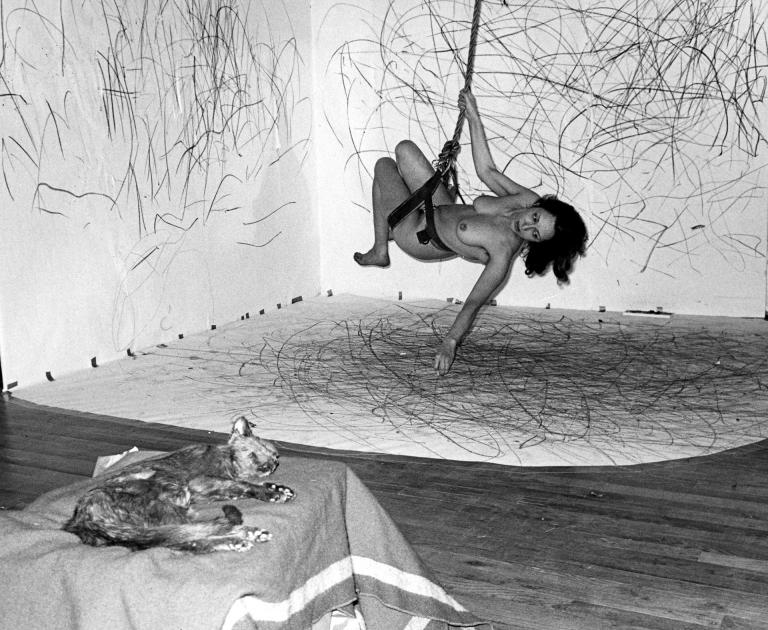

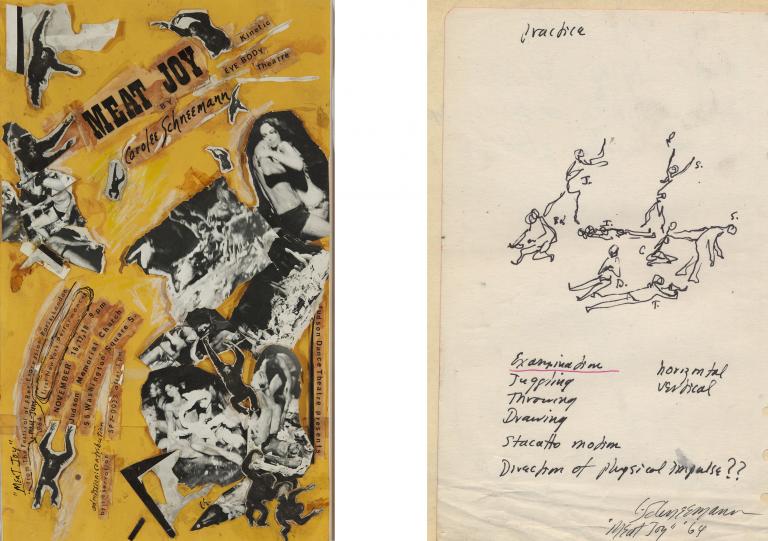

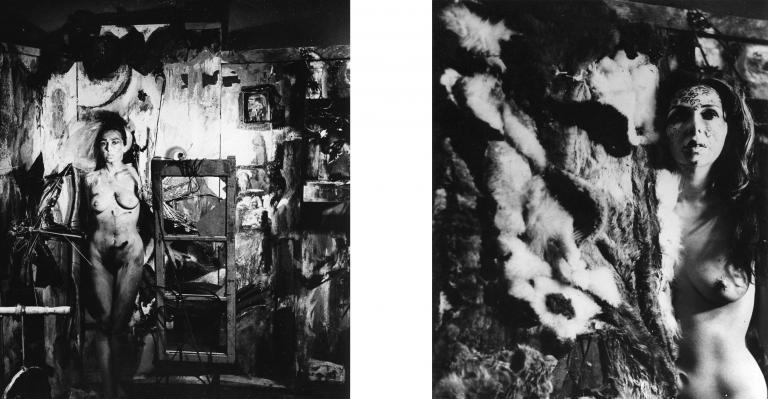

Schneemann began as an expressionist painter in the 1950s, and she considered all her subsequent work — encompassing a range of media including photography, video, performance, film, sculpture, and installation — to be an extension of the principles of painting. But in New York of the late ‘50s and early ‘60s, where the male Abstract Expressionists reigned supreme, Schneemann’s paintings were rejected out of hand. Instead, she gained fame and notoriety with her seminal performance work “Meat Joy” (1964), an erotic rite featuring a writhing assemblage of half-naked bodies, mackerel, sausages, raw chicken, and wet paint. Schneemann described the work as “kinetic theater”. Here was the “action” of Action Painting liberated into three-dimensional lived space. The work was taboo-shattering, and responses were strong. A male audience member of the debut Paris performance at the Festival de la Libre Expression emerged from the crowd and attempted to strangle the artist. Other works, including “Interior Scroll” (1975) — in which the artist, naked, unfurled, and read a feminist scroll from her vagina — would cement Schneemann in the histories of feminist and performance art.

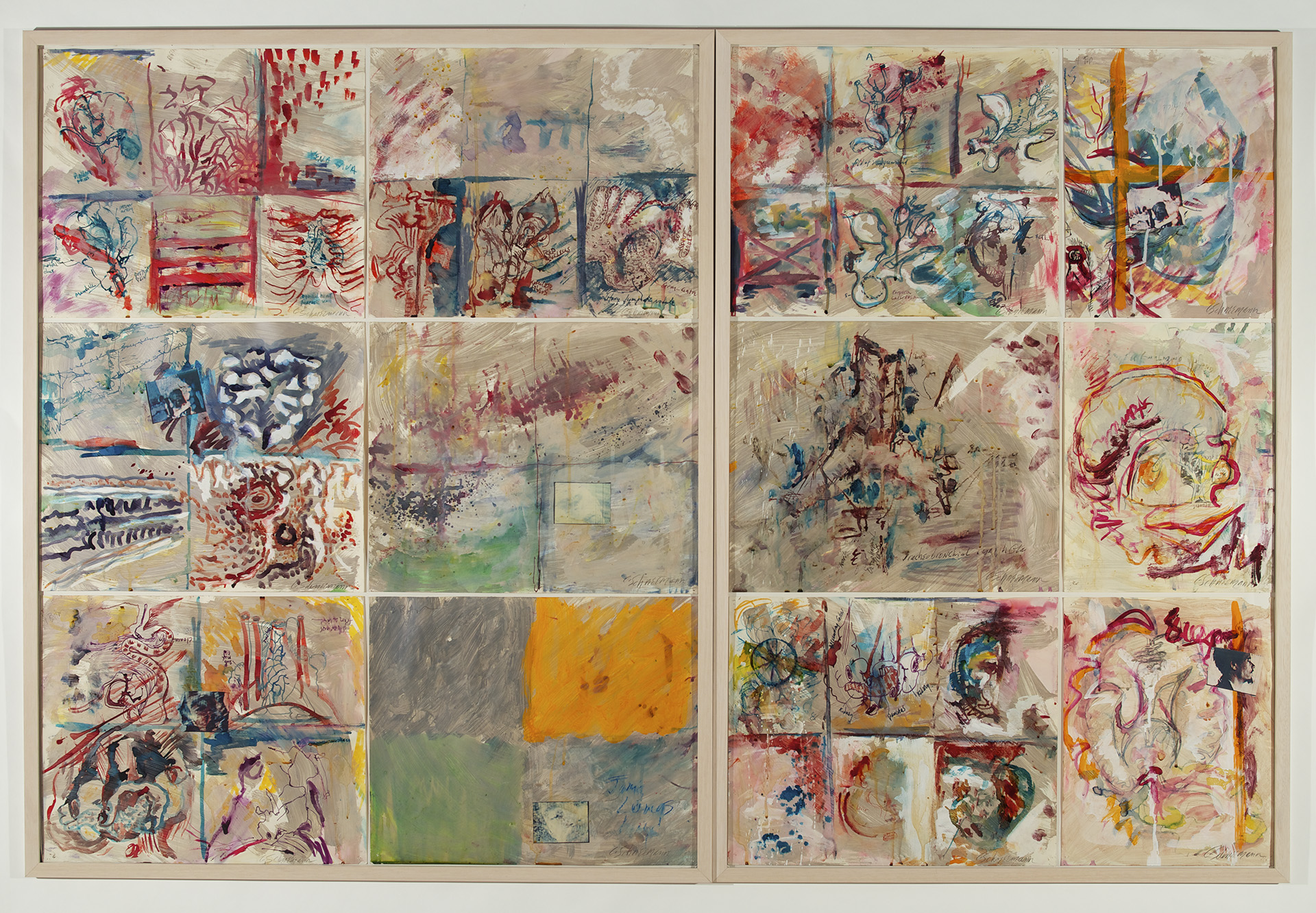

But there was so much more. And there were so many other ways of interpreting her work. The MoMA Ps1 retrospective Carolee Schneemann: Kinetic Painting (2017-2018) contained 300 such works. In the retrospectives, the paintings were finally center stage. Six decades of unwavering artistic intensity came flooding into view. This was a universe of creativity: propulsive explorations of love, pleasure, and anguish, interspecies relationships, dream visions, war, and death. The unrestrained sensuousness of the work was nonetheless connected by compositional and aesthetic rigor, as encounters enacted via no-half measures.

I spoke with Schneemann in July of 2018 in what would become a 54-page interview in the 16th issue of White Fungus. In her typical prosaic lucidity, Schneemann delved deep into her past to discuss topics such as her family, adolescent adventures in Mexico, New York’s downtown avant-garde, her unusual relationship with Joseph Cornell, and her complicated friendship with Stan Brakhage. She discussed approaching death, the toxic political climate of the US, and her desire to save her 1750 historic house. The following is an extended excerpt from the interview and begins with Schneemann talking about her time in New York in the late 1950s.

Ron Hanson: Entering New York in the late 1950s, Abstract Expressionism still held sway. There were very few women allowed into those circles and the other art circles. And you had quite a blunt expression, which you used to describe that sanctioned role, which was the “cunt mascot”. I was particularly struck by your story of the artist Marisol Escobar wearing a mask. She’s wearing a mask amongst these guys but not speaking.

Carolee Schneemann: It was at the Artists’ Club. The Artists’ Club was really the big deal — macho, important male second-generation Expressionists. And all of them had really solid, significant reputations. There was rarely ever a woman that was part of the Artists’ Club. And Marisol was there on this panel wearing a mask, and I was very certain that the only way a woman could ever really manage inclusion was to be completely masked. She never spoke at all.

RH: Did you approach her? Did you try communicating with her yourself?

CS: I loved her. But I watched her. I watched her in New York; I watched her in Venice, wherever I would be where she was. She was always so utterly composed. She’s upper-class but behaves like a mystical native. She’s like a jungle presence. She can be in the middle of everything swirling around her, and she’s utterly composed. I did see her making love on a pile of coats in a loft one night at a party. That’s my girl. She’s not so quiet now. But she was one of the few achieved present women artists whose work was being shown. She had a gallery and collectors. And then it would disappear and fade away.

RH: Were there other women in New York at that time whose work you were following or tracking?

CS: I probably told you I was spying on the women artists, but they are all consolidated with important men. So there’s Helen Frankenthaler — that’s really important work, but it’s not given the full appreciation, the strength of recognition that the men get — but she’s with Robert Motherwell. Joan Mitchell — I love that work. That’s a huge influence on me. And she’s with Barney Rosset, the publisher of the Evergreen Review, and so his configuration fights for her position. That work has sustained itself incredibly; it’s regenerative in its power, right now, especially. And then there was an artist named George Hartigan. I found out that her name is actually Grace Hartigan, but she uses another name, so you don’t know it’s a woman right away. And a few others, but they’re all configured with more important men that seem to have a way to help them.

RH: So that was an established path if you were a woman artist. But obviously, that wasn’t going to appeal to you.

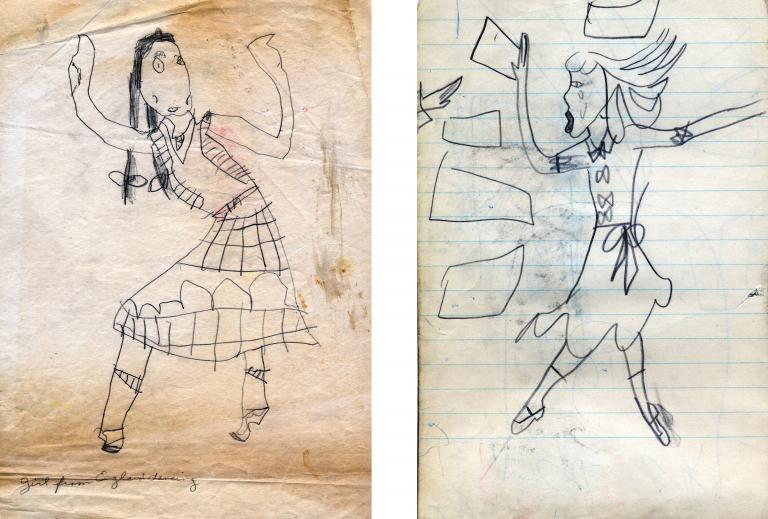

CS: Well, I had to try and figure out what’s going on. It didn’t matter if anything appealed to me or not. I’m desperately looking at art history; I’m writing my early version of “Missing Precedents”. I might be impossible and an anomaly, but I’m just going to keep doing this. And the wonderful thing about my retrospective is that it has a lot of my childhood drawings in it.

RH: I’ve enjoyed seeing those. It wasn’t long ago that you discovered them. Your mother had put them away in a box, is that right?

CS: And the contradiction is that the last thing on earth my mom really wanted was for me to grow up to be an artist — so this mixed message, then, that she did value these old things, because her writing is on a lot of them, describing them.

RH: There must be something about your mother... It’s special that she did put those aside. Maybe it was just an intuition.

CS: No, it was a real appreciation, but then she couldn’t stand for me to have a life that was different from hers — that I wasn’t just going to take care of babies and a husband and cook and clean and stay home. I mean, I ran away when I was fifteen.

RH: Fifteen years old?

CS: Yes, I had to get out of there.

RH: Where did you go?

CS: Somehow, in those days, you could hitchhike and not always get raped. I would hitchhike off to where I knew a kid from high school who had a shack in Maine or anywhere that I could get to. And then, actually, I got to Mexico.

RH: Yes. I didn’t know about this.

CS: It was in la Calle de los Indios. How’s your Spanish?

RH: Nonexistent.

CS: The Street of the Indians. And middle-class people didn’t live there. But this middle-class family, or upper-class family, had lost everything, and they were upstairs in a large, long, rangy apartment house on the Street of the Indians.

There were three sisters and two brothers, and an old man and an old woman, and I was completely bewildered because there was a cook. And I was very slow to figure out that this family had had a lot of money in Madrid, from their factory of yarns and weaving machines. The father went to Mexico to expand his business, and he lost everything, somehow. So suddenly, this rich family was very poor.

It was like being in a Lorca drama. The mother in her black dresses served dishes of food, which had been cooked in the kitchen with the maid, and she’d go first to the end of the table where the old man was, and she would yell, “¿Qué parte quieres?”

And he would pick something and take it. But they never talked to him. I didn’t know who he was. He had muddy boots in the bathroom, and the bathroom was strange because it had two kinds of toilets: one you could pee in and one that I didn’t know what it was for. It was a bidet, but he had muddy boots in there. He had become a farmer, this entrepreneur from Spain, and he was a sweetheart. But no one introduced me to him. He was in disgrace; he had lost the family fortune.

The three sisters were sitting in the backroom sewing all the time. And I was painting on my tile windowsill and being serenaded by young guys with guitars downstairs. Why was I thinking of this? It was escaping my family...

It was very nicely organized through the international group. Then I got appendicitis, and I was in the hospital. That was scary because these nuns came with their razors to shave my little pussy, on which I was just getting hair. It was terrifying.

RH: Was this your first time encountering people from a culture outside of the US?

CS: Yes, it enlightened me. It was magical. And I got to hang out in the town with other kids, you know, 15-year-olds; you always find each other at the swimming pool, at the library, at the church. Puebla, where I was, had 360 churches — one for every day of the year. So I was in church a lot, and it was all enriching for me. And when I come home, my mom is, as usual, just beside herself with anxiety and upset. My dad’s very pleased. I have different hair; all rolled up. I have pierced ears. I don’t have my appendix. I speak Spanish. They haven’t a clue what to do with me.

RH: What about your siblings? Was there a rebellious streak in them?

CS: No, nope... Well, yes, a little. My younger sister was failing English in high school, and she’s a tall, beautiful, blue-eyed blonde. She got on the train and went to New York City all on her own and went to Eileen Ford, the biggest modeling agency, and walked in there without any preamble and said that she wanted to be a model. And they looked at her and said, “Walk around a little.”

And they said, “Do you have a place to stay here in New York?”

And she said, “No.”

And they said, “Well, we have an apartment that our girls can use. We’d like you to stay there and try working with us tomorrow.”

RH: I haven’t heard much mention of your family after you became an artist. Did you keep in contact with them when you were in New York and starting out?

CS: No, I kept them away from my work. And I changed my name. I did everything I could to shield them.

RH: Is that partly why you changed your name?

CS: Partly. But also, I wanted a big, painterly, heavy name. And I was only 18 when I did that. Now I wouldn’t pick that.

RH: You would have stuck with your original name if you were doing it now?

CS: Yes.

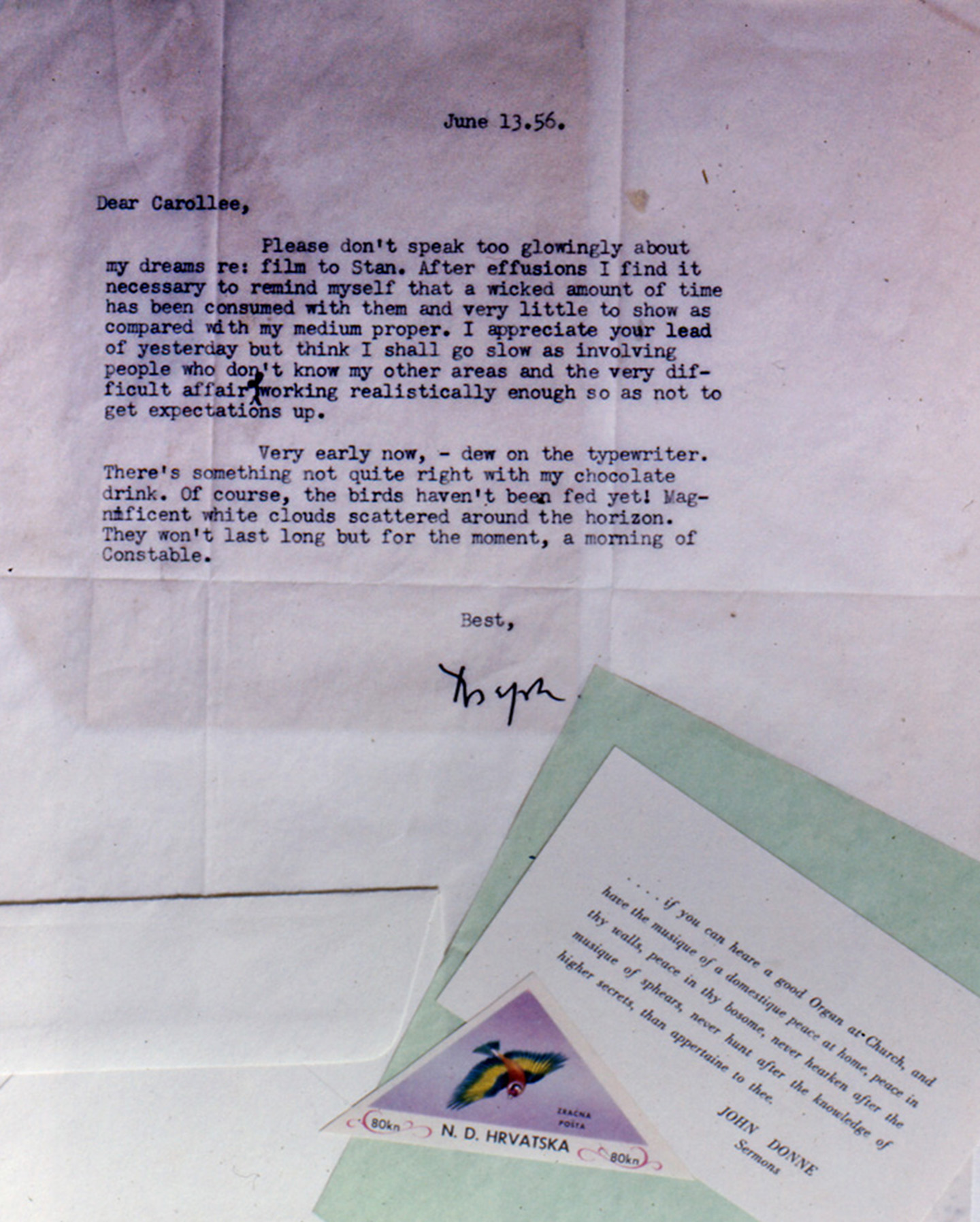

RH: When you go to New York, it starts a series of incredible events. I really enjoyed watching your interview with the curator Jasper Sharp, discussing your experience of being, I guess, a quasi assistant to Joseph Cornell.

CS: Everyone exaggerates that; everyone wants to believe that. I was just a little muse who went there rarely. But we had a friendship, mostly over the phone, because it was very difficult for Joseph to have a plan to travel, to leave home. It was mystical; it was magical.

I was only out there three times at his house, and I was one of the young women, the fantasy figures, who stayed to do work. He didn’t want me to do that. When I started to work there, he wanted me to sort like a hundred newspapers, and inside those pages, I found a drawing from Rauschenberg signed, “To Joseph, with great admiration.”

And I said, “Look what I found.”

And he said, “Put that away; I don’t want to see that thing.”

So that kept happening. He was very fragile in terms of the energies that he could have moving near him. Mostly it had to do with weather, stars, what he was reading, certain kinds of music — and then his fantasy that we would draw each other nude. And his fantasies were so intense; it was hard for me to believe that that didn’t happen. But I think he did manage to come to the 29th Street studio once.

RH: When Sharp discussed this with you, he asked if you felt threatened or intimidated by Cornell, and your answer was that you had to be careful not to threaten him; he was so fragile in terms of his relationships with women.

CS: I couldn’t tell him what I was really doing. I was creating “Eye Body” at that time. And then “Meat Joy” evolved outside of our friendship because I knew it would be too disturbing for him. He was very fearful of sexuality. And, as you know, I wrote about how much he loved his brother, Robert, the devotion to him, and the importance of that connection. And I thought that in some deep way, well — what do you call someone who loves dead bodies? What’s that called?

RH: A necrophiliac? In a sexual sense or another sense?

CS: You can love them through space, not that you really touch them. It’s necrophilia, a mystical necrophilia. But the female has to be in little slippers, in a mullet skirt, and very young and innocent and subject to responding to pieces of candy or little rainbows he would make. And his mom was a great big, noisy figure, leaning out the window saying, [speaks in a gruff voice] “Joseph, I made cakes for you and your little friend.” He was emaciated, and so was Robert, his brother — they never ate hardly anything.

RH: Thinking of you arriving with those paintings in New York, it’s fascinating. Because when I think about the Abstract Expressionists, I think of them as being the ultimate macho guys. They’re real hard-drinking, smoking... What was that experience like turning up in New York and entering that world?

CS: It was beautiful. It was such a great feeling — smoking Lucky Strike and putting white lead on my canvases, already toxic and poisonous. It’s where I want to be. And everybody says, “This is crap,” or “You’re painting like a girl.”

When I first did “Eye Body”, as you know, they said, “Put your clothes on if you think you’re going to paint,” and “This doesn’t make sense, these photographs.” So I’m so used to rejection that the recent acceptance has got me very bewildered, and I can’t work.

RH: Did you interact with any of those Abstract Expressionists?

CS: Well, I meet them; it’s not quite like interacting. I’m always a kid, and I’m always a girl, or I’m always this sexy figure. So I have James Tenney, my bedrock, my partner, my confirmation of love, sexuality, and work. And I’m also being hugely influenced by the music he’s practicing; I heard Ives through our little wall day and night. Tenney is not a swift learner, so I hear the same chords being practiced, and it’s very influential on my sense of fracture, repetition, breaking form apart, giving it distance to reoccur, come back.

And, you know, we’re studying culture together. We have a few friends; that’s it. And Stan Brakhage is one of them. We share everything with Stan, except that he does not accept, or he can’t accept... He thinks I’m a monster.

RH: Why did he think of you as a monster?

CS: Because a normal female is going to adore her partner and have babies and live in his dynamic without a strong self-definition as something more than a wife. Tenney and Brakhage are best friends from high school, so the envy and possessiveness of Stan towards Jim and his fascination with and envy of our relationship is very complicated.

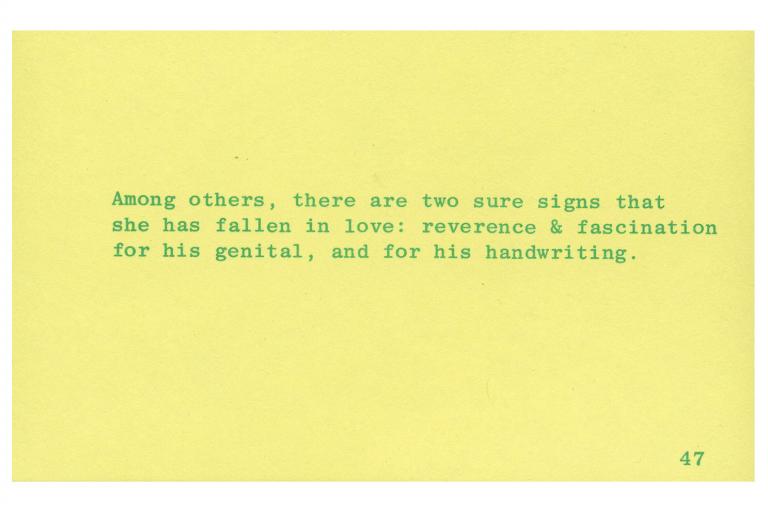

RH: What was it about your relationship that he was envious of?

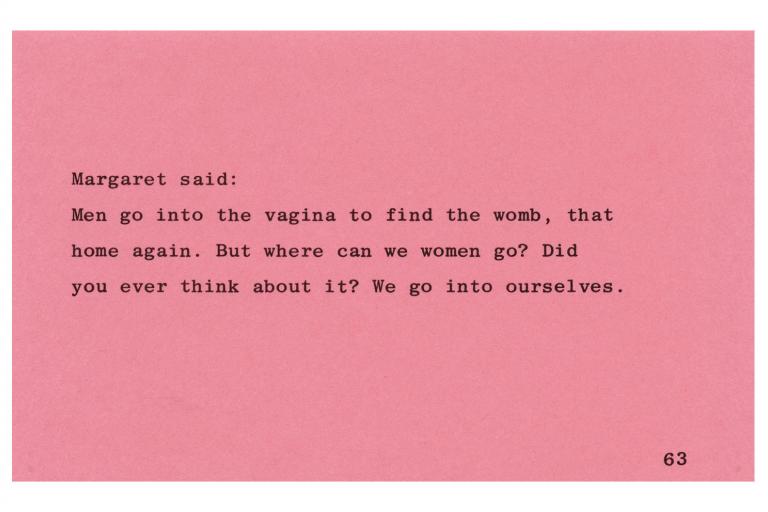

CS: He recognizes that it’s passionate, and it’s sexually ebullient and flourishing. So he wants that, but he doesn’t want to have... When he meets Jane [Wodening], his life partner, for 35 years, he has her burn all of her things on the side of the mountain where they lived: her diaries, her paintings, her clothes, her books. Everything is set on fire. And then she has a handmade dress that she wears as his bride. So her life is consecrated to him.

After five children and all the creative work together, Stan says, “I don’t want to live with you anymore; I’m changing my life.” So I’m reading a lot of her writing because she’s an amazing writer, a profound naturalist. And she moves into her old car and drives across the country for two years.

That’s a pattern that we’ve discovered for women whose marriages are solid and coherent, and consistent. When their marriages are suddenly blown apart by the male partner, they often start driving. They don’t know who they are; they don’t know where they want to be.

RH: It must be strange for you because you’re reaching this incredible moment, personally, with your work, which you’ve strived for. But it must be bitter-sweet, given the broader context of where the country is at.

CS: Well, it’s worse than bitter-sweet now because it’s a huge undertow. It’s like a tsunami, slow, slow, slow, that can destroy and eviscerate anything that is at all fragile or sensitive, thoughtful, natural — because this government really likes to create disaster and pain.

RH: Where things have headed can’t be a total surprise to you, given how tuned in you’ve been to events.

CS: Oh, we’re surprised. We’re surprised. It’s worse than we thought it would be. There’s a cultural shock that we can’t really absorb. In the 60s, there was such a powerful coalition of resistance. It was very strong. It was huge. We don’t see that now; it’s fractured. The degree of destruction and declivity, it goes from the cradle of civilization right to your backyard. Well, not quite our backyard, because we live in paradise right here, in this part of New York state. You go further north, and people are hungry and broken and desperate. But right around here, this is happy, delusionary, a wonderful place to be. But there’s no assurance or confidence to maintain it. I mean, I’ll be gone, and I won’t know what happened. So it’s very annoying.

RH: You don’t think it’s fortunate timing?

CS: The only fortunate timing is that the Catholic graveyard on Springtown Road, the road where I’ve driven past for 50 years, has now opened a green section. And a highly political activist friend of mine has been buried there, in a shroud, in a wooden box under the trees. So I think that’s wonderful because I’d like to be buried on my land right here, but there are lots of rules and laws. You can’t be near your border or this or that, but I could be just up the road.

RH: You’ve been so focused on creating your work and stubbornly ensuring that it gains a reception.

CS: You can’t ensure that.

RH: But you’ve forced the issue. You haven’t allowed it just to be forgotten, and you’ve persisted to the point where now there’s a lot of people invested in it. I’m not talking financially, but invested in it intellectually, artistically, in terms of scholarship. So what is your goal now? What do you want to do next?

CS: I want to save the house, this 1750 historic house. My galleries are not willing to commit to saving the house. They may want to work with the objects, the film, the drawings, the paintings, but they won’t do an inventory! So right now I have to hire, at my own fragile expense, someone to do an inventory to know what’s here. It’s never been done; it’s bewildering not to have done that. It’s up to me and my assistant Lilah. We have to figure all this out, and she works here four days a week from ten to five. And it’s just vast.

You know, I’m kind of drowning in all the work I’ve already done, and I’m writing now. I’m writing a lot because I can’t be building, and I can’t find my cameras. And I have to go to different doctors at least a third of my time, and it’s costly. I have to do alternative therapy, which may be helpful, procedures that are not covered by health insurance or are only covered partially. So that’s a drain on finances. And then I have to provide for just maintaining the home and doing everything that it requires before it gets left to my foundation. We’re maintaining a foundation, but it doesn’t have much money.

RH: I’m sorry to hear about the health problems, but you haven’t lost any mental sharpness.

CS: No, that’s fine; I’m lucky. I have a lot of friends who have lost that.

RH: Maybe it’s partly that you’ve been so active. You haven’t allowed your mind to slip.

CS: No, Ron, it’s not what you allow; it’s a crapshoot. It’s just kind of what you inherit. I mean, there are things that you really can’t shape or control. I can’t control the degeneration of my arteries. I absolutely can’t control the arthritis. The doctors think they control it, but they don’t. So it’s a whole complex puzzle, which only leads to your being dead! And you better clear everything up along the way, as much as you can. So we’re all very busy, my generation; if we’re functioning, we’re frantic with stuff to do. And then, most of all, I need to sit on the porch and study the wind and the leaves.

RH: At least you’ve got clarity. You know what you’re doing.

CS: It’s beautiful here, and I have a great cat, La Niña. She is astonishingly brilliant, thoughtful, moving, and interpolates complex circumstances. I’ll tell you about one cat event. I had a vein break in my leg; it was bleeding all over. It was just like something that sprouted without my feeling it. I was with a friend, and he got me inside on the bed. La Niña runs to my leg, hissing, and faces my friend [makes cat hissing sound effect]. And she said to him, “Did you do this? Did you do this?”

I said, “No, no, no. It’s OK. He’s taking care of us.”

And this cat understands everything, and she turns to the blood on my leg because she knows. She’s a hunter, and when she brings in something that is what we call “bleeding”, it’s going to “croak”. And so when she saw this blood, she thinks it’s going to make me not move anymore, and I’ll be gone like the things she kills — first they bleed. So this cat, she never leaves my leg until the blood stops, and she just stays by my leg for about five hours. So this is one of her remarkable behaviors. Most cats aren’t that insightful.

RH: You mentioned that in the reception of your work that there are still frustrations. What are some areas that you think have been overlooked at this point?

CS: Well, you know, I can’t think about it very much; it’s daunting. I need a tremendous amount of assistance to sort everything out and just see if these values can be sustained or maintained. Or will the mice continue to chew up the prints? Will the raccoons get into the costume drawer again? Will the birds keep stealing parts of my constructions because they need bits of silk fabric? There’s so many odd elements here. There’s all the videotapes that need to be edited and made available, the lectures or things that could be useful. But I can’t do all that. I try to organize or delineate it, but then I have to make some work. And the work I’m doing now is writing — because that seems to be what’s possible, and it emerges. I’m in a kind of writing trance that happens.

RH: What kind of things are you writing?

CS: I’m writing a lot about the body and death, and the physical disasters we survive... Autumn frost influenced my writing this morning. My memory wanders around freely, so I can enter and exit all kinds of lost sensations very quickly and intensely. I can be at the beach when I’m seven years old, in my little yellow bathing suit that has rumples on it, and in my sandbox digging up little tiny clams. I can go there and smell the sea. It’s a wonderful, old wooden aroma in buildings near the ocean.