Histories

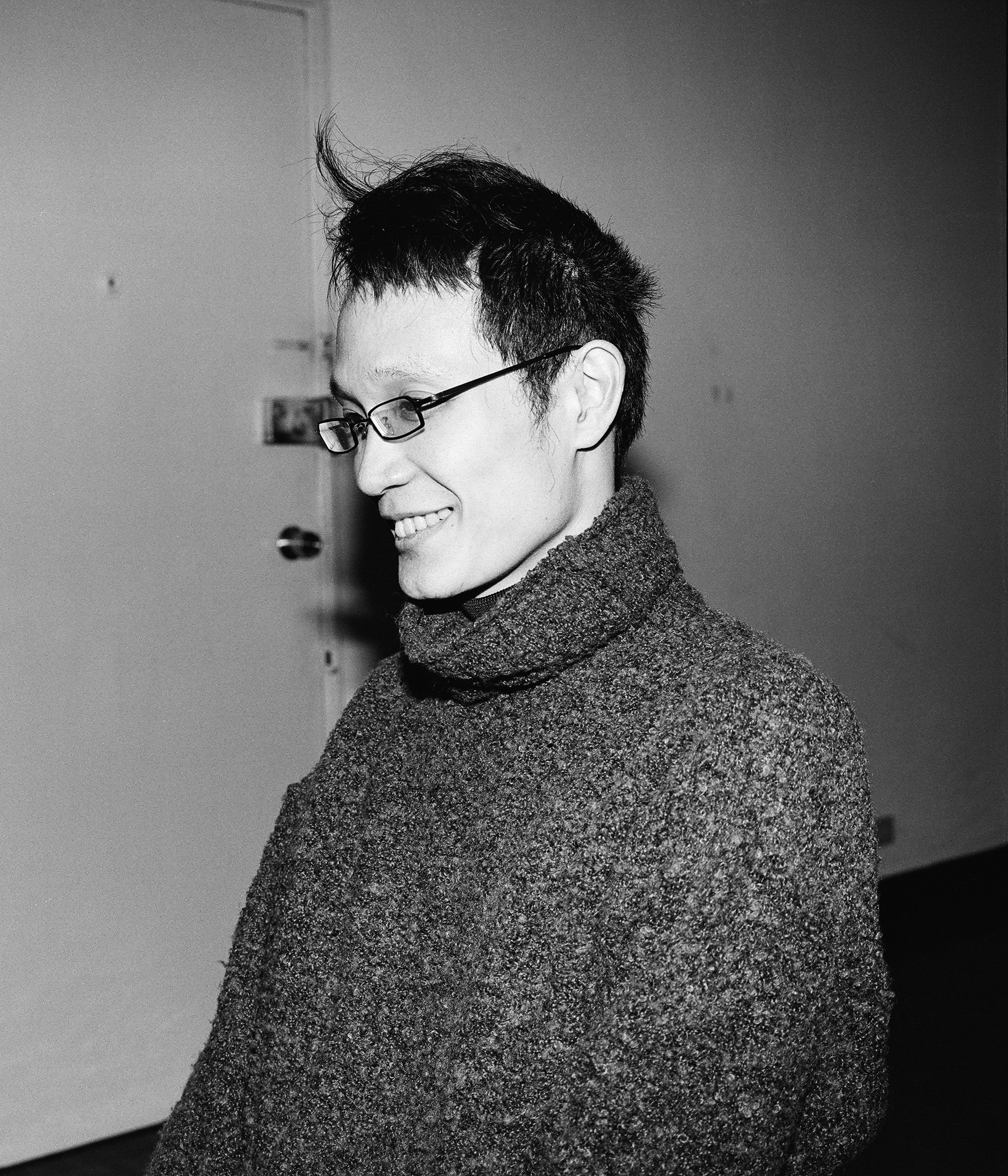

林其蔚

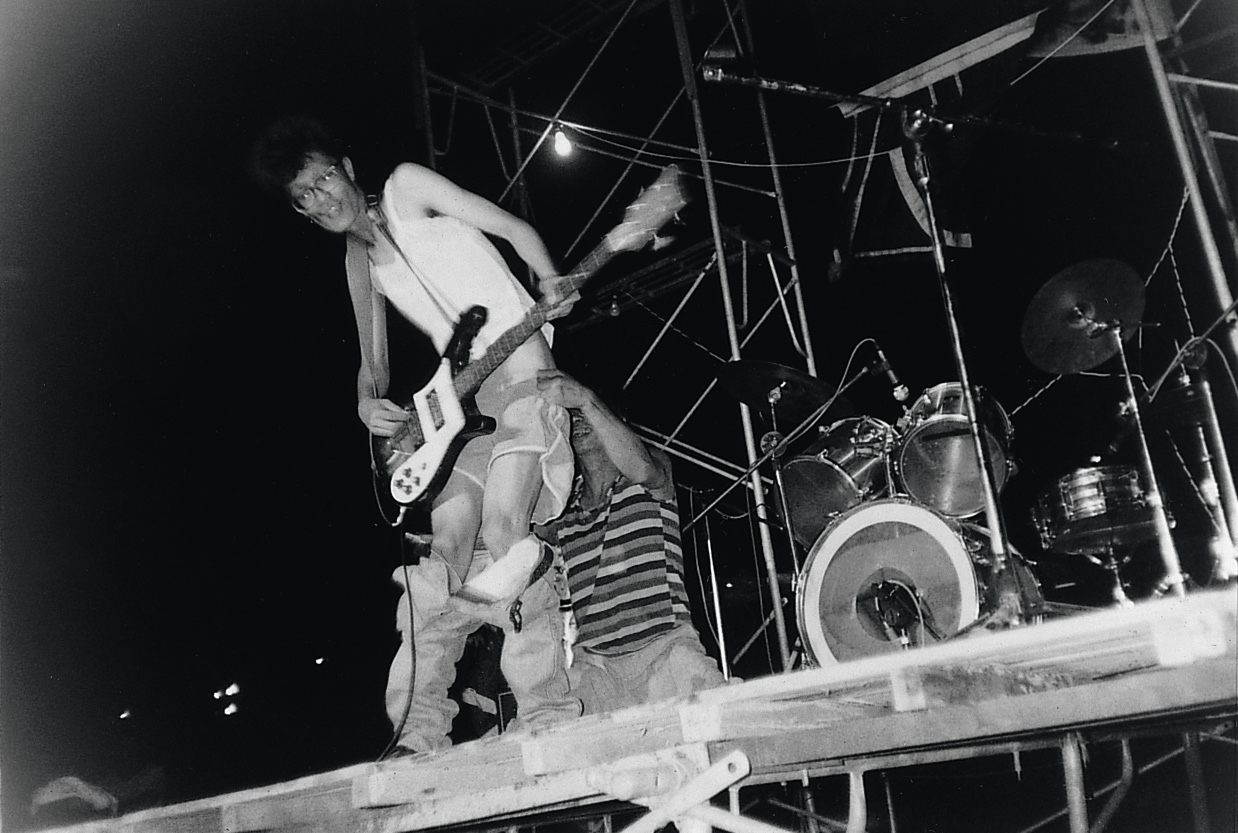

Lin Chi-Wei is a prominent member of the pioneering generation of Taiwanese noise/sound artists that sprang into action in the 1990s. Although originating among young students and artists in an underground (or at least alternative) scene in Taipei, these artists seem to have had broader ambitions from the beginning — and something of an eye for posterity. Work was documented in recordings (for example, those released on Wang Fujui’s Noise label starting in 1993) and on film (most famously in Huang Ming-Chuan’s performance documentaries of 1995). [1] Recently, these documentary materials have formed the basis of several important exhibitions; what was once alternative has, inevitably, become institutionalized, and the work has followed a direct trajectory from abandoned industrial buildings to the museum. [2] Lin chalked up landmark contributions during this initial period, as an independent performer and artist, as a member of the collective Z.S.L.O. (Zero and Sound Liberation Organization), and as an organizer of the riotous Taipei International Post-Industrial Arts Festival (1995).

Alistair Noble: The 1995 festival was quite sensational, and I notice that everyone writing about you uses it to introduce your work. How do you feel about that?

Lin Chi-Wei: Yes, this is part of my work, very true, and much more influential than any of my ‘artwork’. But I am just one worker at the festival; I am not even the main organizer.

Histories are important. In the case of Lin Chi-Wei, they help us to hear the trajectory of his thoughts and works over time, yet they also cast shadows that obscure some aspects of the work. This is especially true of artists whose past is connected with stories that have taken on attributes of myth, as is somewhat the case for the 90s generation of noise artists in Taiwan. Adding to the complexity, Lin is an artist who has worked across a wide range of media in writing, video, installations, and as a curator. In 2016, he will present an exhibition of recent painting and collage work in Hong Kong before returning to music composition with a planned new CD album. Alongside these varied projects, there will be further performances of pieces like Tape Music (of which, more later) in Asia and Europe. This array of artistic output in so many forms does make Lin’s work as a whole difficult to analyze — but sound has been a vital concern throughout his career. Examination of this aspect of his work that inhabits the marginal spaces between noise, art, and music serves as a good starting point.

AN: How do you feel about the various labels we use for audio-based art (e.g., music, sound art, noise, etc.)? Do you think of your work in relation to such things?

LCW: I actually wrote a book (Beyond Sound Art: The Avant-Garde, Sound Machines, and the Modernity of Hearing) [3] on this issue, which is 600,000 words and took me nine years to finish. Certainly, I am against the way all these vocabularies are used today. My artwork is nothing but an attempt to break these genres, not because I intended to do that, but naturally, sounds are free from the genres. I know that some people say to themselves, ‘Ok, let’s do some sound art’, and it is nothing but an effort to fulfill the needs of culture norms. Yet, if they are creative, there will always be something that escapes from the definition of genres; also, as you may know, in the context of Chinese culture, 聲 (sheng) and 音 (yin) could mean something totally different [4]. That’s another story.

Politics

As with everything in 1990s Taiwan, this noise movement was seen to be mixed up with politics — indeed, the radical arts festivals of 1995 coincided with the lead-up to the first democratic presidential election. Taiwanese politics is, like politics generally, simple at first glance but complicated under the surface. This complexity is supercharged by the special history of Taiwan and, while the outward appearance (especially in terms of mainstream and international media) is dominated by the relationship with China (which is itself by no means a simple binary), there is an inward-facing politics that is concerned with the negotiation and expression of identities in a multi-ethnic, multi-lingual island. The crucial thing about the 1990s, arguably, was that with the end of martial law and the shift toward a more democratic administration, it became possible to say things that were previously unsayable, to make noises that were previously unhearable. This is not to say, however, that the expression of noise art is by default associated with mainstream institutional democracy. Even though both arise from the exploration of related freedoms, there is not necessarily a direct correlation. [5]

AN: I’ve read that you were critical of the student organizations in Taiwan in the 90s. I wonder if you could explain that? Is this in relation to the White Lily movement?

LCW: Not critical at all; I was kind of an outsider then.

AN: I was in Taipei during the Sunflower student demonstrations in 2014. [6] An interesting time. Do you have any thoughts on this and the contemporary situation in Taiwan, especially in relation to art?

LCW: The movement is weak, just as the art world is today. I like 賤民解放區 (Jianmin Liberation Zone), by the way. [7]

Listening and Time

With some kinds of music, John Cage once said, "all you can do is suddenly listen, in the same way, that when you catch cold, all you can do is suddenly sneeze". [8] Yet we run into a problem here, with Lin’s work, in that much of it is inextricable from an event, a particular performance in a particular place with particular people. And while there are recordings and video documentation of many such events, these serve to remind us of the distance in time and place between us (the listener/observer) and the original participants, whose first-hand experience of the work is irrecoverable.

AN: In many ways, your more recent work seems more subtle, more gentle, but maybe that is an illusion? How much of the 1995 aesthetic is still part of what you do, and what has changed since then in your work?

LCW: I consider my work to be a way of communication, so you must see who you are talking to and where the conversation is going, that’s all. It is meaningless continuously doing the same thing, for the audience today is extremely different from the 90s audience. But I wonder as well... maybe I haven't progressed a lot in what I want to say since then.

AN: I noticed that you have lived for some time in Beijing, and of course you’ve had many performances in China. How does that feel for a Taiwanese artist, in terms of identity and politics? Does it have any effect on your work?

LCW: Big question. Yes, facing different audiences obligates me to do different performances, as I tend to improvise a bit according to the context. For example, body provocation is not so provocative for a Beijing audience, but sexual politics is highly sensitive there!

The post-1968 ‘turn to the event’ in French critical theory [9] is not unrelated to the earlier turn in art practice from emphasizing works to highlighting events — Cage was a key player in this, but was acting consciously as part of a tradition reaching back to the Dadaists of the early 20th century. The noise performances in alternative cafes of Taipei in the 1990s and the Post-Industrial Arts Festival co-organized by Lin in 1995 arose partly from local concerns and conditions but at the same time form part of this far-reaching tradition of radical performance-based art. Lin himself has traced key aspects of this lineage of creative thinking in his book, Beyond Sound Art, and the emphasis on the performed event over the commercially reproduced work has been a key aspect of Lin’s art throughout his life (despite his prolific artistic output, he has so far made only one album-format CD).

The Machine of Voices

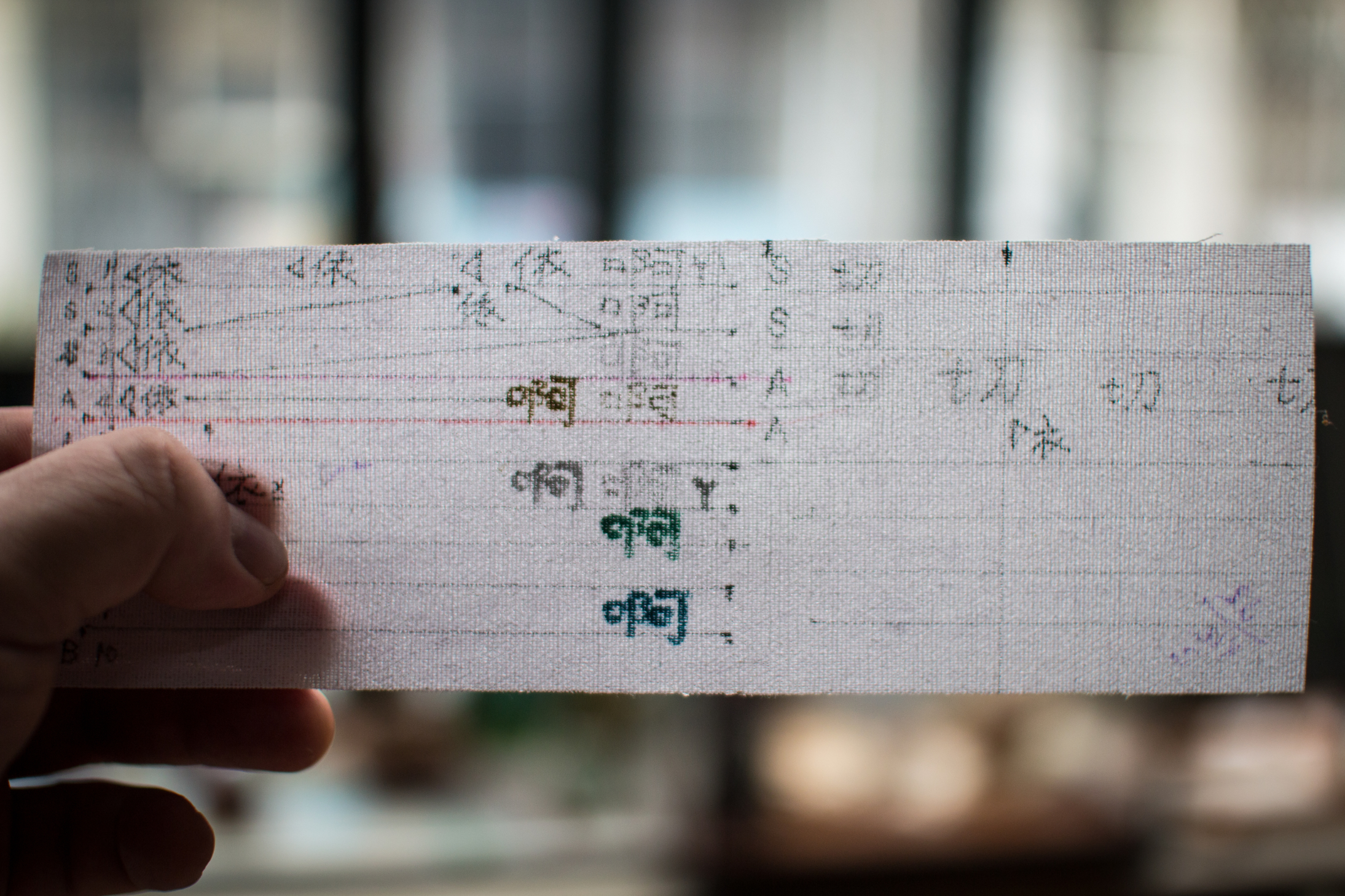

The most widely performed of Lin’s recent works is the series best known as Tape Music (2004–present). The composer’s website lists more than 40 performances of several variants of this piece in many countries around the world, under a variety of titles (for example, a multi-track version of Tape Music performed in Taipei in 2014 was titled "Etude Seven Tones"). The essential form of the work consists of a long ‘tape’ of ribbon or paper (varying between 50 and 150 meters in length) on which Chinese characters have been hand-printed or embroidered (there are versions of the piece in both traditional and simplified characters, and also in some European languages). [10]

AN: When you compose the Roman-text versions of Tape Music or prepare them for non-Chinese audiences, is there still any use of tones (as with the Chinese version) in the composition?

LCW: No, so the variation between eu, a, aa, e, o, or, oo, i, ee, u, uu, ü (etc, depending on which language is used locally) turns out to be critical. I always do a local language version if time permits (thus far, Mandarin, Cantonese, French, Swedish, English, Indian, Thai and Taiwanese versions have been made).

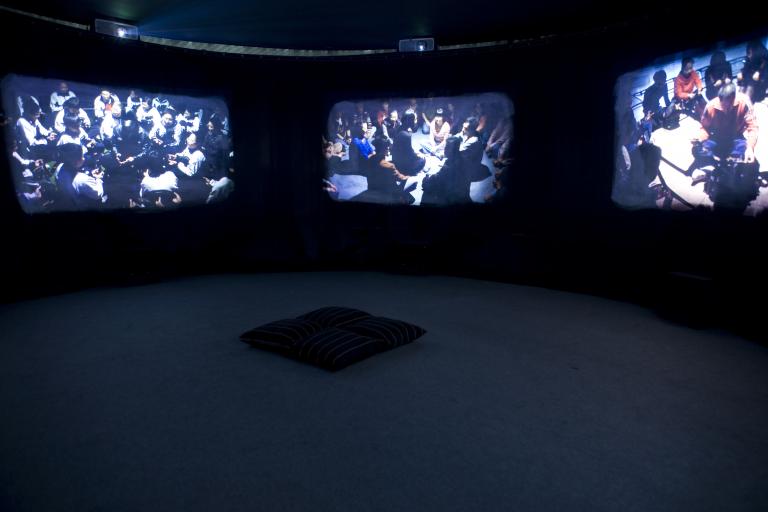

Over time, Lin has developed a set of rules for the performance of this work, which govern the behaviour and actions of participants, including the artist and an assistant, as well as the documentation of the performance (which is thus drawn into being a part of the work itself). Radically, the one aspect of the work that is not determined by any rule is what the participants should do in making sounds — the tape is simply passed into the audience by the artist "without giving any previous instruction". [11]

The tape is then looped around the room, from hand to hand, as it is unrolled by the artist seated at the center. Miraculously, audiences seem to understand without explicit explanation that they are invited (or obliged) to realize the words on the tape through speaking or singing. Once this initial uncertainty has passed, the work unfolds as a powerful example of a machine piece; the audience becomes a multi-headed tape machine simply playing the tape created by the artist. Sounds, tempo, timings, duration, rhythms, repetitions, and pauses are all controlled (to varying extents) by the data pre-recorded on the tape.

AN: I’m very interested in the rules for performing the Tape Pieces. Do you also have a system for making the tape (choosing the words, etc.)?

LCW: Yes, as you can see, the tape music is a tape-delay machine (which was popular in the 70s); in this way, it can build a sound mass via the combination of small sample pieces. As for the choosing of Chinese characters, as you may know, there are four tones in Mandarin, which fit together to build natural harmonics by simply combining them. For example, 衣 and 乙 together form a perfect small third, etc. The theory was developed by linguist Liu Fu in 1924 in his famous book Record of Experiments on the Four Tones《四聲實驗錄》 if you are interested.

Also, I explore the Taiwanese language in order to revive the ancient seven-tone system of medieval Chinese. [12] Today, Mandarin has only four tones, which is, according to the Eastern tantric Buddhist school, lacking the winter/north or killing tone (Rù tone 入聲), which has the strongest dynamic and shortest duration of the seven. I find it really critical for today’s sound/music composition. As for the Roman version, I have a diagram as the basis of my composition. Please consider it a pyramid with ‘I’ at the top, but I think basically it is just my personal superstition.

AN: Why is the symbolism of this Rù tone in Taiwanese so important for your work?

LCW: Actually, I think it is an essential cultural issue concerning the sound. The lack of the Rù tone in Mandarin (國語), musical composition, and poetry actually means the absence of a powerful dynamic in sound expression. To give a famous example, in the Tang dynasty poem by Liu Zongyuan, "River Snow" ( 江雪), if you read it in Taiwanese or ancient Chinese, all sentences end in the Rù tone. It sounds very brief, almost like pressing the brake hard, which corresponds to the feeling of extreme coldness in the poem... this is sublime. Also, I believe that the absence of the Rù tone can be a symbol of the collective unconscious, of ignoring the dark side of real life, a real culture crisis.

The Children Laugh

An untitled track from the 2008 Sub Rosa release An Anthology of Chinese Experimental Music 1992-2008, under the name "Eric Lin", begins as an abstract composition for voice. [13] From a rich assemblage of vocalized sounds, syllables, and sung notes, the piece coalesces into a simple, steady beat with melismatic soprano melodic lines soaring above, like medieval cathedral music. At the close, these melodic lines scatter and disperse, leaving only the fading ostinato pulse with the sounds of playing, laughing children rising to the surface to ensure that we appreciate that the material of the work derives in some way from a live performance with children present.

Feeling like a document of an event as much as an album track, this beautiful work leaves one wondering how it was made: What were the controlling instructions that brought this into being? Is there a score of some kind? Is it one of the Tape Music pieces? With characteristic fluidity of labeling and framing (even of himself), Lin obscures much of the work’s original nature, in this instance leaving us with just the sounds and our imagination. In fact, this work is made from recordings of live performances of Tape Music. In the repackaging (dare I say, reterritorialization) of this material for CD release, some aspects of the original performance events are lost, but others are gained.

Hardware & Software

Several of Lin’s works have used instruments rather than computers or voices, but always in unconventional ways and within the frame of interesting systems of rules. He also has a long-standing interest in the use of instruments played by non-experts, often making use of amateurs in the audience. In "Balloon Music" (China Avant-Garde Music Festival, Beijing, 2009), instruments such as drums, bells, and toy trumpets were floated around the stage suspended by strings from balloons. The performers on stage, after playing for a while, were instructed to push the instrument-carrying balloons towards the audience, thus obliging the observers to participate.

"Balloon Music" plays with experimental notions of chance versus control — while the movement of balloons across the room is not entirely random but determined by performers pushing them in certain directions, we may also say that this is somewhat out of the direct control of the composer. The initial setting up of the performance, then, is like a machine or a computer program which is then set to run with broadly predictable results, within which many unplanned events take place. We must also consider the element of obligation, the hint of subtle coercion in bringing the audience into the performance. Here also, the composer’s will is exerted through the design of the machine program. The performers’ choices are seemingly free but also carefully limited to a narrow range of options.

AN: A lot of your work seems to be playing with the relationship between control and non-control, for example, some aspects of the human-machine are controlled by rules (or the tape) and other aspects freer.

LCW: Yes!

"Cellular Automata Music" (2007) is even more explicitly operating as a kind of program, running on a machine-computer built of humans with instruments. Here, performers were each given a set of instruments, a specific seating plan, and a set of rules about which instruments to play and when. Some of the decisions must be made according to the behaviour of other performers sitting adjacent. Interestingly, this work was first performed in a version called “beta 0.7.1” (Taipei MOCA, 31 Oct. 2007). After subsequent analysis and critique through discussion with the audience, the work was revised with "bug fixes".

Later performances were given as versions "0.7.2" and "0.7.3" [14]. Judging from the currently available recording (of "0.7.1"), this is a sonically wonderful piece. The effect must be even more powerful for those experiencing the event in person, where one may experience the sounds in their natural space and see the machine at work. Listening to it, rather than thinking of the immediate inspirations in game theory and machine code, I am aware of an affinity with the more experimental works of José Maceda (for example, "Ugnayan", a 20-channel radiophonic piece from 1974).

In some respects, this is one of Lin’s most regulated and controlled works, and the result does have aural integrity and strength. One is reminded of Richard Schechner’s dictum, to the effect that the more freedom performers are allowed, the more conservative will be the artistic result, and vice versa. [15] Much of Lin’s work might be understood as experimental testing of such a proposition. A great deal of contemporary art that is branded as ‘experimental’ is, in fact, not only deeply conservative (tightly bound to the demands of the global art industry) but also not actually experimenting in any meaningful way. There is a refreshing clarity in Lin’s approach to experimentation through art, and "Cellular Automata Music" serves as an exemplary model, incorporating beta trial versions of the work, critical feedback, revisions, and re-performance.

Erotic Journeys

Alongside Lin’s long-term interest in human voices and the operations of human machines, he has also produced works through laptop performance and computer-oriented studio work. His largest work in this latter field is the album Erotische Reise nach Westen (2003). [16] This was produced at Le Fresnoy Studio National des Arts Contemporains in France and is a complex work made with recorded sounds and computer-generated materials. In some ways, this offers a useful key to Lin’s artistic thinking, from a musical perspective, for we find here even in the studio his particular combination of seriousness of purpose with ironic humour; of sounds both created and found; of the beautiful and also the destabilization of beauty; and sometimes a little madness (as when the automated tremolo in the track "Klassistische Muzik" become black-midi fast and strange morse code signals seem to be a byproduct of the tripping computer’s effort). In this album, we can hear Lin playing the studio apparatus as his art-making machine and exploring aspects of the human/machine relationship that haunt his work generally. The inclusion of ‘real world’ sounds (doors opening and closing) and conversational voices (like the laughing children and audience noises in other works) suggest a permeable quality to the overall controlled environment; the studio walls are allowed to breathe just a little.

The album's title reminds us of another thread that runs through all of Lin’s work: the interrogation of embodiment, physicality, and sensuality. This manifests in a wide range of forms, from the grotesque splattering of bodily fluids in the Z.S.L.O performance at Taipei International Post-Industrial Arts Festival to the more elegant but equally intense demands made of participants in Tape Music. In Erotische Reise nach Westen, we hear something perhaps even more intimate: Lin’s own direct engagement with the physicality of sound, his own ears at work in the studio.

AN: I enjoy very much your album Erotische Reise nach Westen. I’d be interested to know more about how you made it. Also, how do you feel this work relates to your performance work outside of the studio (e.g., the Tape Music pieces)?

LCW: Erotische Reise nach Westen is basically musique concrète, using the same methodology as Pierre Henry... probably more than that of Schaeffer. Tape Music, yes, totally. It’s nothing but how to make sound synthesis by working with human beings.

The Choir of Amateurs

AN: The Z.S.L.O. track called "422189". Is that a piece you were involved in making?

LCW: Yes, basically, it was a cooperation between Lili Liu (Singing Liu) and me. It is actually also musique concrète, even though it doesn’t really sound like that. Everything was made with extremely simple materials, which you may not believe. We worked with 1950s technology, which means that not even a synthesizer, sampler, or sequencer was used. We had a microphone, a delay effect, and a function generator (used industrial), and everything was recorded and mixed to a 1/2-inch Fostex 8-track recorder, that’s all. A huge amount of time was spent on the composition, which would seem ridiculous these days; however, I like the very corporeal sensation of the result. Certain parts of the piece make people feel the need to go to the toilet.

The track titled "422189", made by Z.S.L.O. in 1998 (the title seems to be made from the date, Christmas Eve), begins with a man’s voice counting in, "1, 2, 3, 4". The counting gets faster through these four beats, so the aspect of a controlled beginning undermines itself from the start — or even before the start. Over folksy guitar strumming, cacophonies of multi-tracked voices sing what seems to be a variety of songs and vocalize simultaneously, like an insane choir. The juxtaposition of such seemingly unrelated objects has at the first impact a random, improvisatory quality, but on closer listening, one starts to hear relationships between the constituent elements. These relationships may be accidental or planned — or a bit of both — but they are nonetheless real in the listener’s perception (and through the surface chaos and improvisation, one can easily hear that there was some kind of plan to this piece, however unconventional, controlling and framing the sounds).

A key part of this work is the deliberately rough, amateurish feel — with miscounting, simple guitar-playing, chaotic singing. But the clumsiness is a knowing clumsiness, and there is weird, passionate energy behind the work that takes it far beyond facile messing about. In the original sense of the word (one who loves), the true amateur has a great artistic force that is often underestimated.

Escaping Constraint

In the slow, painstaking creating of a piece like "422189", from the basic ingredients of collaboration, voice, analog delay, and multi-track tape, we may finally trace clear trajectories of material investigation and creative thought from Lin’s present work (in Tape Music, for example) all the way back to the early years of his career. Even the somewhat brutal, violent spectacles of the Taipei International Post-Industrial Arts Festival might be analyzed as parts of an elaborate machine-work: a complex program of materials (including people) operating within rules and frames, with varied and sometimes extreme, possibly unexpected, outcomes. Set it up, switch it on, and see what happens.

Repetition and the delay-effect are almost constant preoccupations in Lin’s work, as are the sound-generators of (untrained) voices and the deliberately amateurish playing of things like drums, guitars, or toy trumpets. Humans, as much as technological objects, are his instruments, the hardware upon which his art operates like a software program — and in this, there is an interesting, sometimes uncomfortable play of power that we may analyze in sound as the interplay of frames of control deployed over the sound-generators, within which they have only limited aspects of freedom. Here, we encounter the darker side of Lin’s work, expressed in subtexts of violence, the provocative consideration of danger, of obligation, and anxiety. Here also is the crucial symbolism, both esoteric and practical, of the disruptive ‘entering tone’ Rù (or, as Lin calls it, the ‘killing tone’) — the harsh winter approaching from the north, a struggle against the amnesia of our chaotic present.

Tying all this together is Lin’s concern with communication, and in this regard, we might observe that even at their most abstract, his fragmented and layered voices carry a message that transcends simple words. As the sound theorist Trevor Wishart has observed, the very sound of language carries its own inherent meanings, even when we can’t understand the language. [17] Meanwhile, the words we use to describe various genres and categories of sound-based art are often awkward; but in Lin’s work, we find that there is noise, sound (varying degrees of abstraction), and art and performance-event. And there is also, both despite and because of all this, music.

1. Huang Ming-Chuan, 1995 Taipei International Post-Industrial Arts Festival [Documentary Film, 1995] (DVD, Formosa Filmedia Co.), and Resurgence on the Tamsui River [Documentary Film, 1995].

2. For example, Lurking Waves: Fujui Wang / Collected Objects from the 90s at The Cube, Taipei (2013) & works by various artists included in ALTERing NATIVism – Sound Cultures in Post-War Taiwan, Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts (2014) et al.

3. Lin Chi-Wei,《超越聲音藝術:前衛主義、聲 音機器、聽覺現代性》(Beyond Sound Art: The Avant-Garde, Sound Machines, and the Modernity of Hearing) [in traditional Chinese] (artist published, 2012).

4. 聲 shēng and 音 yīn are both commonly translated into English as ‘sound’, although the former has connotations of the voice, while the latter tends toward sound as abstract tone. The two characters are often used together, as a generic term for sound, as in 聲音藝術 shēngyīn yìshù (sound art).

5. Yu Wei, ‘Lin Chi-Wei: noise and invocation’ in Leap: the international art magazine of contemporary China (Oct. 2012), 143.

6. The Sun Flower Movement was started in 2014 by students to oppose the Cross-Strait Service Trade Pact, a treaty between Taiwan and China.

7. 賤民解放區 (Untouchable Liberated Area) was a project of a splinter group breaking away from the main organization of the ‘Sunflower’ movement as a protest against the perceived undemocratic nature of the larger organization. Information about the group and their manifesto may be found on their Facebook page (in traditional Chinese).

8. John Cage, ‘Composition as Process’ in Silence (Wesleyan University Press, 1961), 46.

9. See Razmig Keucheyan, The Left Hemisphere: mapping critical theory today. (Verso, 2013), especially the discussion in chapter 5.

10. For a documentary video of one interesting performance, see Tape Music for Beijing Shout it Loud Festival (2007, https://youtu.be/ IZ30qylt8kI).

11. Detailed information is given on the artist’s website (http://www.linchiwei.com/ archives/410).

12. The Taiwanese language has 8 theoretical tones (聲 shēng), of which 7 are discernible in practice. There are yīn and yáng forms of the Ru 入 tone (陰入 & 陽入, corresponding to high and low pitch), usually classified as tones 4 & 8. In terms of phonetics, both are checked or stopped sounds or, as a musician might say, somewhat percussive. The Ru tone is usually called the ‘entering tone’ – Lin’s use of the term ‘killing tone’ refers to a Chinese Buddhist tradition of śabda-vidyā (聲明學), an ancient science of language. For more information about this language-symbolism, see 王昆吾 & 何劍平 編著,《漢文佛經中的音樂史料》(Bashu Publishing House, 2002). Chinese] (artist published, 2012).

13. Eric Lin, [untitled] on An Anthology of Chinese Experimental Music 1992-2008 (Sub Rosa).

14. http://www.linchiwei.com/archives/556

15. Richard Schechner, Performance Theory (London: Routledge, 2005), 17–18. Originally published as Essays on Performance Theory (Ralph Pine, 1977).

16. The title of the album refers to the famous Ming dynasty novel《l 西遊記》 (Journey to the West) attributed to Wu Cheng-en (吳承恩)

17. ‘The language stream itself conveys meaning in many ways (in many different sonic dimensions...)’. See Trevor Wishart, On Sonic Art. (Harwood Academic Publishers, 1996), 299.