Water is about eight times denser than air (similar in density to your inner ear fluids and the rest of your body’s tissues). This difference in density means that water has a higher impedance than air — it takes more energy to start a sound underwater, but once it gets moving, it travels about five times faster, confusing everything from our ability to identify sounds to our understanding of where they are coming from. (1)

In the spring of 2011, South Korean artist Daeil Lee asked me to meet him at one of the public outdoor bathing pools beside the Han River. He was testing equipment before his first underwater concert event, and I wasn’t sure what to expect. I recall that when I jumped in, I was surprised at the clarity of the underwater sound experience. But I recognized that it had some curious qualities about it, such as that it seemed difficult to locate where the sound was coming from. Then, to break the surface for breath was to suddenly exit the audio field as the sound could not be heard when your ears were above the water. To bob in the water was to toggle between two somewhat separate acoustic worlds.

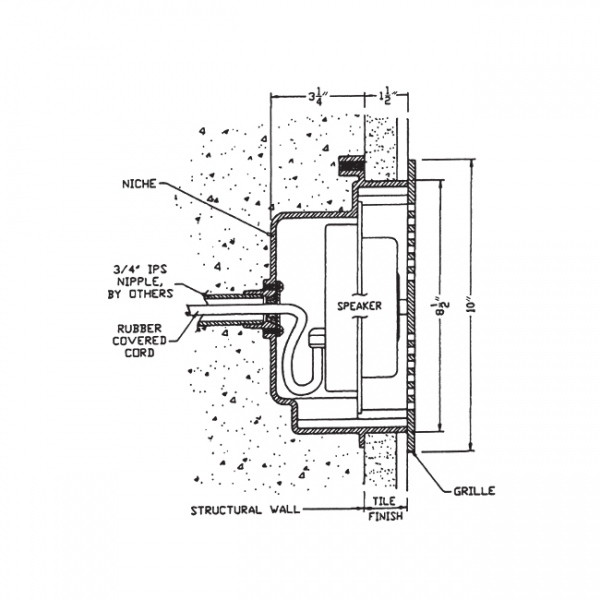

On the floor of the pool were two flat-faced discs. Upon touching them, their whole surface was vibrating. The guy looking after the pool had agreed to allow us to hold the event there. However, during our test visit, the facility owner arrived and became irate about his pool being used for such a crazy activity. We were out on our ear, with Daeil being forced to continue searching for a supportive venue.

Posters on the Seoul subway advertised pool party events with images of beautiful microphone-clutching youths being propelled, laughing, by swirling jets of sunlit water. But it was the height of an odd summer that had seen almost seven weeks of grey skies and continuous rains, sometimes downpours so heavy it was like we were under a crashing fury of waves.

Finally, the weather broke, a new venue was arranged, and the underwater concert went ahead.

Ian-John Hutchinson: You did a concert series called 'Underwater Concert'. What was it?

Daeil Lee: I invited guests to come to the pool and listen to the sound with their ears submerged. Nothing could be heard outside the water. That is why it is called the "Underwater Concert". A pair of underwater speakers were used.

I-J H: When did you first get the idea for the series?

DL: The very first moment that a human being perceives the world must have been through sound. I wanted to create a circumstance where the sound can be heard in a womb-like medium.

I-J H: How many concerts have there been so far? Where?

DL: The first one was in 2011. It was at an outdoor pool in Seoul. And the second one was this year at a sports center pool in Matsudo city, Japan.

I-J H: What was played at the concerts? Who contributed sounds? Which contributions were most interesting to you?

DL: At the first one, sound pieces of 10 artists were played. They were sound artists from Paris, New Zealand, and Japan. I asked them to compose a new sound piece or to send me appropriate sound works for the theme "Water-distant memory". And I mixed my heartbeat, and deep breathing sounds to them and mastered a 60-minute loop. Interesting ones were: water dripping sounds by Tomoko Sauvage (sounds recorded using hydrophones) and people mimicking the sounds of sea mammals by Ian-John Hutchinson.

I-J H: What problems and difficulties did you have when putting on this series?

DL: Female guests are not always willing to jump into the pool. Breathing correctly to listen to the underwater sound long enough is a bit tricky as well. But the most difficult part is to explain to people the exact reason I do this unusual concert at an unusual venue.

I-J H: What feedback did you get from concert guests? How did people respond?

DL: Last November, when I did my second one in Japan, I just put a small notice on the wall of the pool saying, “You can hear something underwater today”.

After the regular swimming guests recognized my sound piece, while they were swimming, they were quite pleased. Someone told me it was relaxing and funny.

I-J H: Has this concert series influenced your other work?

DL: It certainly was a great chance to experiment with a new way of sound art. I will continue to do further projects in diverse underwater situations.

Concert guest, artist Ghim Taedeog: It was my second experience with Daeil's underwater concerts. With the first one, I actually was standing outside and just dipped my face into the water and listened to the sound resonating underwater. Of course, the first experience was quite interesting. The sound delivered through water sounded totally different from the sound radiating in the air. I participated in his underwater concert while I was in Tokyo for a P_AIR program. Then I decided to experience his work fully, so I changed into a bathing suit and went into the pool… The first experience also was very interesting, but I realized that I just tasted half of the concert. The second one was really shocking. That was a sound that you can hear not only with your ears but also with your body. As I got closer to the speaker, I could even feel the sound waves in my body. I kept wandering around the speaker, listening to and feeling his concert. I was there for more than an hour without realizing that I was in the water for so long.

I-J H: This statement by a concert guest made several months after the event places emphasis, quite rightly, on the physical power of underwater sound and the sensations of immersion in the water, which are outstanding features of the event.

The potential poetic density of the underwater sound space is also very rich. Daeil’s idea about how the context and the content would reinforce each other was through his interest in the notion of prenatal listening. Contributing French artist Emmanuel Rebus thought to introduce the audible character of solid structures into a fluid medium as a curious listening experience from both a technical perspective and a poetic one.

“I have to say that I have never heard an underwater concert in my life. I sent Daeil recordings made in big metallic structures (pillars, 'wind shields'), where the speed of sound is quicker than in air, just like in water.”

Where liquid is denser than gas, solids are denser again (except ice, a solid that is structurally expanded and therefore uniquely floats upon its own liquid state). The work of Tomoko Miyata (Tomoko Sauvage) was medium-matched, as she uses hydrophones to record percussive noises and tones from underwater, the relationship of wave action to the boundary. In my own piece medium, species and environmental translations took place. In the months before the event, I asked volunteers to listen to recordings of flora and fauna of underwater Antarctica and then recorded them exploring and mimicking the sounds of that distant world with their own voices. These examples, just a few from the first event in Seoul, indicate the genius of the underwater concert concept, as it plays into an element that is intimately bound up with listening, that of water.

As I write this, a pot of water boils in the next room, and I imagine listening to it in the pool.

There is a lot of variation in the amount of time people want to spend in a pool. An hour-long mix was made from the various works, the result being that most guests couldn’t attend to the whole thing from start to finish as they might attempt to do at a seated concert. And, of course, one always had to break the surface to breathe. The pool itself is a principle of movement and of play, and the idea that guests would be cutting and splicing between over and underworlds (and cutting between attention and inattention), and on top of that, continually changing position relative to the speakers, made for an interesting dynamic to how the sound was heard.

Sound itself emphasizes the intensity of territory in its frequent disrespect of boundaries (going around them or through them) and its insistence that the body or other surface vibrate and propagate the signal. In this regard, the watery context is even more intense as a sound-filled space. The signal wave has more power in the water and is capable of traveling over long distances. In the water, our bodies are supported, buoyed up, and moved by wave motion. In the water, we relinquish some control over our position and the determination of our personal space. Interestingly, to date, this event has been held twice in two different parts of East Asia, a region where there are ongoing international disputes over sea borders and maritime zones of exclusive interest and where disputes frequently lead to serious incidents.

Pushing itself as what it is, a chance to have a good time, the underwater concert series is also proving to be a forum where contributors and guests stand to learn a great deal, a forum whose potential seems yet far from exhausted.

1) The universal sense: How hearing shapes the mind, Seth Horowitz, Bloomsbury,2012.